Death, Desire, & Belonging

On the mechanics of belonging, the nature of desire, and their expression in poetry

KARAN

Jason, I love these poems for their beguiling craft — they move seamlessly from theology to tenderness to the feral edge of grief. You balance tonal intimacy with philosophical force, and you do it without sounding like anyone else. I want to begin with “Untitled 1975–86,” which is also your ars poetica, in a way. You write: “i have failed to / mention crying here, not the tears / but actual deluge.” There’s something exact and powerful about that dichotomy — how you’re saying you’ve failed to say it while saying it. Let’s begin with the process question, Jason — what does your writing process look like — structurally, spiritually, or otherwise? And when did you come to poetry — and why poetry?

JASON

My process for writing is just trying to capture everything I think of as I think of it. Often, I will keep lines in my notes app as they come to me. I used to start all of my poems in the notes app, then once I felt like the draft was complete, I could move it to Google Docs for actual edits. It marvels me that I am able to complete poems from my phone. I started writing before there was a notes app (on my phone at least) and before Docs. I had notebooks of lyrics and poems and, to be honest, my handwriting was not the easiest to read. So, having the ability to jot my thoughts down and know they will transfer to my computer is huge. As far as the actual process, I believe it is pretty ecstatic in the sense of the tradition. I often like to write out the full picture, asking myself what is there and what is missing. This process involves me focusing on everything that is around my object. Sometimes the desire is not coming from the object in the center of the room. Sometimes the desire is a chair, I must know what I should make of that in the poem.

My first time really writing poetry was in high school; however, I didn’t truly come to the craft until late in my collegiate career. I switched majors to Creative Writing, believing I was going to be a fiction author and ended up as a poet because one of my professors told me I was a poet. I think there is beauty in the small spaces we ignore. This is why I write poems.

KARAN

“The Mechanics of Dying” is breathtaking — at once cosmic and cellular. You write: “Some call it by its god-name; fate—I just call it a murderer.” The poem grapples with mortality as both inheritance and betrayal, as prophecy and randomness. And the prose poem is such a perfect form for that poem. Do you think about poetic form as a vessel for the unspeakable?

JASON

Unless I am writing a form poem on purpose, e.g. Sonnet, Sestina, Pantoum, etc., the form of the poem is the last thing I think about. I often will put all of the words on the page before deciding what shape the page will take. That being said, just because it is last, does not mean it is not still important. Every line, space, comma, everything on the page is important and needs to be doing equally as much work as the rest of the poem. Nothing on the page should be an accident.

KARAN

This was part of my earlier question but I wanted to give it a separate room. Death seems to be one of your foremost subjects/motifs. Would you speak about that? In a sense, all poetry is about loss — of innocence, loved ones, happiness, childhood, etc, and death, in a way, is the supreme manifestation of loss. Does writing about death help you rehearse survival — or is it something else entirely?

JASON

I have a particularly strange relationship with death. When I was five, my great grandmother died and I was then introduced to impermanence. I knew I could not last forever. For a long time, this erased the fear of death for me. As I have approached death in writing, I wish to hold a conversation with them. Not in judgement or blame, but in understanding. Nothing can last forever, but can it be held off a bit longer? “The Mechanics of Dying” is a book length poem that addresses this: what happens when we see the world dying? Or when we discover disease we never knew to fear? How do we cope with death past the mourning?

KARAN

“Every Time I Start To Fall In Love With The City Again It Starts To Rain” is such an atmospheric poem — lush, cinematic, full of sorrow. But it’s also a study in ambivalence. You write: “I could leave this city— / and one day I might, but for now, I’ll catch the rain / in my mouth.” The poem feels like a love letter. Do you think of place as an emotional state? What does it mean to belong — to a city, to a person, to a lineage?

JASON

I believe belonging to a space is nuanced. I was born in Washington DC, my birth certificate states I was born in Washington DC, but I am not FROM Washington DC. I spent most of my life disclaiming my “fromness” being from Lansing, MI. I wanted to be from somewhere that felt interesting or cool to tell. To be from the DMV, but I am not. I think this dislike of my hometown created a barrier for me when it comes to loving a space. I hated Lansing until I left Lansing to move to the Ann Arbor-Ypsilanti area, then I was home every weekend. I hated Ypsi until I left Ypsi and then you could not keep me away. This is my plight of belonging to a space, it is that many of us run from the space we belong to. It is also hard for me to say I belong to a place that is not inherently mine, this comes from two different folds. I believe a place should be owned by another— what does it mean to own a land, to create a border? But secondly, I am not from, nor will I ever be, a New Yorker, no matter how long I live in this place. This is not my hometown, I am a visitor. I will never be “from” here. This disconnect forces me to feel unrooted. I am uninterested in living where I was born because that root was severed young; I am uninterested in living where I grew up, and I will never be from where I live now. These are the things I think about when writing about a place or the lineage of a place: who should love this land as home and who should love this land as a spectator to someone else’s home.

KARAN

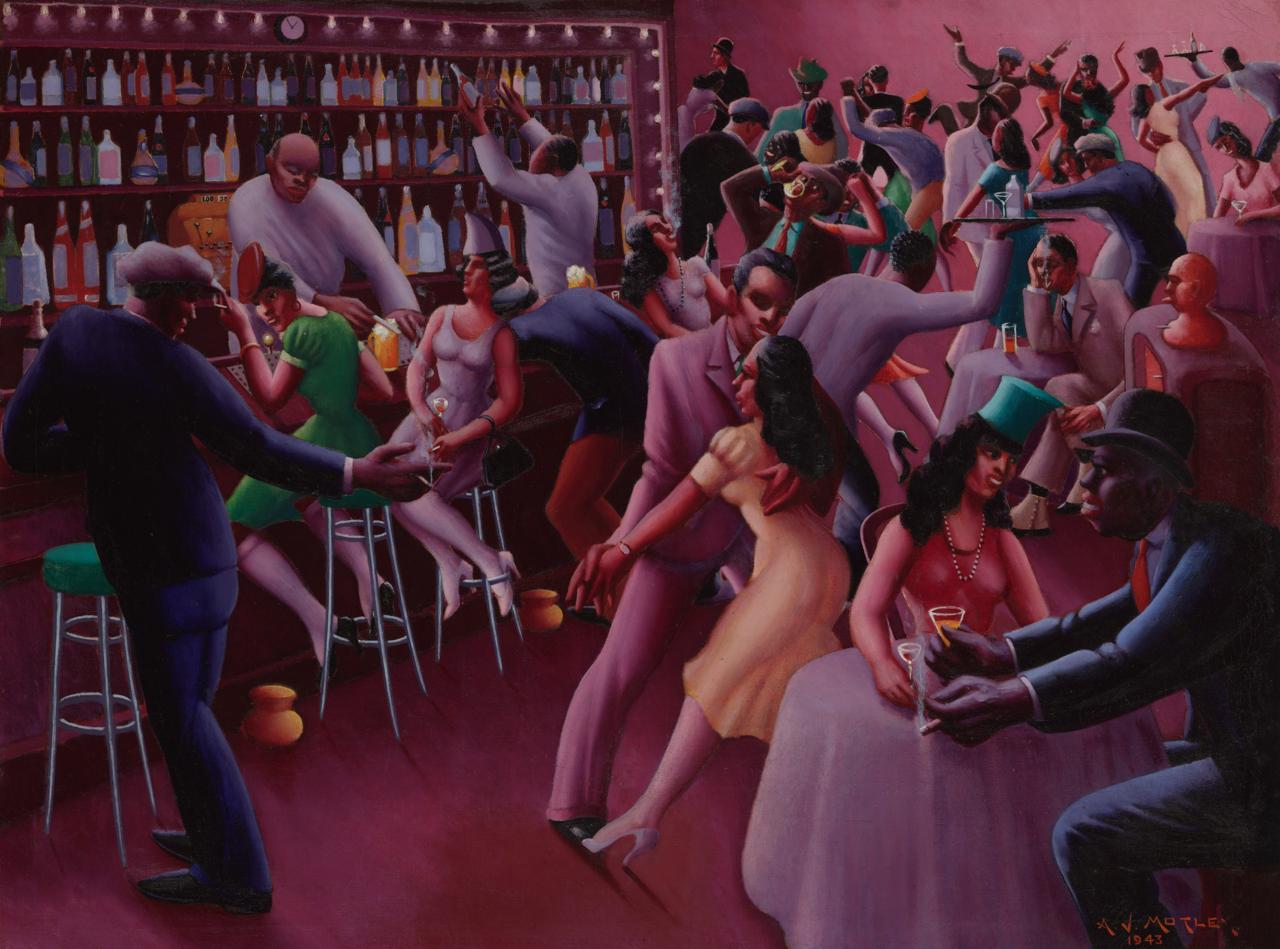

I was completely undone by “loneliness catalog: hix park” — the strangeness, the softness, and the danger of that poem. “We are all here for the same thing, but none / of us are willing to admit it.” The poem hovers between queerness and longing, but also secrecy, risk, survival. How do you think about desire in your work — especially in public or rural spaces, where danger is often ambient?

JASON

I truly believe every poem operates from a space of desire. Every poem has an object desiring something, that is not always coinciding with love or romantic feeling. That being said, the romantic or lust-filled desire appears a lot in my work. I didn’t grow up in a “rural” area. Lansing is a city but not nearly as big as Detroit or Chicago, so it still felt rural in some ways. I think desire behaves similarly but also differently between the rural space and the city space. All spaces have an opening for us to “want” the city no differently in this way, it holds desire. But the rural holds desire in a way that sometimes we are unable to fulfill. This is for many reasons. Availability, lack of interest, internalized phobia against what we want, disapproval from the surrounding audiences. I think this is why when we look at cruising culture, it is still so prevalent amongst the older queer men in rural areas. It is how they grew to understand their desire and it is the only way they know how to act out these desires. This tends to draw out danger from the others in the scene, from the surrounding law enforcement — there isn’t a part of this that doesn’t read as a risk. But being queer and having desire is a risk. This could also be why I write of desire in this way. Because I have calculated the risks and have taken them anyway.

KARAN

Let’s talk about “notice theory,” which, for me, is the most emotionally expansive poem in the set. You begin with: “i start every story with / noticing: what i can touch, / who i cannot.” (god, I love that line!) There’s a kind of spiritual surveillance in the poem — calling, texting, naming, checking the newspapers for proof of life — all forms of obsessive care sprouting from fear that is rooted in sociopolitical context. Does technology — or the anxiety of delay — shape your relationship to the elegiac?

JASON

“Notice theory” was a poem that allowed for me to vocalize my own internal monologue of how I imagined the people in my life no longer being there. When I was younger and mother was late home from work, I would often think she was dead and that would be the last time I saw her. Catastrophism is the way I have lived my life, if I think the worst, then something slightly less bad is bound to happen. With the world’s reliance on new technology to be how we receive information, I am doomed to wonder when the message of my mother’s death will come to me or how. This poem was me getting ahead of death, of technology. Or at least trying to.

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, and we love how the answers are always wildly different: There’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four major axes — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. Where would you place your work, if at all? And do you see it moving elsewhere?

JASON

I believe a lot of my work lives in the body or experiences the world through the body. I also write a lot about the body and how it often fails us. So I believe I write from the poetry of the body and I don’t really see myself moving away from that anytime soon.

KARAN

Congratulations on winning the Omnidawn book prize, Jason — tell us about YEET! Also, what advice would you give to emerging poets who are currently putting together their first collections?

JASON

Thank you, YEET! is an exploration on Afrofuturism and safety. I wanted to approach the collection with the question, what would it look like if all of the Black people on earth left to find somewhere safer, away from whiteness. It is also an exercise in Black vernacular and reclaiming, while taking on the lens of storytelling.

I would say that the biggest piece of advice I can give a writer is that we are always writing even when we do not have the pen or paper in our hands. It is so easy to get discouraged with ourselves and our work and our progress just based on if we have a collection in the world or ready for submission. Think of the process as just that, a process. Sometimes refilling your body with friendship or with sun, or with birdsong, or with beach days is the process of writing and you will get back to the poem when you get back to the poem. I think the new age accessibility to poems has forced us to think we are behind in our craft because we can see others’ announcements. You do not have to have the book ready now, it is far better to let the book be what it needs to be rather than what you rushed it to be.

KARAN

Would you offer our readers a poetry prompt to help them begin a new poem?

JASON

This might be my favorite revision prompt: Take an old poem that you wish to revise. You are going to pull out three lines: 1. The line that you like the most. 2. The line that you feel like is summing up what you were trying to say in the poem. 3. The line that you feel like has the best imagery, this should not be your favorite line. After that, you are going to start a new poem. The line that sums up the meaning of the poem is going to be your title. Your favorite line is going to be the first line of the poem. The best image is going to be a line to help you when you get stuck and need an image. Once you have completed this draft, you can either leave those lines in or take them out. I call this prompt the Bay leaf prompt.

KARAN

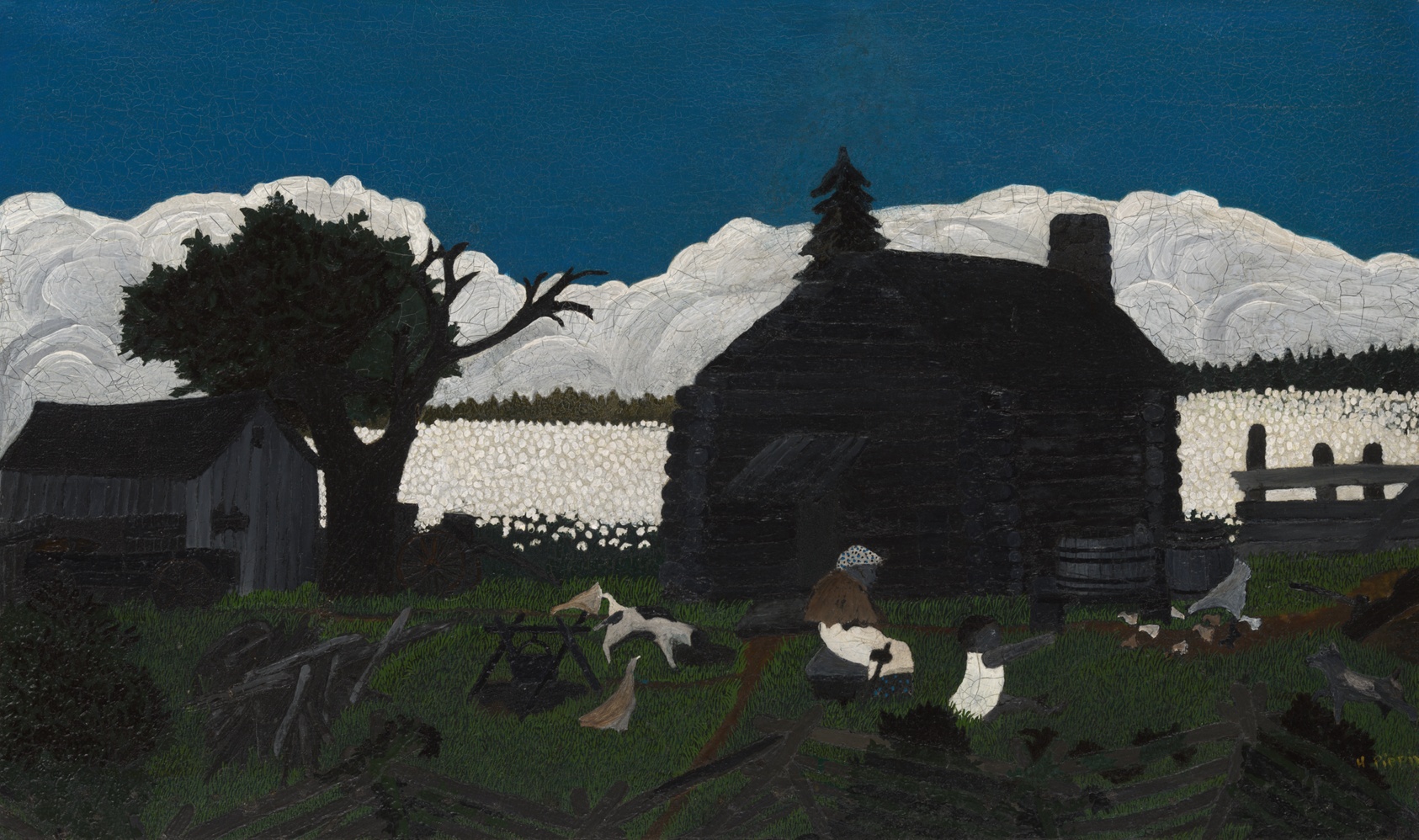

Please also recommend a piece of art (anything other than a poem) that you keep returning to — a painting, a film, a sculpture, a recipe, anything — that haunts or sustains you.

JASON

If you have not seen the work of Alvin Baltrop, you should. He was a Black, queer photographer from the Bronx that documented the piers in the 70’s and 80’s. A true testament to Limerence. The Untitled 1975-86 poem is part of a series all dedicated to his photography.

KARAN

And of course, because we believe in studying the master’s masters: who are the poets who have influenced you most?

JASON

Taylor Byas for sure is one of the best poets I have ever encountered. Danez Smith and sam sax are two people I have been learning from since undergrad me trying to string together sentences. Jim Whiteside constantly amazes me, Brittany Rogers and Ajanae Dawkins are power houses. Big love to Hanif Abdurraqib and Hieu Minh Nguyen. Patricia Smith will always be my teacher and so will Mark Bibbins.

RECOMMENDATIONS

POETRY PROMPT

Take an old poem that you wish to revise. You are going to pull out three lines: 1. The line that you like the most. 2. The line that you feel like is summing up what you were trying to say in the poem. 3. The line that you feel like has the best imagery, this should not be your favorite line. After that, you are going to start a new poem. The line that sums up the meaning of the poem is going to be your title. Your favorite line is going to be the first line of the poem. The best image is going to be a line to help you when you get stuck and need an image. Once you have completed this draft, you can either leave those lines in or take them out. I call this prompt the Bay leaf prompt.