The Poem Is a Construction Site

About war, form, memory, and the dark ironies beneath beauty in their poetry and the work of of W.H. Auden, Evie Shockley, and others

.png)

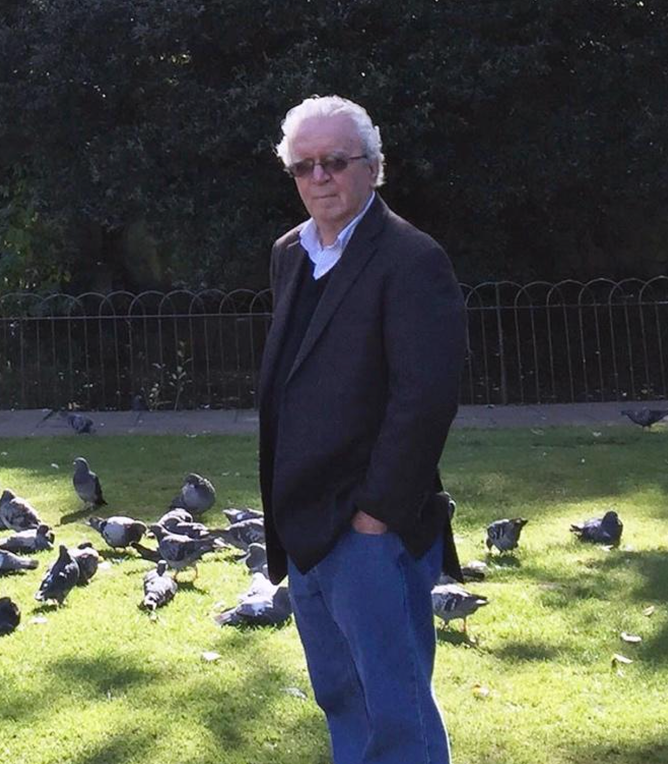

Ed Falco

Steve, we first met in the mid 1960s when we were teenagers and students at SUNY New Paltz. You were already at that point widely read in the classics and poetry and had been tutored for a time by W.H. Auden. How did that come about for you at such a young age and from your background? We were both working-class kids (you from the Bronx and me from Brooklyn), and neither one of us came from families where we were likely to meet an internationally renowned poet like W.H. Auden.

Steve Gibson

I got to meet Auden through a guy I knew in high school who had been writing poems for some time, and he had been sending his poems to Auden and then meeting with Auden about them. He suggested I send Auden some of my poems and so I did, even though I thought the group of poems was terrible. But I did, anyway, and Auden invited me to come down to his apartment at St. Marks Place, to go over the handful of poems that I had sent him. I don’t have those poems and don’t remember any of them, but I remember I was afraid the poems were terrible, and they probably were, but I knew that Auden was an important poet, and I was hoping that he would find something worthwhile in just a part of any of them. And he really was generous and encouraging. When I look back at it, amazingly so. Because what I came away with was—when what he was saying didn’t go entirely over my head—was that writing poetry is making something. When you’re writing a poem, you’re making something. In a letter he wrote to me about the last handful of poems I left with him, he mentioned one or two that he said he’d liked, one in particular, because he thought that one was well made. That stayed with me. Writing a poem, you’re making something.

Ed Falco

I love the way Auden, in working with a young poet, emphasized craft, emphasized the poem as a constructed thing—and it strikes me as a perfect way to think about your poetry—or at least one element of your poetry. Your most recent collection, Frida Kahlo in Fort Lauderdale (Able Muse, 2024) is composed entirely of triolets; an earlier collection, The Garden of Earthly Delights: Book of Ghazals (Texas Review Press, 2016), is composed, as the title acknowledges, entirely of ghazals; and throughout all your eight collections, you’ve included poems composed in a variety of exacting formal conventions. I’ve been especially impressed with the way you handle the sestina, a difficult form to make sound contemporary and conversational—and yet you consistently do that brilliantly. Here’s one I particularly admire, originally published in McSweeney’s (https://www.mcsweeneys.net/articles/a-concise-history-of-leg-amputations)

Sestina: A Concise History of Leg Amputations

Alum, vitriol—for control of hemorrhage—

‘oyle of Elders scalding hot”; turpentine; hot pokers;

pain-relieving cordials; bandages; tourniquets; thread

for sutures; knives, curved or straight; saws

and chisels; bone, soft tissue, skin-flaps; above all, practice—

with leg amputations, there are barely minutes.

“An amputation every seven minutes,”

wrote Napoleon’s surgeon at Borodino. Hemorrhage,

sepsis, and gangrene accompany his practice.

He writes, “Cannonballs cauterize better than pokers.”

At least three men restrain the patient; one saws.

In 70 percent, you can dispense with thread.

Since the invention of gunfire, there’s a common thread:

with below-knee fractures, operate within minutes

(with above-knee fractures, the patient’s dead). Quite often, saws

produce the anesthesia of unconsciousness, as does hemorrhage.

Scrape all devitalized tissue and apply hot pokers

(the “laudable pus” of the 13th century has fallen from practice).

Louis XIV knew the benefits of practice:

a fistula in ano, like a swallowed thread,

wormed through his anus and proved very painful. Blank as pokers,

physicians examined the royal buttocks and knew in minutes—

but surgery? There was the danger of infection and hemorrhage.

Louis’ solution? He employed the old saw

“Practice makes perfect.” In two months, the court surgeon saw

more patients (commoners) than in all his years of practice—

and some survived, for which Louis was grateful. (The hemorrhage

to his treasury was less easily remedied, a thread

historians would later trace to revolution.) In minutes,

Louis’ gamble paid off, while the rest were losers at poker.

In a satiric woodblock print from the 1500s, four men are playing poker:

two are betting the third won’t survive as the fourth saws

through the third’s shin, very determined. In a few minutes

the victim probably will die because it hasn’t yet come into practice

to tighten bands around the leg as a tourniquet. Instead, long threads

of blood spurt into a bucket. If the bucket fills, he dies of hemorrhage.

Coda

It’s hard not to think God likes to play poker or practice with our lives

to correct his foul-ups. Well, Socrates saw the one thread to follow

was Truth—and, in minutes, the poison caused his brain to hemorrhage.

I want to get away from the formal elements of your poetry in a moment to talk more about content, but can you tell us what draws you to employ these difficult forms? What is it about formal poetry that works so well for you? I have my own theory, which is that the powerful emotions and the sometimes-troubling content of many of your poems are kept from overflowing into fury or rage by the restraints inherent in formal constructions? Am I on the right track there?

Steve Gibson

Absolutely. I think that’s part of it, part of the reason I turn to form, like the sestina or ghazal or triolet or sonnet or villanelle, or others, because I don’t want the poem going all over the place or the feeling in the poem going all over the place. I don’t mean by that that free verse lacks form. I mean, most poems I read in journals are in free verse and those I admire don’t run amok in form or feeling. But I think traditional form can help, in helping to concentrate and direct feeling in the work. I mean, look at the narrator in Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” the restraint of that feeling, what he doesn’t say about despair and doubt, or even contemplating ending it. But he doesn’t say that. He points to the horse and says the horse must think it queer because they’ve stopped nowhere, no farmhouse, no warmth, darkest evening of the year, frozen lake, cold as fuck, and he goes back to the horse shaking its harness bells, reminding the narrator it’s freezing. The horse isn’t despairing about life or so depressed it wants to end it. And after that, or maybe because the horse is a reminder of this life, the narrator turns away from those feelings because he has “promises to keep.” I think form helps concentrate tone and content through what isn’t said and what is said.

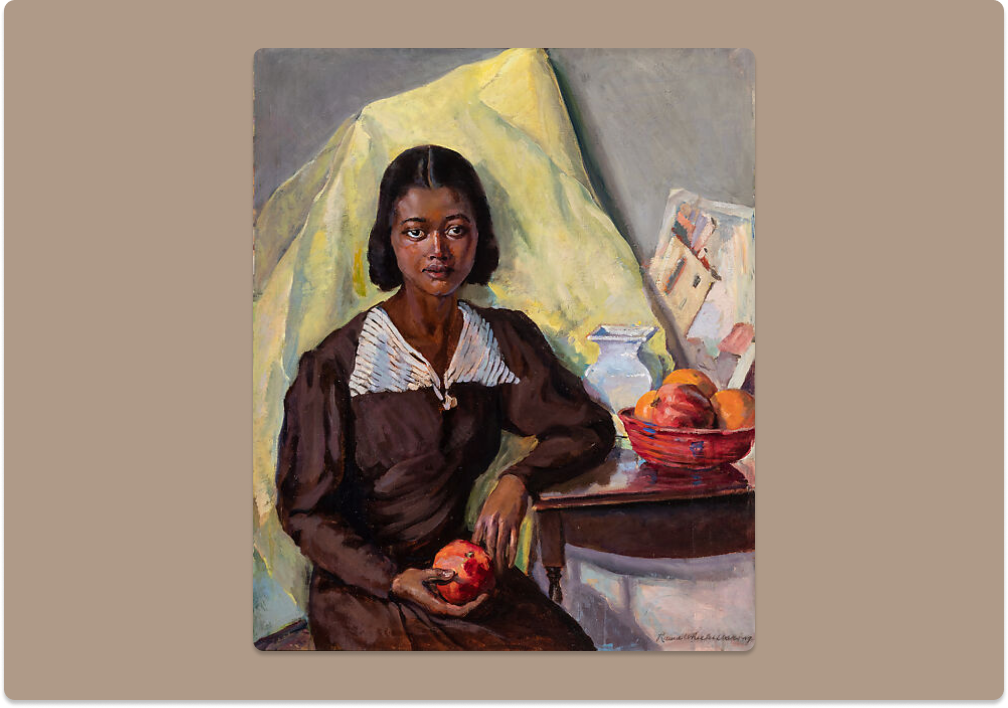

Or look at a poem by Evie Shockley, “step foot,” a sonnet:

step foot

if nothing rhymes with orange toe polish, why

do i wear it? to make my feet stand out

when i step out. they are my alibi,

my good excuse, my reasonable doubt,

my shield. my nails are a caution: don’t touch,

don’t shoot. this orange-with-a-hint of red screams

of confident fuck-yous, but won’t do much

to repel ghosts or bullets. the street seems

safe as any place else. my home’s no less

impenetrable than my body, and

my skin’s no tougher than my heart. just guess

what scares me most: the shit others have planned

in fear of me. so long as i’m deemed danger

i won’t bite my lip, but paint my toes oranger.

Look at the fear and rage contained and let loose—“don’t touch,//don’t shoot,” or “what scares me most: the shit others have planned//in fear of me’’—that’s Ferguson, Missouri; that’s Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. I think Shockley choosing the sonnet in this case makes such concentrated powerful feelings possible.

So, yes, I agree. To go back to your original question, yes, I do think form helps do that for me as it did for Frost and for Shockley.

Ed Falco

Andrew Hudgins in his introduction to Masaccio’s Expulsion, an early collection of yours from MARGIE/Intui’T House, wrote this: “[Gibson’s] formal dexterity is so dexterous it’s almost invisible at the same time that it provides the solid and beautiful architecture of the poems.” That echoes for me what you said a moment ago: “Writing a poem, you’re making something.” So let’s talk about the poems you make. You have a series of sonnets about Degas’ famous “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen,” but rather than focusing on the beauty of the sculpture, you focus on the model, Marie Genevieve van Goethem. Here’s one of the series:

On a Cast of Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen at Art Palm Beach (3)

Her name was Marie Genevieve van Goethem—

she danced for the Paris Opera Ballet, an extra

when Degas asked the teenager to pose for him,

which, of course, she did: first, he noticed her;

second, with adult males you didn’t refuse them,

as you didn’t refuse the company’s rich donors

whenever one tried to grope you behind a curtain;

third, it was less difficult than standing at the bar;

fourth, you did what you were told, without reason,

or else you would become like many an ex-dancer

wishing she had never once sought an explanation.

Who she was: Belgium by birth, one of three sisters,

living in the poorest city area noted for prostitution,

being raised by her laundress-mom, single-mother.

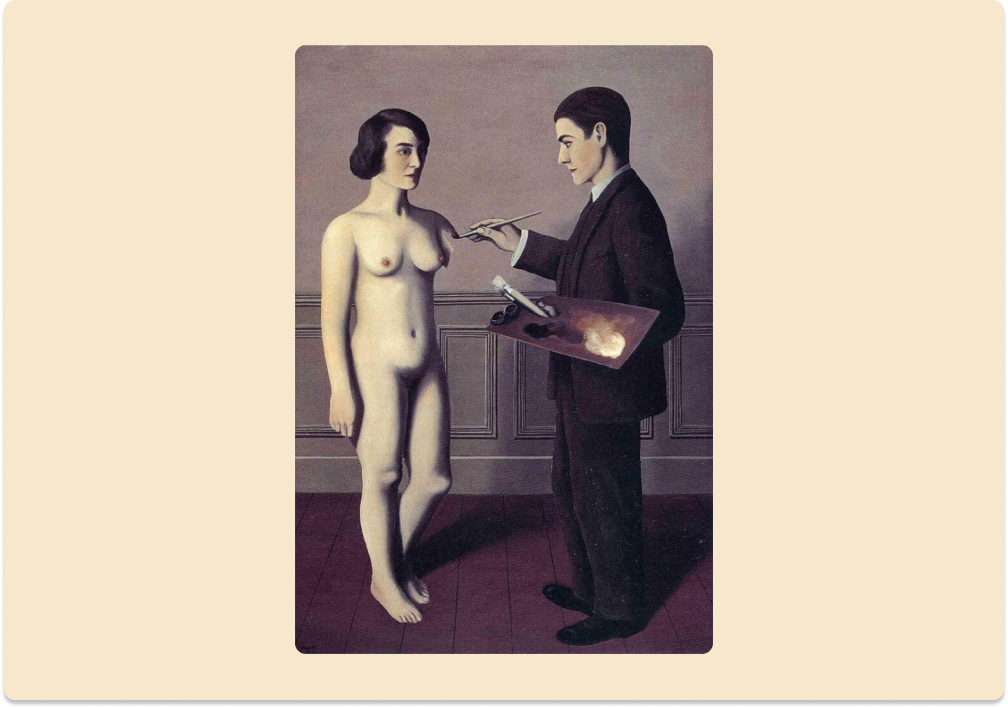

In this poem, and several others, you ask the reader not to pay attention to the beauty of the artist’s work, but to the oppressed cultural position—and often the abuse—of the models. You do the same with other artists and their models, with poems about Lewis Caroll and Alice Lidell, for example; or Bonnard and his mistress (and, later, his wife), Marthe de Meligny; or Gauguin and the Tahitian natives he painted. I read these poems not only as a critique of the commonplace misogyny of the artists, but as a furious rejection of the illusion of beauty in a world, as you see it, that is relentlessly corrupt and cruel to anyone unlucky enough to be caught outside the umbrella of privilege. In the case of the Degas poems, it’s as if you’re insisting the reader see and think about the dark irony of creating a world-renown beautiful sculpture modeled on an abused child. Can you talk about this?

Steve Gibson

Well, I have a lot of conflicting feelings, about many things, and I think those conflicts come out in the poems. It’s not that there isn’t great beauty and wonder in the world, there is; and it’s not that artists don’t add to that great beauty and wonder with their works, because they do. But the world is the world. And beside that great beauty, there exists its opposite, great ugliness; beside that great peacefulness one might experience is its opposite, great anger and violence, because the world is still always the world. I know this all sounds clichéd, and it probably is, but what I think happens is that when I look at something, which really is wonderful, I want to find out more about it, and then the not-so-wonderful rears its head. When I saw that figure of the teen ballerina, I wanted to learn more about Degas making that work. And so I came to find out more about the model, more about who she was, and it wasn’t wonderful. She had a name—Marie Genevieve van Goethem. Her parents were immigrants from Belgium. Her older sister was born in Belgium, but she was born in France (so I’ll have to correct that mistake I still have in the poem you mention), and she lived through some horrors. First, there was the Franco-Prussian War, which France lost to Bismarck’s Germany, which included the siege of Paris, when people starved, literally. I mean, forget the lie Trump repeated in the debate with Kamala that Haitians in Springfield were eating cats and dogs. That was Trump’s bigotry. In the German siege of Paris, people literally did eat their pets. They ate every horse. They stripped wallpaper from walls to eat the wheat glue. They lined up at sewers to club rats, which they called “gutter rabbits.” They killed and ate the animals in the Paris Zoo—including both elephants, named Castor and Pollax. That’s what that little girl, who might have been five at the time, lived through. And the suffering wasn’t equal. The wealthy in Paris ate the best cuts from Castor and Pollax. They had bear claw and kangaroo stew. Served on linen. You can look up the 1870 Christmas menus in those Parisian restaurants, as I did. And when Parisians revolted against the national government, the Paris Commune and civil war followed. In just one week, the semaine sanglante (“bloody week”), between 10,000 to 15,000 Parisians were killed by the national government. And Bismarck, right after France lost and surrendered to Germany, told Aldolphe Theirs, the head of the French government, “not to spare the cannon” in putting down the city’s insurrection.

That’s what that little girl, whose two-thirds life size beeswax statue is in our National Gallery in Washington, D.C., lived through.

And there’s more, the family was piss poor—her older sister, a prostitute, was arrested for trying to steal from a customer. Degas’s teenage ballerina was one of the “little rats” who worked at the Paris Opera where girls were poor, afraid of getting fired, and were expected to put out for season ticket holders. That’s why in some of Degas’s paintings you see those guys in their top hats watching the girls rehearsing at the bar.

Ed, I don’t know if that answers your questions about art and beauty and living in this world, but it’s some of what I think.

Ed Falco

Thanks, Steve, that does answer my question, but I also especially want to note your sympathy for the women who served as models for great artists and were abused or mistreated. This subject matter turns up in so many of your poems that it’s worth emphasizing. I think you’d agree that poems (and all art, really) belong as much to the reader as they do to the poet—and this reader sees in those poems about artists and their models, and many more of your poems, both sympathy for those demeaned by the prevailing power structure—and anger at the structures of power. One of the things I most admire about your poetry is how acutely aware so many of your poems are about the cruelty of those in positions of authority and the struggles of those disempowered. “Long Island Noir,” and “Noir Sestina,” from Rorschach Art Too (Story Line Press, 2014, 2021) are a couple of the many examples of this in your collections. (Rorschach Art Too won the Donald Justice Prize from Story Line Press in 2014 and was reprinted as a Story Line Press Legacy Title in 2021).

In poems like “Ghosts from the Home Front at the Café Central” and “A Crown for my Father on Memorial Day” and “The Odyssey at Horn and Hardart,” you open up to the reader about your relationship to your mother and father in a way that’s deeply personal and moving. Here’s “A Crown for my Father . . . .” (and there’s also a recording of you reading the poem available from Rattle)

A Crown for My Father on Memorial Day

(i)

I have often told stories about you

as a kid I promised not to forget,

like the photo I kept in my wallet

when you were in boot camp in WWII

posing outside your tent—everyone knew

the future would happen but didn’t let

themselves think too much, only to regret

what was in the past they could not undo.

I’d look at that photo and promise you

thoughts of the Bronx River Housing Project

with you home, like that pic in my wallet,

would remain with me forever. Who knew?

That photo, which had serrated edges,

was lost long ago. So much for pledges.

(ii)

Lost long ago, so much for the pledges

to a dead father in a photograph

who stands outside a tent—and almost laughs;

the smile is hard around the edges

and the photo in memory dredges

up memories after the photograph:

an adult, I want to cut time in half

and remember only a boy’s pledges—

but how can you forget what you still know,

cut time in half and remember before

but not ever what will happen later?

It’s not like tearing in half a photo

and pretending you didn’t go to war

or what you did later to my mother.

(iii)

And what you did later to my mother,

a child should never see—court photos

document the violence blow by blow

to justify each restraining order,

which you would comply with, and then ignore.

It must have been I didn’t want to know

and turned my mind off as two shadows

entered the bedroom and closed the door.

The cops would come, as they had come before,

and ask your wife if she wanted to go

with them to the hospital, and she’d say no—

when the door opened, there’d be the neighbors.

This was in the Bronx River Housing Project,

images not in the photo in my wallet.

(iv)

Images not in the photo in my wallet—

nor the image of you in your boxer shorts,

cops helping you with your pants. Their reports

included the weapons, German war helmet,

Nazi flag, and the letters you would let

the cops pretend to read, pretend to sort,

then return to the shoe boxes. You were caught

trying to make sense of what you couldn’t forget—

hence, the war trophies on the bed and letters—

and you going over each one again and again,

and never recalling what you’d done to her,

after you promised it would never happen,

after what you had experienced in war.

Your gravestone marker reads “Tank Destroyer.”

(v)

Your gravestone marker reads “Tank Destroyer.”

I took my wife and kids there on vacation.

At Bay Pines, they gave me a map of the section

and circled in blue your row with the number.

I went there because I had promised her.

I have a wife, a daughter, and a son.

The visit was a side-trip on the vacation.

By chance, in another section was a bag-piper.

I took a photograph of your grave marker.

It gives your name, rank, and division.

You passed away when you were thirty-seven,

the war over, but a casualty of the war

(and as a casualty, I include my mother),

after convulsive-shock and pneumonia.

(vi)

After convulsive shock and pneumonia

you died—buried in Bay Pines, in Florida.

I went to visit as I’d promised her

before your wife died of liver cancer.

I have the map, with section, row, number,

circled in blue ink I keep in a drawer

with batteries, flashlight, if we lose power

in the next hurricane. I live in Florida.

I’m retired. I was a college professor.

My wife of fifty years (also a teacher,

retired), plans trips to our son and daughter

and daughter’s boyfriend in Seattle each summer.

I don’t live in the Bronx River Housing Project.

I don’t have that photo of you in my wallet.

(vii)

I don’t have that photo of you in my wallet

because I lost it a long time ago,

but I do have the cemetery photo—

it’s on my bookcase. I don’t want to forget

that at City College, you wanted to get

your CPA, the war came, you had to go:

That’s you outside that tent in the photo

and the future hasn’t happened, not yet,

and nothing is lost—the photo, the wallet,

the you (almost) smiling because you know

that’s how she needs to see you as you go

off to a future neither of you could expect.

The past is past; what’s done, we can’t undo.

I have often told stories about you.

That final line is wonderfully resonant with themes of love, loss, respect, and longing: “I have often told stories about you.” Can you talk a bit about the impulse to go back and look at elements of your own history through the medium of poetry? (I wonder now, as I write this, if you think about your readers when you’re in the act of writing poems, or are you telling a story as it rises up within you in the act of writing and not concerned in that moment with potential readers?)

Steve Gibson

Yes, I do think about the reader, but not consciously beforehand. First of all, because when I sit down to work, unless I’m revising, I don’t know what I’m going to write. I don’t know what the subject is going to be, though somewhere in the back of my brain something is going on and it’s up to me to try to find out what that something is, and then the writing itself becomes the kind of discovery of what I was looking for in terms of subject, what I wanted to say about said subject, and how I want to say it.

I don’t know whether you’re aware of it or remember it, but I used to write one word at a time, very slowly, and a poem would take forever, and then when I turned to writing fiction, I couldn’t do that, and you told me just to push the story through to the end. Just get it done. And that’s what I did with the stories I wrote. And that changed how I wrote poetry. Push it through to the end, get it down, and be ready to revise it later. That’s what I do. I have so many versions of poems that I have to number them, and that still doesn’t mean I won’t go back to the same subject again even when a poem I’ve written on that subject gets published.

But to go back to your question about having the reader in mind. As I said, I don’t think I consciously have the reader in mind, but I want the reader to be able to relate to what I’m writing, to the stories I end up going back to time and again, telling and retelling them, thinking about those stories differently, and so writing about them again. There are no do-overs in life, but writing gives me the chance to understand what I couldn’t then or wouldn’t later.

Remember Irving Weiss, our fellow teacher and friend? When I bought his translation of Malcolm de Chazal’s Sens-Plastique —this is over fifty years ago—Irving wrote in my copy, “Whatever matters, words do.”

I think that’s something worth passing on from one writer to another.

Ed Falco

I like the idea of writing giving you a chance to understand in the meditative and creative process of making the poem what you couldn’t or wouldn’t in the chaos of the lived experience. That’s seems like an excellent reason to explore your own history, and, as you say, to go back to the same subject again and again as your thinking about it develops and changes. And Irving Weiss! He was such a great guy—and he and his wife Ann were good friends of Auden, so yet another Auden connection. I still have my copy of Sens-Plastique (with the introduction by Auden).

One final question. Your wife, Cloe Veltri Gibson, is also an artist, a watercolorist and painter, and you two have been together since your late teens. What role do you think Cloe has played in your development as a poet? I know for years she read every draft of your poems. Has that changed as you’ve become more prolific? Maybe also talk a little bit about being a father, a husband, and a poet, about your role as father to your son, Joe, and your daughter, Kyla, and a husband to another artist. How do think your domestic life has influenced your life as a poet?

Steve Gibson

Cloe still is, and almost all of the time always was, my first reader. I actually got to know her, and her me, in part, through poetry, before we’d even met. I’d written this poem called “Another Penelope,” which a girlfriend of hers had and showed her. My wife liked the poem, and one thing led to another. That’s how we ended up meeting. So she’s been reading my poems right from the get-go.

And she’s a terrific reader. She’s usually right on the mark when something is or isn’t working as it could be in a poem or isn’t working at all and she questions why it’s even in there. And of course, when that happens, it takes me awhile, one, to stop thinking she doesn’t know what she’s talking about, like I feel about most criticism by an editor, which is really what she’s being when I’m showing her a new work, or even a revision. She takes on the role of editor because that’s what I’m in essence asking of her, her view of what the poem needs. Sometimes, the problem pointed out isn’t even a problem, really, like a grammatical reference being assumed but not working, but at other times, it’s more, like the poem going off in a direction that she questions, and I too may have questioned but allowed myself to overlook, but then her reading of the work and coming to that same difficulty is really something the poem needed.

So, yes, she’s absolutely been terrifically important, and terrific, as a reader.

And I agree with your suggesting that Cloe as an artist in her own right makes her a formidable reader, because I think it does. She’s a terrific artist, technically and intuitively. She’ll go to a subject because she’s somehow drawn to it and then she stays on that subject for as long as she has to, for as long as that subject compels her, and then she moves on to some other subject and sinks her teeth into that one. And I mean that cliché—because a painting of hers in subject may appear delicate in treatment, but she’s gotten down to the bone in it. I think that’s what I enjoy so much when she asks me to view what she’s working on. I’ll think something is done or something is changed but it hasn’t been except by something else in the painting being changed which alters the appreciation of the earlier thing that wasn’t changed—and that to me, when I think about now, is how I think poetry works, one change affecting the other, even if the other in itself isn’t changed. And so, yes, her being an artist herself, makes her a terrific reader. I know, when you’ve sent us a draft of something new that you’re working on, I’m always anticipating what she will have to say about it. And almost always, she’ll take into account things that I haven’t. And she’s done that with our son, Joe, who’s written screenplays, or with our daughter, Kyla, when she was a keyboardist with her band Kissing Potion, and they were bringing out their first album—my wife grew up in an Italian-American household where her grandfather, an immigrant from Calabria, took her to the opera in New York City before she was old enough to have to put a token in the subway turnstile.

My wife has an artist’s great eye and great ear—and even greater instincts.

Anyway, apologies for all the rambling, but I think that’s why she’s always been a terrific first reader.

As for the “domestic life” part of your question as it relates to poetry and my being a poet, you know, as a father, there’s your life before and there’s your life after you have children. I know I had a life before Ky and Joe, as Cloe did, but I can’t imagine a life after without having had the three of them in it. But poetry doesn’t pay the rent either. So I’m forever grateful to Palm Beach State College that the college allowed me to teach at their Belle Glade campus out in the middle of almost nothing but sugar cane and vegetable fields for thirty-two years—and make no mistake about it, those were great kids out there, great students, and still are, no matter how much the current administration in Washington tries to demonize color.

But that won’t last forever. As Auden said “In Memory of W. B. Yeats:”

“For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its saying where executives

Would never want to tamper; it flows south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.”

Thanks, Ed, for this, and a lifetime of friendship.

Ed Falco

Crazy how the years go by, Steve. I thought we’d never again see a period of time as convulsive and at times frightening, heartbreaking, and dangerous as the 60s and 70s, with the Vietnam war and the assassinations and riots—but here we are again, in maybe an even more dangerous era. Through it all, thankfully, there have been poets and writers like you and so many others whose faith in words—in the power of poems and stories to reveal moments of truth—has been and remains a guiding light. Endless thanks.

Steve Gibson

You too, Ed. Same back at you.

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

%201.png)

.png)