You Are Different and Need to Be Punished

On the systemic violence of public life and the redemptive strangeness of poems

KARAN

Jason, your poems feel like dispatches from the uncanny — dream-logic worldlets that combine linguistic delight with psychic rupture. “Most of us riot / with supreme brightness” and that certainly rings true of your work. Let’s begin there. What do your poems let you say or confront that other forms (essays, conversation, work emails) do not?

JASON

Thanks, Karan, that’s lovely, and flattering of you to say. Poetry is a medium that allows us to shape language, words, thoughts, images, whatever we want in ways not possible in other forms. We can do anything we’d like in a poem, and we can express ourselves in ways we can’t elsewhere – certainly not in work emails, we’d lose our jobs. I’m drawn to the control we have as artists and creators, which doesn’t exist elsewhere in our lives. I can create a voice with which I’m more content, and which I find more affecting, than, for example, I can do in an interview.

KARAN

Your poems are often populated by strange metaphors and almost mythic figures: falconers, apostles, gym teachers with too much power, children with jackal instincts. “The Owls Beneath Our Skin” reads like a dream of Catholic boyhood and gendered dread. What does your writing process look like — structurally, emotionally, spatially? How do you begin, and how do you know when a poem’s weirdness is exactly right?

JASON

That’s a good question, and I’m not sure I can answer it. Weirdness is a reader assessment rather than something I consciously navigate. I’m just trying to write things I would find moving if I were the reader, things that feel relevant, appealing, and alluring; something with which others may connect, too; something strange, beautiful, relatable, or transcendent, with urgency and reason for existence. Whenever it feels “exactly right” is an instinct more than anything else, but who can really judge when something is exactly right, and what are the criteria?

As far as process itself, that’s more opaque. I sit down and let it tumble out of me until I nap with my cats. Then follow weeks, months, and years of revision and self-doubt.

KARAN

There’s a line in “Quarterly Reports from a Plateau”: “every time we see a pear / we must now recall / those years pressed into a wall.” That’s such a sharp rendering of trauma memory: how even fruit can get rewired by the past. These poems hold a lot of pain, often delivered in sidelong glances. What is your relationship to memory in poetry? Do you write toward clarity, or is distortion a larger part of the work?

JASON

That’s a great observation and I don’t think I write toward objective clarity, though I don’t approach poems with an intent to distort, either. Sometimes I like to eschew traditional transitions and let the readers make the leaps themselves, which can lead to more than one interpretation of a poem, letting it take on a life of its own. Memory itself is one of the biggest forces driving my creative output, if not the biggest. Everything kind of reminds me of something else, which is a blessing and a curse.

KARAN

I want to ask about humor, because these poems are also funny — deeply, darkly so. In “Most of Us Riot,” there’s the absurdity of eating the toes of porcelain dolls or declaring faith to cats via aerosol ingestion, but the joke always opens into something lonelier. What do you think humor protects in your work? What does it expose?

JASON

Truthfully, I don’t know where I’d be in life without humor. Possibly dead. On the other hand, I wouldn’t categorize these particular poems as very humorous; they address some serious, life-altering traumas. Maybe “Homage,” because it’s a memory of an argument two friends had over me while I was trying not to faint at a graphically violent art installation. But nibbling doll toes is absolutely a stimming behavior that I’ve witnessed. On the third hand, if readers are drawn to it as humorous and it draws them further into the poem, I completely support it. It can be an effective way to draw people into a poem, but usually there needs to be something more, which for me, oftentimes includes an overall sense of isolation or loneliness.

KARAN

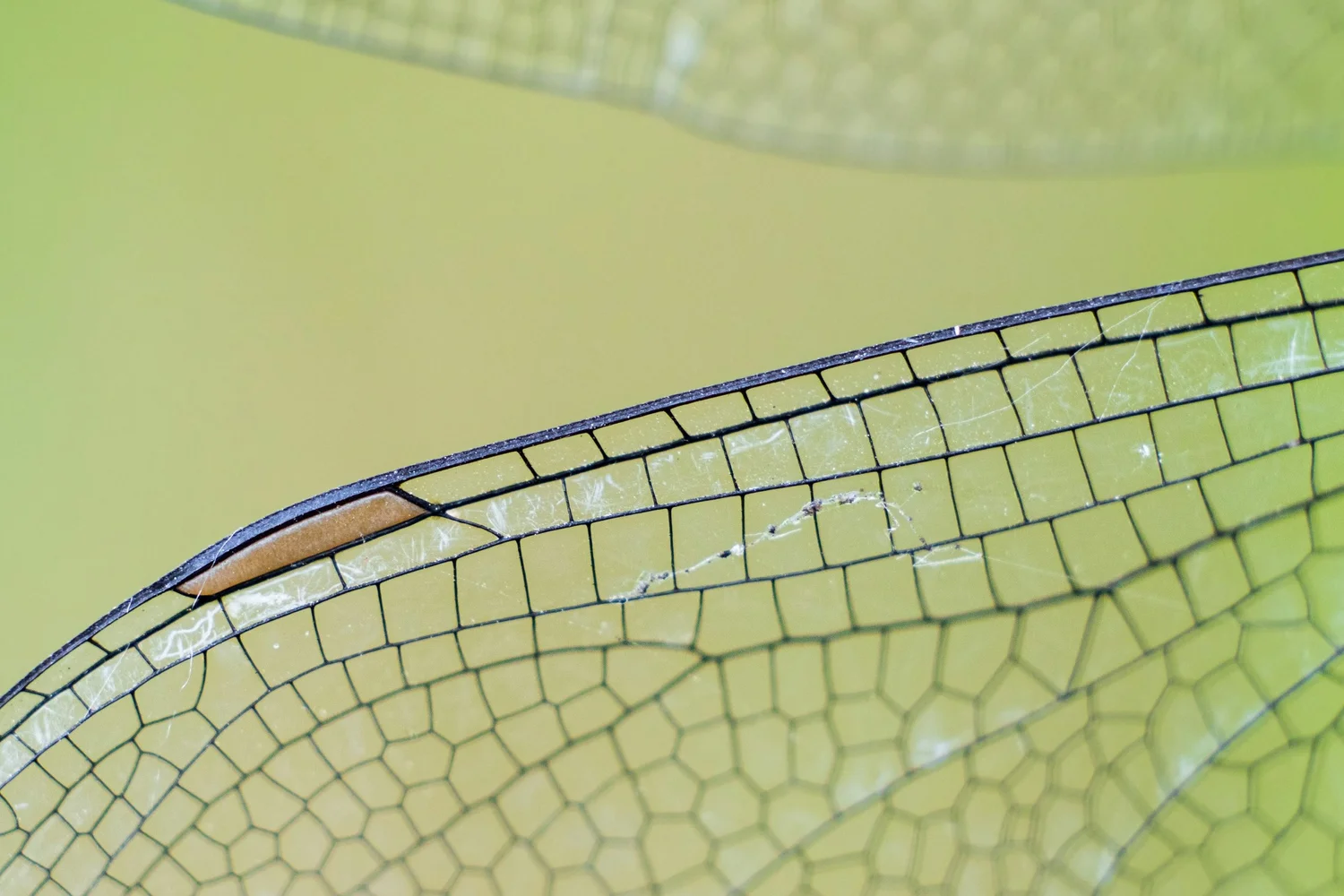

There’s a neurodivergent texture to some of the poems. “Like the Dragonfly” explicitly names stimming, teachers disturbed by “their own fictions / about mental illness.” And then elsewhere, we’re watching kids hide under cafeteria tables while principals and gym teachers become figures of systemic cruelty. You’re operating on both levels of witnessing: personal and collective. I’m not sure what I’m asking here, but maybe it’s this: how do you navigate the boundary between private pain and public violence in your work, and what do you hope readers carry away from that dual witnessing?

JASON

Yeah, the poems touch upon neurodivergence like I hadn’t done before, rather than hiding it. Truthfully, I’m diagnosed with ASD and masked it my entire life. My son is diagnosed with ASD and was victimized with some intense physical and emotional abuse by teachers, administrators and peers at his public school district for a couple of years as my mother was dying. The school district called him an “expressionless, non-functional shell of a boy with no friends, no hope, and no future” during due process. All because he was unfortunate enough to be like me. It was an extended period of misery for me personally and created an urgency for the poems because it’s important to me to address the experience. Public education, the legal system, public discourse, all of it is so unforgiving to people who are different. For most of my life I thought it was just me, that whatever pain I held onto was because I was wrong or too sensitive, but after connecting with others who’ve had similar experiences, I understand it’s systemic in this country. The public discourse generally dismisses listening, empathy and thoughtfulness for uneducated didacticism. “You are different and need to be punished until you change,” as if “being different” isn’t punishment enough sometimes.

KARAN

I keep returning to that image in “Dreams” — a group of impatient falconers trying to dream of fairies, failing. There’s a longing for spiritual feeling in your poems that really appeals to me, especially as it sits alongside a deep suspicion of organized belief. “Homage” uses a gunshot as a kind of ritual. “Blackbirds” might as well be a funeral dirge (though for something ongoing). Are all poems of grief? And what takes the place of faith?

JASON

I like that observation, and “Dreams” is one of my favorites because it’s such a succinct glimpse into being me. It’s also one of those poems that just tumbled out of me. But no, I don’t think all poems are of grief, or all of my poems, and I don’t know what takes the place of faith, maybe that’s in part what drives poems, or these poems, and probably that poem.

KARAN

There’s something post-apocalyptic and intensely Now in these poems — corporate language, reports from plateaus, teachers filing civil cases, the violence of “god’s house already in foreclosure.” You gracefully negotiate between being satirical and sincere, something I think a lot of writers struggle with. When you’re writing, do you feel more like you’re slipping into a mask of satire, or stripping one away toward sincerity? Maybe it isn’t one or the other?

JASON

Thanks. Occasionally I’ll write satire, which I enjoy, but I wouldn’t categorize these poems as particularly satirical, and I’m not sure that satire is a mask. Its goal is to expose and generate criticism. If anything, corporate language is all around me so it’s easy to absorb. It can also be a good prompt. I’m afraid I’m not good at answering this question. When I’m writing, I’m not thinking about how to be sincere, because that in itself seems insincere. The poems are just a reflection of me and what I’m like inside.

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, though the answers are always wildly different: There’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four major axes — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. Where would you place your work, if at all? And do you feel it shifting?

JASON

Haven’t heard that before but I like it. Poetry of the heart. I think it’s always been that way.

KARAN

I like the title of your forthcoming book a lot: I Love You But I Don’t Speak Your Language. It hints at love poems and hints at lamentations. That paradox runs through these poems here. Tell us about that book. And it’s your ninth! — how is it different from your other collections? (This last one sounds so stupid so feel free to change/interpret it however you like!)

JASON

Yeah, the title is an expression that seems to have defined my life. The poems in that collection are overall a bit more absurd and humorous, but the undercurrent of loneliness and isolation remains. They are more “I did this, and I did that” than these poems.

KARAN

Congratulations, too, on the Juniper Prize! What advice would you offer young writers? Lay it all on us.

JASON

If you can bear it, don’t give up. It took 14 years to publish that collection and it wasn’t because I wasn’t trying.

KARAN

Would you kindly offer our readers a poetry prompt (something strange, simple, or rigorous) to help them begin a new poem?

JASON

This is so hard. I’m in need of prompts myself. Start with a line from something else? An article, a song, something you overhear someone else say? Corporate language is good, like I already mentioned.

KARAN

Please also recommend a piece of art — a film, a painting, a song (anything other than a poem) — that’s sustained you lately or that you wish everyone would sit with.

JASON

Celer: It Would Have, But It Wasn’t; Gems; The Once Emptiness of Our Hearts; Para; Sunlir, The Everything and the Nothing

KARAN

And finally, Jason, since we believe in studying masters’ masters, who are the poets that have shaped your sense of what’s possible in language, your strongest influences?

JASON

James Tate, John Ashbery, Ted Berrigan, Anne Carson, Tomaž Šalamun. Not poets, but Jean Rhys, Nabokov, J.M. Coetzee, and George Saunders are inspirations, as well.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Celer: It Would Have, But It Wasn’t; Gems; The Once Emptiness of Our Hearts; Para; Sunlir, The Everything and the Nothing

POETRY PROMPT

Start with a line from something else? An article, a song, something you overhear someone else say? Corporate language is good, like I already mentioned.