All Things Affect Each Other

Sal Randolph talks about language, action, and connection

KARAN

Sal, your poems feel as if they’re written from the threshold between matter and spirit, language and sensation, philosophy and flesh. “Trans Rilke” reanimates Rilke’s Duino Elegies through a queer, ecstatic, urban voice. I’ve been reading Rilke recently and I love how your tribute is both a homage and an undoing. Let’s start there: what drew you to Rilke, and what did it mean for you to trans him — linguistically, bodily, spiritually?

SAL

Those Rilke poems found me when I was nineteen or twenty. I had a passionate and dramatic imagination in those days, so I had a passionate encounter with Rilke. I didn’t read the Duino Elegies academically, but I did study them in the way you study a person when you’re falling in love. How could those poems have occurred in him, happened to him?

We all have lines of poetry that somehow become part of our body, perhaps our body of language. Those lines of Rilke are like that for me, and they often rise up, especially when I’m thinking of things like beauty or poetry.

At the time I wrote “Trans Rilke,” I was working on a book about beauty. I could never find the language I wanted for that project, so it didn’t get written, but during that time I was trying to understand what beauty was (impossible). I see in my notebook that I was also reading Sara Ahmed on queer use, particularly the queer use of language.

I didn’t set out to queer or trans Rilke, it’s more like his poems became part of a storm of language and ideas that queered or transed me as I wrote them down.

KARAN

Across these poems there’s a fascination with permeability — the self as fluid, as exchange. “Each wave destroys the next,” you write, “and are we like this, destroying ourselves?” It’s one of many moments where you seem to question the possibility of wholeness. What does it mean to you to live (and write) inside that kind of dissolving?

SAL

I’ve been a Zen student for many years. The Buddhist word for the kind of dissolving you mention is shunyata, or emptiness. This emptiness doesn’t imply an absence of things or of form, but rather a boundarylessness. All things interpenetrate and affect each other — the “thingness” of things is a feature of our conceptual minds rather than the world. Which is to say, I think all of us are living inside the kind of dissolving you refer to, because it’s a fundamental aspect of reality.

I was also looking at waves when I wrote that poem, choppy wavelets. They reminded me of an image by the artist Vija Celmins. For decades she made drawings, paintings and prints from a single photograph of waves which she had taken off the Santa Monica pier in the late 60s. Each image in the series is “the same” but it’s also different. The sharp little wavelets are separate and distinct, but also inevitably part of a whole, which in this case is the field of the image, but also the ocean.

KARAN

I love how the poems enact a kind of thinking that’s deeply sensual. In “A Future,” erotic memory becomes almost philosophical: desire as an archive, as a way of measuring what’s been lost. What’s the relationship, for you, between eros and intellect, or between pleasure and knowledge?

SAL

I think pleasure is its own form of knowledge, as is desire. Further, as a reader, I prefer it when the intellect is embodied, which is one reason I love poetry.

That poem, that future, was part memory and part fantasy. Among the things I do miss in the current era is the ubiquity of ordinary pubic hair.

KARAN

You’ve described yourself as working “between language and action.” These poems, especially “Into the Waters,” seem to move that line. How do you see your work in poetry relating to your work as an artist? Do the two share a metabolism, or does each require its own kind of attention?

SAL

I began as a poet and moved towards art as a way of finding more immediate interaction and direct connection. Most of my art practice was social and participatory.

One of the early projects I did was an artist's book called Free Words. It was hot-pink, and on the back it said “This book belongs to anyone who finds it.” I freed the contents into the public domain and infiltrated copies of the book into as many bookstores and libraries as I could. Eventually many people around the world helped me do this.

Right before I started that project I had been spending a lot of time writing in libraries. Whenever I was stuck or needed a break I wandered the shelves. I developed a persistent fantasy that I would find a book that was left there just for me. Free Words was an attempt to make such a book. It was also an attempt to create a situation: the person who found it would have to decide whether to take it or not, and how to go about carrying it out of the store.

I wanted the content, the text, to seem both open and specific so that anyone might feel a connection. This was a bit of a puzzle. In the end, the text was a word list I had been accumulating for a decade as part of my writing practice. It was never intended to be read, which gave it the kind of unselfconsciousness and permeability that I was looking for.

Much later I got an MFA in Public Action. The work that I made during that period included an immersive installation in which people lay down and listened to a long poem/meditation I wrote about slowness and rivers. Another project was an extended essay on publishing as a form of public action. Language has been entwined with all of my art practice.

KARAN

There’s also something oceanic in your work. We see literal and psychic water everywhere: tides, floods, veils, dissolutions. “We look down into the waters and everything is in constant motion.” What draws you to water?

SAL

I’ve always lived near the water. I was born in New York, but moved to Hawaii when I was nine and lived there until I left for college.

I think my strongest early aesthetic experiences were of sky and water, especially the horizon line of the ocean. Sky and water appear in my writing all the time. And I love monochromes, fields, all-over patterns, drones and ambient music. Anything continuous and unbounded.

KARAN

I also dig the rhythm of that poem (“Into the Waters”), and its associative quality of moving from one word to another. How important is rhythm and music to you?

SAL

I’ve been in a couple of bands and making music is a great, deep pleasure, even though I am completely untrained.

Musical feeling is one of the ways language makes itself as I write. It’s like a form of compositional improvisation, not especially conscious but more of an urgency and action of the body.

KARAN

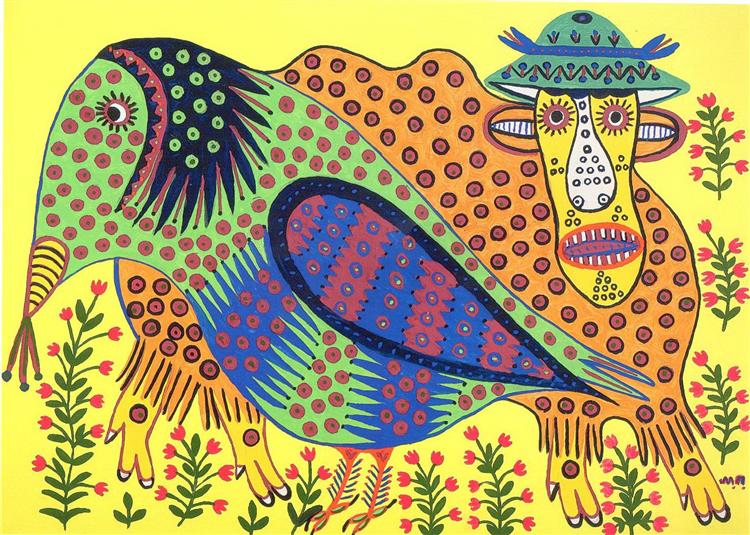

In “The Boat,” the figure of Ada — the boat-bird, the cloven thing — feels mythic and posthuman at once. She’s a creature of transformation, punished by desire, like many of your speakers. What interests you about metamorphosis? And what does it mean, in our current world, to long for transcendence when the body itself is under siege?

SAL

When I was writing “The Boat,” I was thinking of a particular image by the surrealist painter Remedios Varo, Exploration of the Source of the Orinoco River. The painting depicts a woman whose garments are also a boat, one that is steered by a fishlike, pleated fin. The Ada in the poem isn’t in any literal way a depiction of the woman in Varo’s painting, but in some way the dream of the painting became the dream of the poem. I was also reading fables and fairy tales at the time, trying to understand what stories were. I named her Ada, for the palindrome of it, and I suppose I have a special love for those who are neither one thing nor another.

As for the current world, everything I love is under siege, and poetry is one way I feel alive under those conditions. It’s not about transcendence as much as presence.

KARAN

Your work often blurs the moral and the material: “The HVAC system is shuddering and weeping,” you write, “the climate is deteriorating.” That poem, “I Will Go,” feels devotional — environmental grief transfigured into ritual. What role does attention play in your poetry? Do you see writing as an act of repair, or simply witness, or both, somewhere in between?

SAL

I’ve studied attention for a long time, written about it, taught classes on it, and still there’s something fundamental about attention that eludes me. We often think of attention as the ability to concentrate in a narrow and focused way. I’ve come to feel there are many forms of attention, and my affinity is with more mobile and fluid states like reverie.

I was just having a conversation today with another poet about the devotional in poetry. To me the devotional implies poetry that offers itself outside of the transactional world. Devotion is beyond logic and beyond the instrumental. It’s more about a state of being, or a state of love, than it is about outcome. I do think of writing, at its best, as a devotional practice, something to be done from love, and for its own sake.

KARAN

I was struck, too, by “Between Us” that line, “A gift lives between two people and it can die from either end.” It’s such a precise understanding of intimacy and language. What does vulnerability look like in your process? How do you protect, or not protect, what the poem exposes?

SAL

That immediately makes me think of a word coined by the poet Adrienne Rich: protectless. I hope not to protect myself. At the same time, I can’t help protecting myself. Perhaps that tension is part of what keeps poetry and language alive.

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, though the answers are always wildly different: there’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four axes — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. Where would you place your work, if at all? And do you feel it moving elsewhere?ț

SAL

My immediate feeling is that these are all one thing. In Japanese and Chinese, the word for “heart” also means “mind,” and sometimes it might be used in the way we use “soul.” Shin is heart-mind, and a heart-mind can’t exist without a body.

If anything, I might say instead that my affinities are with poetries of language. Many people think of poems as being made of thoughts or feelings, or perhaps images, but I think of them as being made of language.

KARAN

What’s the best piece of writing or art-related advice you’ve ever received — something that’s actually stayed with you, or changed the way you work?

SAL

I went to an artist-run school called Freehand for my poetry education. It was tiny, unaccredited, and took place in the off-season winter months in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Freehand was started by two poets, Olga Broumas and Rita Speicher, with their artist-photographer friend, Marian Roth, as an answer to their frustrations with academic teaching. There were only twelve students, and Olga and Rita both worked as massage therapists to support themselves while they wrote and taught.

Olga’s classes in particular were a revelation. We met in her home every Monday for six-hour long sessions that began with movement, continued by reading poetry aloud for hours, then we wrote and talked. At the end of the day we all learned massage techniques, since poets need some honorable way to make a living.

In the beginning of my second year, I was feeling stuck. Olga suggested a simple exercise: write a page every day for a month and don’t look at what you’ve written until the month has passed.

I remember my lover and I getting up in the morning and taking turns on our shared computer. We were living in a cheap off-season rental on the water, and had a huge window that let in so much sun that some mid-winter days felt like the tropics. We called it the beach. By the end of the month I had work that would go on to win me a fellowship that let us both live in France for several months. So the practice also feels lucky or auspicious!

When I need to start writing after a period of absence or silence, this simple practice is still my foundation. Write every day without judgment or evaluation. Don’t look at what you’re writing. Olga’s definition of “every day” was faithful but not strict: something like five days a week. When I work this way, I try not to pay much attention to what I’m writing. I let myself forget the words almost while I’m typing them. When I do go back and read, I am always surprised.

KARAN

Would you kindly offer our readers a poetry prompt — something strange, simple, or rigorous — to help them begin a new poem?

SAL

For many early years I found it difficult to make words appear on the page, so I developed ways of bringing myself to writing—not so much prompts as instructions, oracles, techniques, games.

One of these was a series of instructions I called “the steeplechase” after the sporting events where horses jump obstacle after obstacle. The first instruction I wrote for the steeplechase was “look up.”

“Look up” can mean look at the ceiling or the sky, it can mean look out the window or at the people or objects around you. It can also mean taking a temporary stance of optimism. The immediate world around you acts as a kind of oracle, or a way of beginning. It’s the most common instruction I give myself and every time I do it, I find something new.

KARAN

Please also recommend a piece of art — a film, a painting, a song (anything other than a poem) — that’s sustained you lately or that you wish everyone could experience.

SAL

I recently re-encountered Keith Jarret’s classic Köln Concert from 1975, a solo piano improvisation. I had it as a vinyl record in my twenties, and would let it play over and over; I find it just as sustaining now. It is a spacious music that permits thinking, daydreaming, reading, writing.

In visual art I often come back to Eva Hesse, especially her No Title, 1970, commonly known as “Rope Piece.” It’s a tangle of knotted strings and ropes which were dipped in latex and hung from the ceiling. When it was first made, the piece was supple and could be reconfigured in different ways. Now the latex has aged and stiffened so Rope Piece lives most of the time in a specially constructed crate that carefully supports its weight. I’ve seen it in person, but it is rarely on view, which is part of what intrigues me. It is at once real and imaginary, a legend, almost a myth.

KARAN

And finally, Sal, since we believe in studying masters’ masters — who are the poets, artists, or thinkers who’ve most shaped your sense of what’s possible in language and art?

SAL

I love to read widely, and my shelves are as full of anthropology, philosophy, and art theory as they are of literature and poetry. This makes your question almost impossible! That said, John Cage, Gertrude Stein, and Frank O’Hara have all stayed close to me over decades. The anthropologist David Graeber was essential to my art practice, and I very much miss him now in our present political moment.

Certainly Olga Broumas, who I mentioned earlier, is a beloved voice. Nightboat re-published her long-out-of-print collaborative work, Sappho’s Gymnasium. Copper Canyon published her collected poems, Rave, along with two volumes of her translations of the Greek Nobel laureate Odysseas Elytis. Many of her lines and of Elytis’s are always in my ears.

As part of my Zen life, I often read and teach Buddhist and Zen poets, beginning with songs written in India at the time of the Buddha, up through China, Japan, the Beats, Asian-American Buddhist writers, the Language Poets, and all their successors and branches. Poetry is everywhere in Zen.

Plus, I always have a rotating group of books in my backpack. I pull three or four from my pile every day. Right now what I’m carrying around includes Will Alexander, Rick Barot, Anne Carson, Édouard Glissant, Fred Moten, Alice Notley, Alejandra Pizarnik, Lisa Robertson, and Rosemarie Waldrop.

There’s also everything that I haven’t read, all the shelves of possibility. Poetry is a big city. It’s important that it’s full of strangers as well as people you’re already in love with.

RECOMMENDATIONS

I recently re-encountered Keith Jarret’s classic Köln Concert from 1975, a solo piano improvisation. I had it as a vinyl record in my twenties, and would let it play over and over; I find it just as sustaining now. It is a spacious music that permits thinking, daydreaming, reading, writing.

In visual art I often come back to Eva Hesse, especially her No Title, 1970, commonly known as “Rope Piece.”

POETRY PROMPT

“Look up” can mean look at the ceiling or the sky, it can mean look out the window or at the people or objects around you. It can also mean taking a temporary stance of optimism. The immediate world around you acts as a kind of oracle, or a way of beginning. It’s the most common instruction I give myself and every time I do it, I find something new.