5 Poetry Collections from the US-Mexico Border

Poetry about borders and other man-made limiting concepts, about their transgression and transcendence

In the 1930’s, the United States deported some two million people of Mexican ancestry, including more than 400,000 US citizens, a travesty the poet Jacqueline Balderrama excavates in her 2020 collection Now in Color. With the incoming US President threatening to deport record numbers of immigrants, there’s no better time to read Balderrama and other poets who write from the US-Mexico border. No, they cannot tell us how to fix our broken immigration system or exactly where to concentrate our protests against injustice. What they can do is teach us to see through the crisis reporting and heated rhetoric to the complicated realities of the border: an ancient, beautiful, and unforgiving desert landscape through which humans have migrated for thousands of years, now scarred by militarized fences and criminal cartels. Poets like Benjamin Alire Sáenz, who has interrogated and integrated his own complex identity as a queer Mexican-American, can help us make our own way through polarized debates, reject an “either/or” mindset in favor of “both/and,” and ultimately come to terms with the US’s own contradictory and amnesiac attitudes toward immigration. Crucially, these five poets writing from the border do not write only about the border; their work surveys the full, rich range of their experiences and preoccupations, both surprising us and reminding us of what connects us all in our common humanity.

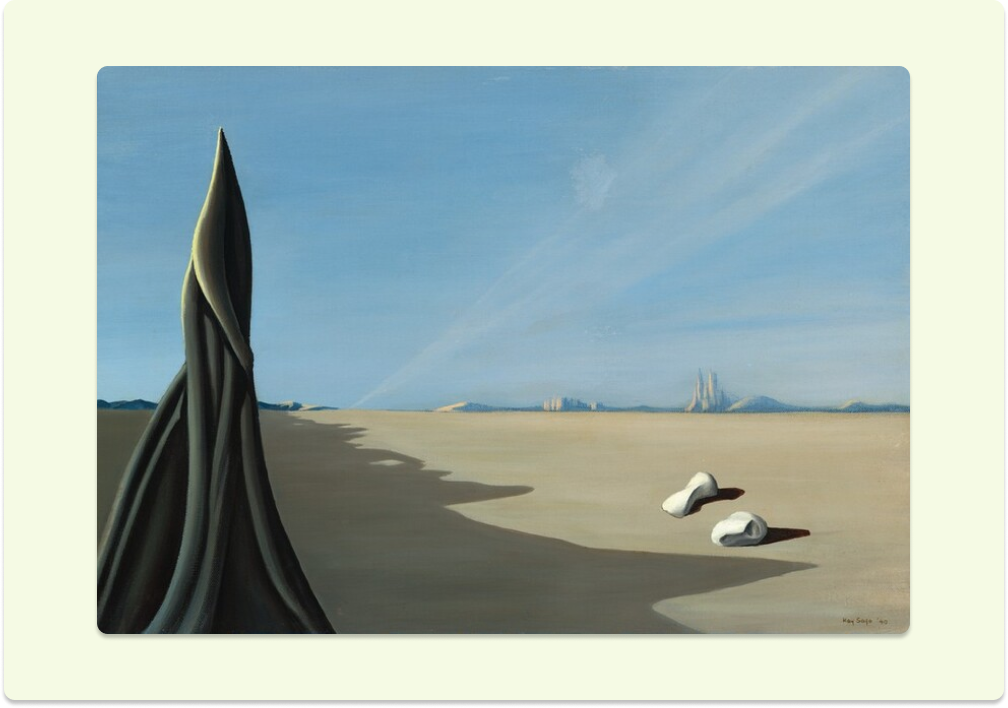

The Book of What Remains by Benjamin Alire Sáenz

Copper Canyon Press, 2010

The political is deeply personal in this collection by acclaimed El Paso author Benjamin Alire Sáenz. The poet is a bilingual Mexican-American with ties to both El Paso and its Mexican sister city, Ciudad Júarez. He is also a former Catholic priest; a gay man with an ex-wife he clearly still cares about; and a writer from a blue-collar family that doesn’t really consider his occupation work. As such, Sáenz is skilled at holding space for two conflicting ideas at once; an appropriate word to encapsulate his obsessions might be “transgression,” whose Latin roots mean literally “to go through to the other side.”

The desert is front and center in this collection: a series of eighteen short poems, each titled “Meditation on Living in the Desert,” open and close the book and cleanse the palate between longer poems throughout. “I want to live forever,” Sáenz writes in one “Meditation,” “But only if I can continue living in the desert.” But he also recognizes the contradictions inherent in such a home: “I love the sand, the heat, the arid nights./ …I am also in love with air conditioning.” With a flinty honesty that keeps their naked emotion from becoming maudlin, poems like “Meditations on Music, Joseph McCarthy, and My Grandfather” find intimate moments within the grand sweep of history. A beautiful long poem called “Last Summer in the Garden” invokes Eden as a backdrop both for the author’s divorce and for the millions of migrants and refugees exiled from their homelands by violence or poverty: “God/ Writes letters that spell out exile on the backs of hungry people./ They’ll do anything to get into countries that have trees teeming/ With fruit.” Sáenz wants his readers to see these hungry people, and to think deeply about the historical and political forces that shape their choices. “Thinking/ is a kind of work,” he notes dryly. “A kind of work that’s really hard. People should/ do more of that.”

With the River on Our Face by Emmy Pérez

University of Arizona Press, 2016

This collection coalesces around the river that forms the border between Texas and Mexico, called the Rio Grande in the US, the Río Bravo in Mexico. Poet Emmy Pérez has lived all along the river, from El Paso to McAllen, and her poems bristle with opuntía cactus and flowering lantana, with ocelots and vermilion flycatchers. Pérez is enamored with language as its own kind of sonic river. “Language can be so sexy./ It turns me on, consonance.” In a long central poem called “Río Grande~Bravo,” she explores the river as a metaphor for poetry: “Poetic line/ Rushing to the mouth.” But the border wall interrupts her reverie, a “concrete abstraction in front of our face”. Development and militarization, Pérez reports in “The Valley Myth,” have destroyed the desert landscape: “The myth begins with no more nopales, víboras, and sacred hierbas….it uproots hundred-year-old sabal palms and plants concrete footings for steel column walls… It says great-tailed grackles and white-tipped doves prefer asphalt parking lots.”

Pérez writes in direct conversation with Gloria Anzaldúa’s feminist masterpiece Borderlands/La Frontera. But she also reserves the right to draw inspiration from anywhere she damn pleases. “Downriver Río Grande Ghazalion” begins as a traditional ghazal, but then breaks into a Spanish couplet that displaces the radif, the repeated end word. Things only keep diverging from there, with couplets morphing to a river of words that snakes down the page. The poem assembles a menagerie of native species—“Snake, bobcat, great horned owl, pauraque, bats, tlacuache” (a Nahuatl word for the Mexican possum), and “burrowing vato owls,” alongside a reference to Agha Shahid Ali, the Kashmiri American poet and ghazal master. Justifying this marriage of distinct traditions, Pérez writes, “Sin fronteras. Linked by rhyme, refrain, y su nombre de diosas / & colonizers…It’s time to move beyond binaries.” One line from this poem might serve as a motto for the entire collection: “The scent of water. A tolerance for ambiguity.”

Now In Color by Jacqueline Balderrama

Perugia Press, 2020

Balderrama’s debut collection is structured around a series of thirteen poems formatted as dictionary definitions—or more accurately as translations, since the single title words are Spanish (“sonar,” “oscuro,” “criatura”) and the text is English. Rather than transliterating each Spanish word directly, the poet relates more oblique connections, “grafting associative memories,” as she says in the book’s endnotes, and claiming the language for herself as a “non-Spanish-speaking Latina” who seeks to “diversify what it means to be Latinx.” Between these translations are poems that cut together the poet’s family lore with the intertwined histories of the US and Mexico, images from the Golden Age of cinema, and modern-day horrors like the separation of migrant children from their parents at the border.

Some poems explicitly and movingly address recent border crises; of the unaccompanied Central American children that arrived in large numbers in 2014, Balderrama writes, “Their homes have melted in the crossfire.” But this collection is much more than a response to current headlines. It engages with migration in a generational context, part of an intimate family story that the poet’s experience both traces and transcends. Balderrama is preoccupied with borders of identity and language, with the line between reality and its representation (in art, in movies, in mirrors). She finds a touchstone in the actress Rita Hayworth, whose original name was Margarita Carmen Cansino. In “Study of Self-Portrait” Balderrama reflects on the actress’s choice to change her name: “And then do most stop asking/ Where where where/ soft sirens/ are you from”. It’s a study of how we create ourselves: not from scratch but through adaptation and assimilation, both constantly changing and staying essentially the same, as the poem’s final line affirms: “Remain/ Become/ Remain/ Become / Remain/ Become”.

Every Day We Get More Illegal by Juan Felipe Herrera

City Lights Books, 2020

The child of migrant farmworkers, Juan Felipe Herrera was US Poet Laureate from 2015 to 2017, the first Chicano (and first Latino) to hold the post. In this collection he casts his lot with the undocumented immigrants whose labor keeps this country running. The prose poem “You Just Don’t Talk About It” throws down a manifesto of sorts: “you do not care about those who fight for you write for you live for you act for you study for you dance for you inform you feed you nanny you clean you… the assault the segregation the jailing the deportations upon deportations the starving the ones curled up on the freezing detention corners because they wanted to touch you to meet you against all odds”

These poems travel. Sprinkled throughout the book are six very short pieces all titled “Address Book for the Firefly on the Road North,” which locate their migrant speakers in geography and history. In another sequence titled “[interruption],” we run headlong into the border wall, realized not only as a physical barrier but also a symbolic one: “it is more than an arbitrary stop …it is/ an arrangement of agreements of always-war.…” But the wall doesn’t get the last word: “we continue on with the new exemplar of what life is the one/ we carry as we pass as our ancestors have for more than 170 years.” One of the most personal poems here is “Enuf,” in which the poet remembers, “used to think I was not American enuf/ used to think I would never be American enuf… / not even in the welfare offices where I employed/ superb translation skills for my mother”. Herrera reminds us that his story “is not a poor-boy story/ this is a pioneer story/ this is your story/ America are you listening”

Not Go Away Is My Name by Alberto Ríos

Copper Canyon Press, 2020

In this collection’s third poem, “Border Boy,” Alberto Ríos writes: “I grew up on the border and though I left/ I have brought it with me wherever I’ve gone./ Its line guides me, this long, winding thread of memory.” Like other poets discussed here, Ríos negotiates the border as both structure and symbol: “It is not a place out there but a place in here. / I catch on its barbed wire in both places.” Ríos is savvy to how politicians and reporters use his home territory for attention: “If the ratings for The Border would just go down, / We could cancel it.” He laments what the border has become: “The border I knew was something with a history./ But this thing now, it is a stranger even to itself.” But he also rescues that history by giving us detailed, lovely scenes from everyday life in the borderlands: Sunday afternoons gathering over tamales, minor league baseball teams playing exhibition games, winter mornings when the Sonoran Desert hums with animal life.

A recurring theme is the weight and power of memory. In the title poem Ríos writes: “We are at war. You always win. / But I do not go away.” He counters the violence and dehumanization of the border’s military industrial complex with memory’s quiet insistence: “You shoot with bullets, but you have nothing else./ …You set fire to me with gasoline. / I set fire to you with the memory of your first love.” Ríos praises the power of quiet persistence, of invisible effort, of the ignored but essential underpinnings of our lives. “What is quiet is also strongest/ In that it does not walk away.” One poem is an ode to the many migrants who cross the border only to disappear into the shadows of American society: “Being invisible will be his work even after he stops walking. / Being quiet will be his life.” Ultimately, this is a hopeful book. The next-to-last poem, dedicated to Ríos’ granddaughter, revises the poet’s earlier admission of defeat: “The bad do not win—not finally,/ No matter how loud they are./ We simply would not be here/ If that were so.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

%201.png)

.png)