Between Visible and Invisible Worlds

On ecological dread, contemporary fables, and embracing uncertainty

KARAN

Chris, these poems stunned me — they’re saturated with intelligence and wonder, but never veer into abstraction. You manage to hold grief, absurdity, language-play, and ecological dread all in the same container, and still leave room for beauty. There’s something in here that reminds me of what C.D. Wright said: “It is a function of poetry to locate those zones inside us that would be free, and declare them so.” Let’s begin there: What compels you to write poems in this moment, Chris? Where do your poems tend to sprout from — an image, a voice, an ache?

CHRIS

I think the ache I feel to write poems at fifty-five is the same ache I felt as a teenager to create something, anything. Poetry is what found me and said, kid, this is what we have for you. You can do this. I’ve been writing ever since. But to answer your question more specifically, my poems start with an image or an idea or even a title. As for a voice, I’ve built mine from listening to other voices who have been important to me over the last twenty five years: Larry Levis, Philip Levine, Kim Addonizio, Bob Hicok, Kevin Young, etc.

KARAN

In “Bureau of Useless Splendour,” you write: “Already / this story is a fable, is fabulous, is becoming more true / with every passing moment.” That line felt like a thesis for this whole packet. Your poems read like contemporary fables — full of speakerly intimacy but also mythic estrangement. Do you feel your work operates in a space between truth and fabulation? What does the lyric allow you to say that discursive or narrative modes can’t?

CHRIS

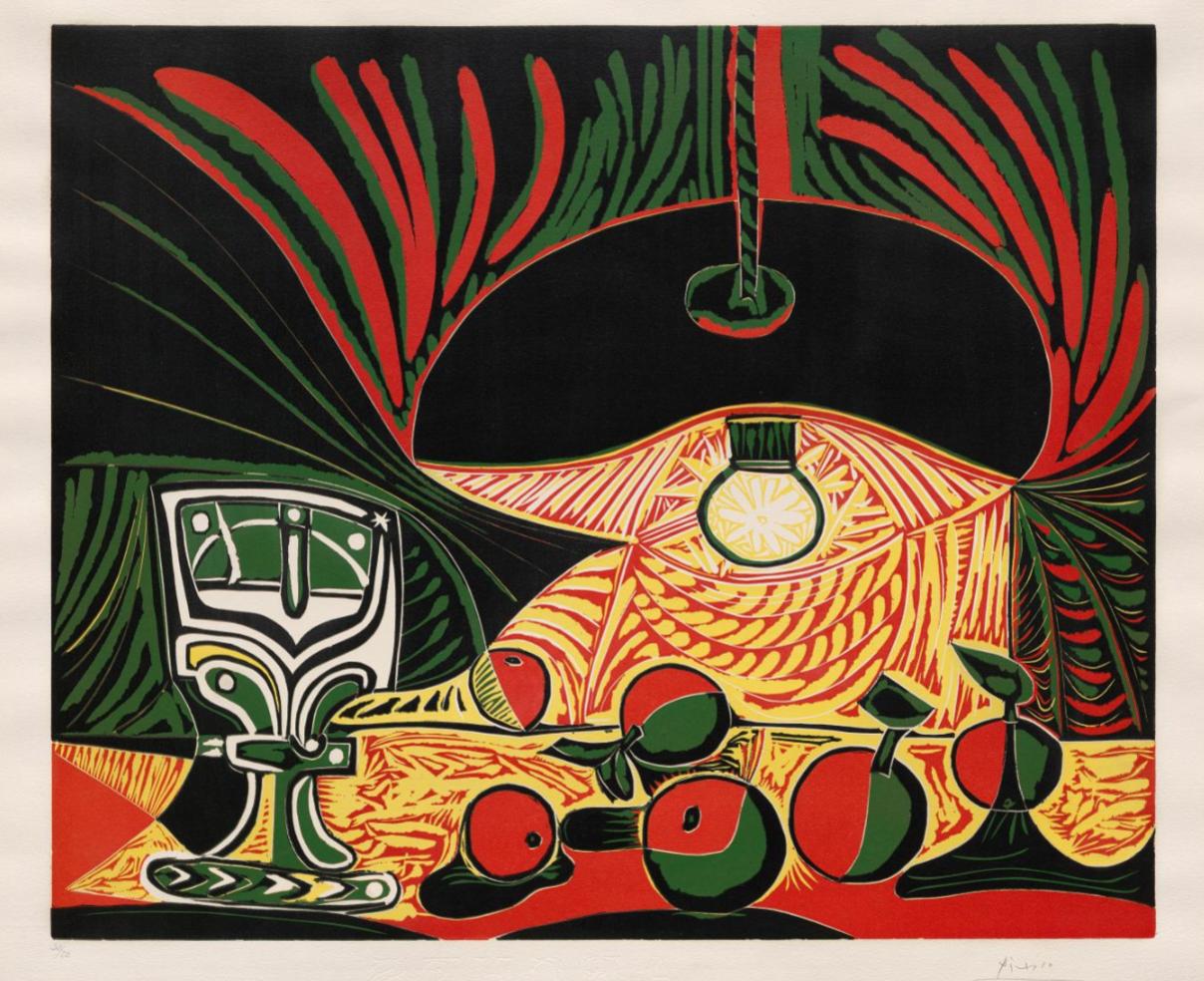

Wow! Love this question! I really see poems this late in life as a kind of polyphonic sculpture or visual-verbal collage. My first three books were lauded in Canada–with my first book Bonfires even winning a national award–and very, very narrative in their focus, but the poems in those first two books, in particular, feel now almost like vignettes. The poems I find most exciting now are the ones that play with high and low registers, and word-play, and surprises! I want to be surprised by what a poem offers, and the more I moved away from realism, the more inventive and more fabulous my poems became! I want my poems to begin in delight and end in wisdom, as Robert Frost once said. I believe that.

KARAN

One of many memorable lines is in “Daydreaming in the Anthropocene”: “My personal pronouns are Inside/Spirit, It/NoMan.” It made me laugh, then made me wonder: what does it mean to locate the self in a collapsing world? Are these poems acts of resistance, surrender, or something else entirely? How do you think about identity — especially masculine identity — in relation to the planetary crisis?

CHRIS

I’ve written about the masculine identity, especially toxic masculinity, in a poem called “Male Ego” in my book Deepfake Serenade. I wrote: “Little caged animal growling in my ribcage, / telling me I am so much more than stardust, / interstellar debris…….the way / you try to mansplain history.” I think that is it for me. I don’t want the masculine to define or to mansplain how I look at the world entirely. Clearly, I am myself in my body, but my self –especially my writing self—really retreats from being too comfortable with gender and identity, especially in light of the climate crisis we are all facing. Really, I like when writing to enter that liminal space between past and present, self and unself, the visible and invisible worlds.

KARAN

“Olympus Mons” is such a beautiful refusal of apocalypse fantasy — essentially, you’re saying: I want to stay here, where the coffee is overpriced and kids bounce on trampolines. “What might I say if I found / myself walking the red dust canyons...? I would say Home. I miss home.” There’s something so emotionally grounded in that, and I resonate with it a lot. Will you speak about the nuance at play here — sure this world is fucked, but it’s the only one we have, and some such?

CHRIS

Yes, I think it’s folly to think we are going to terraform Mars and make it habitable for humans when we can’t even keep the thermostat constant on Earth. I mean, the world is at least 50 percent terrible as Maggie Smith rightly said in her poem “Good Bones,” but delight and wonder and the search for truth and beauty still give my life a lot of meaning. Sitting on a back deck, watching little kids jump around on a trampoline, that is the good stuff. Poetry, art, family, some old lady’s flower garden, this is what life is all about. At least for me.

KARAN

There’s something elegiac and riotous about “Requiem for the American Meme” (what a great title!) and totally hilarious as a subject for a poem. I love the cultural scaffolding on display. It’s clear to all of us that something is collapsing, but what is it? How do we avoid it? I know they’re large questions, so I’ll end with this: How do you think about encapsulating our current moment without falling into either despair or parody?

CHRIS

Not to sound grave, but I fall into despair all the time. I am a chronic major depressive so I live with that knowledge. But what pulls me out of that particular dark riptide, those dark thoughts that want to suck me under and drag me out into a sea of self doubts and old hurts, is light “whispering to the cherry blossoms” or my kids taking a “selfie” which, at least for me, is this really grounding thing which says “Hey, look at me! I’m here!” which is such a terrific self affirming trick.

KARAN

Your poems live inside questions — and often leave them unanswered. “Where do we go from here?” you ask, before pivoting into a description of clouds, oil changes, and personal injury law ads. I love that refusal to resolve. Do you think poetry should resist the impulse to provide answers? Is uncertainty an aesthetic position for you?

CHRIS

I like uncertainty in poems and I think there are things one needs to communicate through language and metaphor that cannot be said otherwise in prose. Basically, I want to smash all the frosted windows inside words so the great mysteries of this life shine through. But as for providing answers to why we are here? I’m not sure I can do that except to say I am here, and you are here with me, and this is what I see and feel, and hopefully you see and feel some of that too. Poetry is a kind of deep empathy machine. Almost like one of the massage chairs. Sit with a poem long enough, and you always feel better.

KARAN

Let’s revisit that philosophical question and how you dress it with humor that sprouts from surreal association:

Where do we go from here? says anyone who has ever

stood at a traffic intersection with an ancient compass

buried deep inside them, beneath egos and yearning

desires, beneath shitty café art, and all those personal

injury law advertisements.

I love this kind of movement in poems a lot — you know I love Bob’s poems as I think he’s a master of this, and this is very reminiscent of his style. The raw humor with a depth of sadness beneath it; social critique meeting criticism of the self. Let’s touch on humor. I’ve read and enjoyed all your books because of wild imagination, but also the humor. Some of my favorite poets are really funny: Mary Ruefle, Dean Young, Luke Kennard, etc. What do you think is the role of humor in poetry? I ask especially because largely when people think of poetry they think of it as an expression of sadness. Of course the sadness of these poems do not escape me, but I’m sure you understand what I’m getting at.

CHRIS

Humor in poetry is always working two ways: it is saying relax, this is a poem, and we are not trying to change the world here, we are trying to tell a joke. But that is subterfuge, isn’t it? Because really, the poem deep down wants to change the world, wants to change a person, change being a kind of hope made manifest and change is so gradual, people almost miss the punchline that poetry makes change happen. I think this is what Bob Hicok does in his poetry so masterfully, and Bob has taught me a lot about humour and imagery and shifting registers just by reading him so carefully these last few decades.

KARAN

Let’s talk form for a moment. These poems are long and lush, but they never lose their energy — they pulse forward with velocity and precision. How much do you care about pacing and structure? Do your poems tend to arrive in a rush, or are they patiently sculpted? You’ve also most certainly found a voice that is yours — do you think that? Do you care about voice? If so, do you remember how you arrived at it?

CHRIS

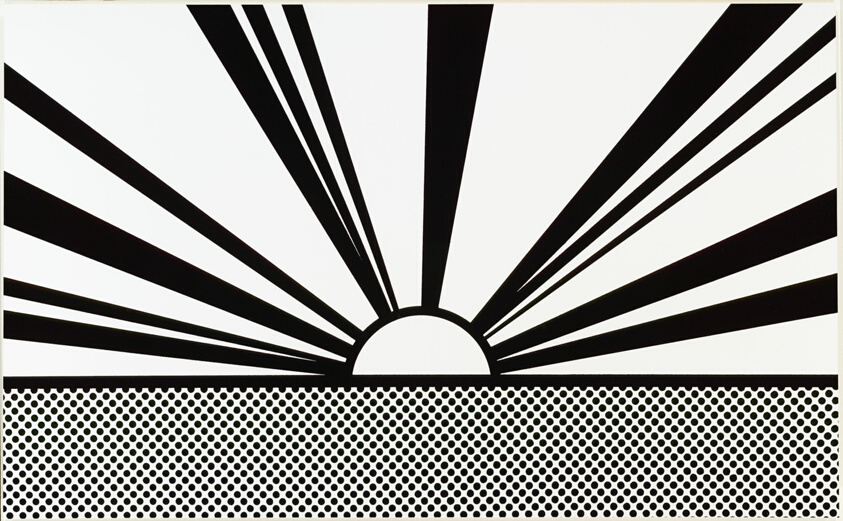

My poems arrive in a rush. The rush of the voice from within, the momentum and surge of the last line urging the next line or two into being. When I was young, I wrote very, very slowly, writing in octaves, or in narrative 7 or 10 syllable lines if you were to look at my third book Winter Cranes. My recent books have a much more frenetic energy to match the pace of our modern lives. Everyone is in a rush. We want our takeout food delivered instantaneously to our house, pics of our vacations to magically appear on our social media accounts as we are enjoying them, breaking news to be instantly communicated, etc. I am just trying to imitate with my poetic voice the speed of living in late stage digital capitalism.

KARAN

This is a recurring question for us, and I’m always moved by the range of responses: There’s a school of thought that believes a poet’s work falls into one of these four camps — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, poetry of the soul. I most certainly see your poems reaching all four. But where do you place yourself, if at all? And do you see yourself moving into a different direction?

CHRIS

I think my poems begin with poetry of the mind, but I am, at heart, a romantic, and a big softie, so although I am an atheist, I am a big believer in “soul-making” to steal a phrase from Keats. For me, the purpose of life “is to stitch a human heart” to steal another phrase from Dean Young and to do that you need to write from the body, the spirit, the heart, and the mind. You need all four to elevate your work to the point where people start noticing what you are doing.

KARAN

What is some of the best advice you’ve received throughout your writing life? And what is some advice you’d like to offer young poets?

CHRIS

Follow where the poem wants to go, even if you notice your poetic voice seems to be changing, and your subject matter is changing, even if you won that poetry chapbook contest for a collection of narrative poems, and now some inner voice is telling you to write a manuscript of surrealist aphorisms. Go where the poems are telling you to go.

KARAN

Would you offer our readers a poetry prompt — something wild, precise, or strange — to help them begin a new poem?

CHRIS

Here is one of my favorite poetry prompts I share with my students. It’s called “Living Will.” Living wills were popular in the 80s with the rise of VHS and video cameras. “The more stable the base the freer you are to fly from it in the poem,” said the American poet Richard Hugo. For this poetry exercise, the “Living Will” is our sturdy base. Look at the beginning of my poem and then mimic its structure:

To a lifetime of self-loathing , I leave this

god-hunger. To the girl I held in my arms

in the middle of winter, her boozy breath

warm against my neck, her form skipping

home through the falling snow, I leave

this scarf of regrets. To my brother who

shares my disease, a tumbler of ice and

promises. To my friends, a collection of

books and the dust of my envy.

Basically, you repeat: “To (insert any phrase), I leave…….” but instead of just family members, mention your first celebrity crush, a forest, your enemies, your boss, your kindergarten teacher, guilt, pain, awe, etc.

KARAN

We’d also love for you to recommend a piece of art — a film, an album, a painting, or even a tweet — that has haunted you lately or that you return to when the world feels especially hard to bear.

CHRIS

I’m in love with the song “The Narcissist” by Blur lately which breaks me in all the right places but I’m also a big fan of small independent films too. I would recommend the film Rudderless directed by William H. Macy. I watch it all the time.

KARAN

Finally, because we believe in studying the master’s masters, I’d love to know which poets have most shaped you — early on and lately. Who do you keep close on the shelf, or in your bloodstream?

CHRIS

The poets I have learned from the most, early on, were Philip Levine, Larry Levis, Philip Schultz, Gwendolyn MacEwen, Margaret Atwood, Stanley Plumly, Dave Smith, but recently my tastes veer towards Bob Hicok, Dean Young, Lara Egger, Kevin Connelly and Kim Addonizio. And Mark Strand and Jack Gilbert are still important poets whose voices inhabit my poetry. Honestly, I just love American and Canadian poetry so much—its given me my life—and so to list everyone who I have learned from would honestly be a monumental task.

RECOMMENDATIONS

“The Narcissist” by Blur

Rudderless directed by William H. Macy

POETRY PROMPT

Living wills were popular in the 80s with the rise of VHS and video cameras. “The more stable the base the freer you are to fly from it in the poem,” said the American poet Richard Hugo. For this poetry exercise, repeat: “To (insert any phrase), I leave…….” but instead of just family members, mention your first celebrity crush, a forest, your enemies, your boss, your kindergarten teacher, guilt, pain, awe, etc.