Love Poems in Translation: How to Love in Sanskrit

Conversation with Anusha Rao and Suhas Mahesh on translating and curating Sanskrit love poetry for modern readers while exploring the challenges of bridging ancient verses with contemporary sensibilities

Shannan

How and when did this project begin, and why?

Anusha & Suhas

In some ways, we have always been working on the book—we keep reading, by ourselves and together, and collecting interesting verses. As one Sanskrit poet asks: can you really contribute to a conversation if you have no lovely poems to quote? But the book was conceptualized when we asked ourselves why we see people reading Rumi and Dante in airports and cafes, but not Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti. Our contention is that this is not the fault of the Sanskrit poets, but of those who have curated and translated them in ways that readers today cannot appreciate. Many of the poems in our book have been read in an unbroken fashion for over two thousand years, but almost always in the original language.

Translations of Sanskrit really began 200 years ago, but we have produced very little that can be appreciated in homes, cafes and book clubs. This troubled (troubles) us. On a more personal note, we just wrote the book that we would have liked to read as we navigated a long-distance relationship built on a shared love of Sanskrit poetry. We seriously began work on the book a while before the pandemic, spending every evening for two years reading various sources to find these two hundred-odd poems, before we began working on the translations.

We examined over ten thousand poems from about one hundred and fifty texts spanning 2000 years of literature – this was the most time-consuming aspect of the process.

Shannan

In the Introduction, you note that “these poems have been selected keeping the general reader in mind.” When we think of translation, we don’t often first think of the reader, the receiver. We might consider the text itself and then the author, their intentions, and their context. And then the market into which we are translating or bringing forth the translation. The reader base might already be established if the book to be translated is popular enough. And yet, the reader really does lie at the heart of any writing endeavour. Writers are almost rendered marginal in that contact point between words written and words read.

Later on in the introduction, you give a word of caution to readers, giving the example of “an innocent village girl [who] pours out her feelings” – asking readers not to conflate her with the composer of the piece, the writer. Is there a greater separation between writer and reader regarding translated works? Ought the latter be given more importance when the translator works, even if it means certain elements of the original are left on the editor’s table?

Anusha & Suhas

While translating works not far removed from our time, the reader, author and translator usually inhabit similar social frames of reference. This gives translators the freedom to emphasize the text and the author. However, the situation is more complicated with pre-modern material. The translator has to translate words and ideas, but also translate the social specifics of a civilization that is no more before the eyes of the reader. Not everything can be translated this way, and even when it can, it can leave a poem reading more like an encyclopedia entry than a poem.

A translator has no choice but to leave certain elements on the table. What elements do we leave on the table? Thankfully, the Sanskrit tradition provides us with some pointers here, by telling us that the soul of poetry lies in the rasa or aesthetic flavour it conveys, which in turn lies in what is not explicitly said. The syntax, meter, alliterations and the rest are flourishes, but they are not the soul of poetry. And so, we have been minimalist in our translations, preserving the "soul" of the verse and ignoring the flourishes. Particular flourishes do not transfer well to English, and even when they do, they can distract from the soul of the poem.

Shannan

In the Introduction, you note that “these poems have been selected keeping the general reader in mind.” When we think of translation, we don’t often first think of the reader, the receiver. We might consider the text itself and then the author, their intentions, and their context. And then the market into which we are translating or bringing forth the translation. The reader base might already be established if the book to be translated is popular enough. And yet, the reader really does lie at the heart of any writing endeavour. Writers are almost rendered marginal in that contact point between words written and words read.

Later on in the introduction, you give a word of caution to readers, giving the example of “an innocent village girl [who] pours out her feelings” – asking readers not to conflate her with the composer of the piece, the writer. Is there a greater separation between writer and reader regarding translated works? Ought the latter be given more importance when the translator works, even if it means certain elements of the original are left on the editor’s table?

Anusha & Suhas

While translating works not far removed from our time, the reader, author and translator usually inhabit similar social frames of reference. This gives translators the freedom to emphasize the text and the author. However, the situation is more complicated with pre-modern material. The translator has to translate words and ideas, but also translate the social specifics of a civilization that is no more before the eyes of the reader. Not everything can be translated this way, and even when it can, it can leave a poem reading more like an encyclopedia entry than a poem.

A translator has no choice but to leave certain elements on the table. What elements do we leave on the table? Thankfully, the Sanskrit tradition provides us with some pointers here, by telling us that the soul of poetry lies in the rasa or aesthetic flavour it conveys, which in turn lies in what is not explicitly said. The syntax, meter, alliterations and the rest are flourishes, but they are not the soul of poetry. And so, we have been minimalist in our translations, preserving the "soul" of the verse and ignoring the flourishes. Particular flourishes do not transfer well to English, and even when they do, they can distract from the soul of the poem.

Shannan

You give a “tour of the translator’s workshop” before the book effectively begins, providing the delightful analogy of a Sanskrit poem as a glitzy Indian wedding and the Sanskrit translator who must now “replan it as a solemn church wedding in England.” You also introduce the idea of the translator as a curator. Sometimes, translation feels to be more the scholar’s domain than the creative writer’s. Would you say this is correct, or is the approach more nuanced? I’d also love to hear more of your personal experiences in choosing what and whom to translate for this collection. Were there debates between the two of you? How did you move through other technical and creative complications? Furthermore, considering the linguistic richness and the layered meanings in Sanskrit, how did you navigate the potential loss of nuance in translation while maintaining the poetic integrity of the original texts?

Anusha & Suhas

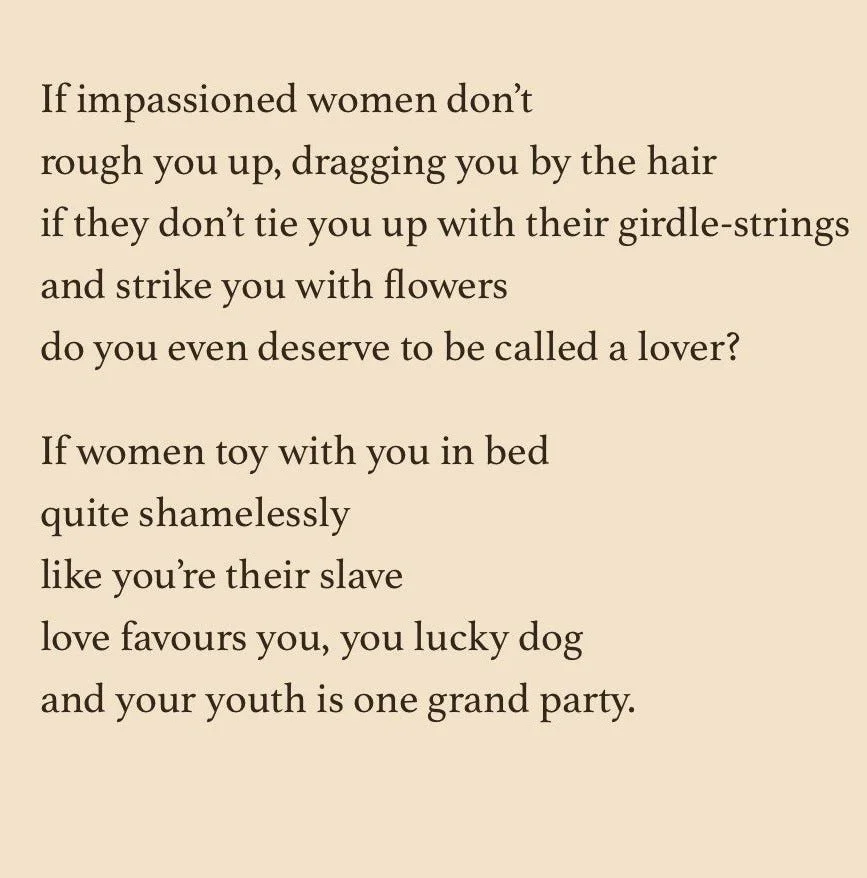

On one end, we have translators who go to great lengths to emphasize exactitude, even translating the description of a garden by listing the scientific name of every tree. These translations are for scholars by scholars, and the public can find little enjoyment in them. On the other end, we have translators who play to the gallery, interpreting source material as loosely as they can. Popular translations of Rumi and Songs of Buddhist Nuns (Therigatha) come to mind. As the noted Pali scholar Bhikkhu Sujato observed about a wildly popular "translation" of the Songs of Buddhist Nuns, sometimes called the world's first feminist poetry: "The reason that the poems sound 'fresh' and 'relevant' is because they were literally written a couple of years ago by a guy in California." Our poems sound very fresh and relevant too, but for a different reason. We spent an enormous amount of time reading an enormous amount of material to identify where the ancient world and our world resonate. This allows us to translate in a "fresh" way without the original. As an outcome of our curation process, our book cannot claim to represent all of Sanskrit love poetry. But can any single book really represent a tradition that spans two thousand years and a million square miles?

Having two translators made the process twice as challenging, and the result twice as rich. We translated poems individually and then discussed our readings together, gradually converging on the best possible representation of each verse. Like all good poetry, Sanskrit poetry too leaves plenty unsaid. We would often disagree whether the speaker was a man or woman, or what the social context of the poem was. We would turn to old commentaries and discover that scholars disagreed about the same things hundreds of years ago too. How did we maintain the integrity of the text? We are fortunate to be translating from a tradition that makes a fine art of analyzing what the implied meaning of a poem is. This is sometimes overdone in the tradition – there is a medieval commentary on Amaru's Hundred, the most celebrated anthology of Sanskrit love poetry, that re-reads it as an extended spiritual metaphor. Sometimes the overreading goes the other way – commentators on another celebrated anthology —Seven Hundred Gahas — give erotic undertones to even simple descriptions of nature. But for the most part, we have an invaluable tradition of commentaries telling us how the greatest minds across centuries read some of these verses. This gives us reasonable confidence in our work—that we are not reading into a verse what is not already in it, and that we are not missing the key point of the verse.

Shannan

I love the way you’ve laid out the individual chapters. Framing this, unabashedly as a “How to” guide at once adds an oddly playful, even commercial twist to the idea of a book of Sanskrit love poetry. Could you discuss the hermeneutical methods you employed to organize and interpret these poems? More specifically, I’m also curious to know how you handled the expression of concepts such as 'rasa' and 'bhava'?

Anusha & Suhas

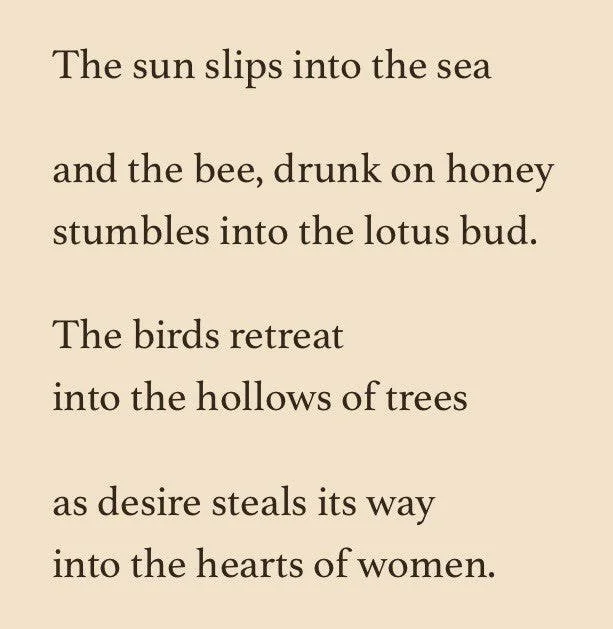

Within Sanskrit anthologies, romantic and erotic verses are categorized in some standard ways—for instance, you might see a series of poems on the go-between, usually the heroine's friend who gets despatched to the lover with a message, or a series of verses on how women experience pangs of separation during moonrise. We did not want to use this structure in the book because these depend on conventions very unfamiliar to today's readers. Given that the world of Sanskrit poetry is already an unfamiliar and distant world, we did not want to distance it further with too much context—our intention was to jolt the reader with the familiar and inspire a deeper exploration. And so, we structured the book by the stages of a contemporary relationship—flirting, making love, yearning, and even breaking up. We also added titles to verses where the source has none as a form of explication—sometimes to point the reader at the implied meaning; at other times to link the verse with a familiar trope or idea.

Shannan

How does your translation of Sanskrit literature contribute to the dialogue between Eastern and Western literary traditions, particularly in terms of conceptualizing and expressing love?

Anusha & Suhas

General audiences usually approach Sanskrit in one of two ways. Sanskrit is a sternly religious language, filled with hymns, mantras, and other appurtenances of ritual, yoga, and meditation, and it should stay that way. Alternately—many thanks to Richard Burton— Sanskrit is the strange, debauched language in which the Kamasutra is written. Who knows what other depths it plumbs? These stereotypes are utterly false – especially when it comes to poetry. Latin and Greek have public-facing scholars like Mary Beard and Emily Wilson. This has not been the case for pre-modern Indian literature, at least not in the Anglophone world. Even the few public-facing books out there are not really public-facing– the reader needs quite some background (and motivation) before they can be enjoyed. What is the flavor of Sanskrit poetry like? We see our book as a first step towards communicating this to an audience unacquainted with Sanskrit.

Anusha Rao is a scholar of Sanskrit and Indian religion who likes writing new things about very old things. She is currently pursuing a PhD at the University of Toronto, and writes a column in the Deccan Herald presenting witty Sanskrit-flavoured takes on contemporary issues.

Suhas Mahesh is a scholar of Sanskrit and Prakrit with a terrible weakness for good verse, rare manuscripts and arcane grammar. By day, Suhas is a materials physicist with a PhD from the University of Oxford where he was a Rhodes Scholar.

.png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

%201.png)

.png)