Canonising Faith: Every Poem is a Homily

Ramsey Tawfick talks about Leonard Cohen, religion, and the way faith shapes poetry

KARAN

Ramsey, these poems feel ancient and futuristic at once — devotional but suspicious of devotion, reverent & irreverent in the most delightful of ways. I kept thinking: this is theology re-engineered through the supermarket, through capitalism’s graveyard of signs. “A church is any 2 who meet within me” is just brilliant (and what a title!). You’re writing toward origin and fracture — the mother as church, the obelisk as language, the body as translation. There’s a lineage of myth here, but the poem feels newly made — simultaneously a prayer and an expression of grief. Let’s start there. What does the word faith mean to you?

RAMSEY

Thank you so much Karan, that's a beautiful way of looking at my work! I oscillate around faith, I am very interested in its aesthetics and movements. I think, like a lot of people, I am still determining its function, and these poems feel like starting at the end and working my way back to creation.

To me, faith and spirituality are different registers; faith is the observation of the divine and what and why your spirit moves are beyond both your body and your control. So, in a way I am trying to decide what is worth annotating, tracing my own historical and religious continuity and trying to make something new, something I can speak of even if its boundaries are not fully clear to me yet.

That being said, I am extremely suspicious of religion, he's the weird uncle shouting at you at dinner telling you what to eat and why. So, when I speak about the church, I mean the primordial body, the mother, when I speak about the priest it's a criticism not a confirmation. It's not an anti-religious attack, at least the poem you mentioned isn't supposed to be, it’s more a rewiring of the circuits, taking what works about faith and bringing it closer to the spirit with the hopes it’s viewed as an act of service rather than dissent.

KARAN

What does your writing process look like, Ramsey — structurally, emotionally, spatially? How do you go about building poems that move between monument and intimacy without collapsing either?

RAMSEY

I am a big believer in the notes app poem, most of my work starts there, and then develops and transfigures onto the page. There is something religious about my structure, I grew up praying the rosary, going to church and generally surviving catholic incantations, and so I have to assume some sort of osmosis happened, where the rhythms of prayer became part of how I write.

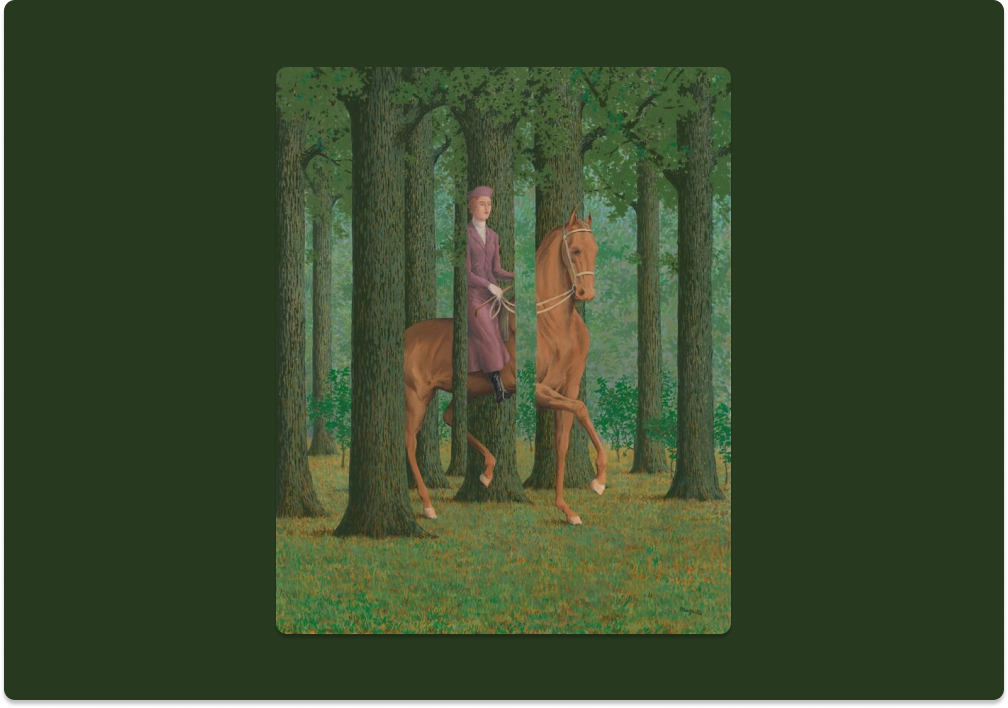

Writing to or for the site of monument has its own sort of intimacy, the poem a church is any 2, was written half in Italy and half in London, when I noticed that an obelisk was always placed in the centre of a town or city. In London, there’s an obelisk on the embankment called Cleopatra's needle, which Sabrina Mahfouz's book These Bodies of Water first directed me to.

Mahfouz views the needle's journey to London as parallel to hers, it was originally a gift from Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1819, to thank Britain for their help in winning the Battle of the Nile and the battle of Alexandria, but while it was being transported it got lost at sea, eventually washing up on British shores about 60 years later. Its cultural and historical recording is the immigrant story; it’s part of our journeys as much as the people we arrive with are. Opening myself up to the possibility that diaspora includes the artefact puts me in conversation with the world, it opened up my writing space and now I see an obelisk wherever I go.

KARAN

“Jesus for the Shareholders” is devastating — a sermon rewritten as a corporate memo. You take scripture’s moral language and infect it with the syntax of extraction: “That your bankrupt business is salvaged and bolstered / again and again / so your golden towers can be erected / on top of the chapel doors.” What power do you think poetry has to intervene in political systems? How does poetry & politics interact for you?

RAMSEY

Poetry is inherently political; there’s not enough money changing hands for it to be anything else. This poem came right after Trump's re-election and his violent and immediate attacks on the autonomy of women and their bodies. I was angry as a lot of us where, but political degradation isn't new, religion usurped for attack and control is an even older tactic, and so I wanted to reconfigure the language of the attacker to represent both.

That being said, I'm not sure the poem or poetry itself can claim political activism. Poetry is not the change directly. Juliana Sphar says poetry accompanies activism, it’s the 'riot dog' at the protest, barking and spurring people on. I view it more as a signifier of change, the 'poet of the picket line' needs to write about the world around them in a way that makes movement but not be deluded enough to think that this alone can be their contribution, or at least that's how I look at it to hold myself accountable.

KARAN

Your poems are full of invented scripture, a sort of sacred remixing. They borrow the rhythm and syntax of biblical speech, but the tone feels postlapsarian, exiled, aware of its own loss of innocence. Do you see poetry as a continuation of that sacred voice, or as a rebellion against it?

RAMSEY

This would be an easier question to answer if I was more affirmed in my faith or non-faith, but the biblical tones of my poetry do come from an archival voice, a sort of reimagining of scripture as it exists to us, after the fact, signifying the end of times or the beginnings of something new. I find my way back to the sacred voice by accident, I stumble into it like the rosary so I haven't decided if I am rebelling or affirming but I do think the answer will end up being a bit of both. I think poetry has the ability to reach the divine, what you do from there matters less than the journey, I think in a lot of ways I am substituting prayer with writing, so I am less concerned with attacking or continuing the sacred voice and just want to try my best to locate it in the world around me.

KARAN

In “Proto deities,” faith is presented as an accident — “the hunter-gatherer raises a rock to the sky / for no particular reason.” I love that line: belief as a misinterpretation, the divine as misunderstanding. What draws you to those first myths — the origins of worship, of making, of naming?

RAMSEY

Not everyone will agree with me, and I mean this with love: I am drawn to these myths because they're ridiculous and self-aggrandizing; they make mountains out of molehills in a way that’s both comical and spiritual. I think spirituality is an accident the same way our existence on this planet is an accident, it’s a beautiful mistake but claiming we were owed it or that we forged it with hindsight is exactly how we ended up with the Swiss guard wearing those crazy outfits.

If you look at the Abrahamic religions the prescription of religion comes out of a need to canonise the actions of regular people. Christianity especially, the New Testament is the signifying of one man’s good and kind actions as holy. I do view goodness and holiness as something we have to work towards, something that has an origin and a myth. But we sort of failed upwards into it and some people find its continuity in scripture and some people need something more. My mother is a devout Catholic. It helps her build community. It keeps her moral and kind, but we argue over sanctity a lot, because prescribing origin and naming goodness as a form of worship can distract you from the fact that there is absolutely no certainty in our sacred myths.

There are also too many calculated and sinister forces using worship and naming to control and dominate others, and that’s where I think we have to put our hands up and say none of this makes sense, but we can still be good anyways. Lets still pray and canonise our faith because we're people, that’s what we do and it doesn't have to be any bigger than that.

KARAN

I’m fascinated by how your poems use inheritance — biblical, maternal, artistic — and then rewire it. I sense the Coptic-Egyptian imagination of faith, but also a distinctly British cynicism about empire and industry. How do you navigate those crossings of geography? And how does being British-Egyptian shape, if at all, the way you approach the English language itself?

RAMSEY

Thank you for this question, it's something I spend a lot of time thinking about and feel very conflicted about. I think it would be wrong on many levels for me to speak with either voice as an absolute authority. I am not smart enough or experienced enough to be the cultural archivist who speaks for Christian Egypt and in the same breath I'm not British enough to claim that voice either.

I am a diasporic writer, it’s something I take a lot of pride in, but it was a long and personal process to make peace with myself. For a lot of us, it’s difficult to determine when crossing over the geography of your cultures is a betrayal or overstep, you are kind of pigeonholed into feeling like you are made of two halves. But I am starting to believe that I am just one person, made of one self, hitchhiking on different cultural highways and I'm focusing on enjoying the ride. I want to/have started to use language without having to worry about balancing who I speak for and that’s very exciting. It’s new and unburdened and requires you to let go of the voice telling you to Anglify or Egyptify yourself to appease anyone else.

KARAN

“I too, would have been Leonard Cohen if it were not for the supermarket” is a masterpiece of both irony and despair. It’s a poem about poetry as much as it’s about consumption. “Love in the time of quantities,” you call it. What’s your relationship to irony and sincerity — and do you think contemporary poets (especially those writing inside capitalism) can ever really separate the two?

RAMSEY

What a great question, I don't think we have a choice anymore right? That poem is as much a love letter to Cohen as it's a memo letting him know that we fucked it all up. I think irony is an easy way to not cry at that sentiment, it’s your best bet to shield yourself from reality, and it’s been the register of our cultural conversation for as long as I have actively participated in it. But I do want to be more sincere, both as a poet and a person because it’s a lot braver to be open and love something than to pick another thing apart.

I recently became an English teacher, and I've noticed kids detach themselves quite early. They are scared of being sincere and unbridled, loving something in the open, and I don't think it’s just them, we’re all guilty of it as well. But these protections won't hold, we're in the post irony phase: irony doesn't work anymore because everything ridiculous and horrible is feasible and I think I'm trying to get the kids at school and in a larger sense myself to be comfortable with being cringey, with being authentic and not detaching because you’re scared if you reveal the things you care about someone will take them away or worse try to monetise them.

KARAN

You were longlisted for the Leonard Cohen Prize, and there’s something Cohen-like in your register — the fusion of sermon, blues, and apocalypse. And I know you share my obsession with Leonard Cohen — tell us why his work appeals to you? When did you first encounter it? Why does he occupy your brainspace the way he does?

RAMSEY

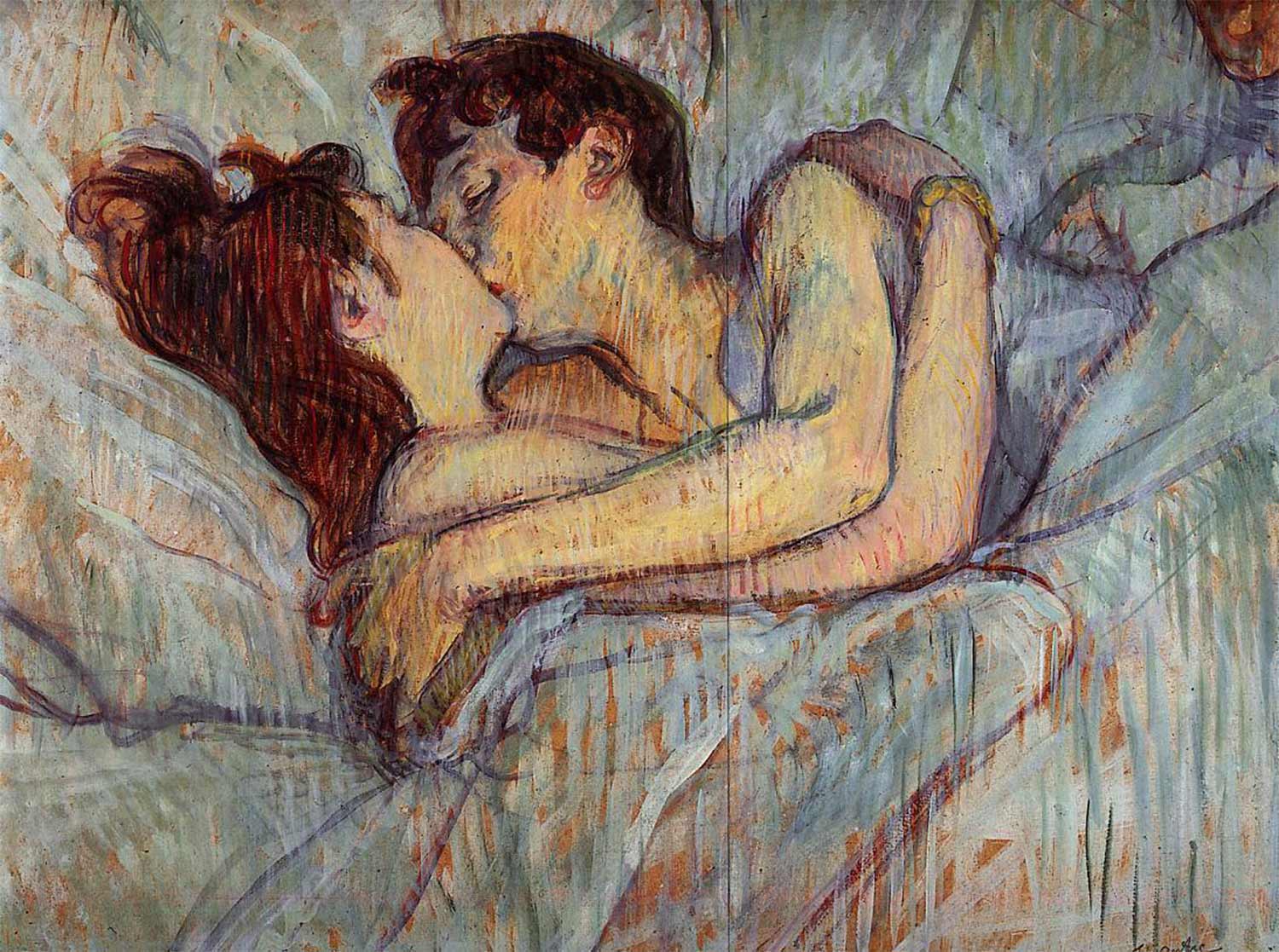

God, Cohen has been the backing track to my life for as long as I can remember. My dad loaded the album Various Positions into my iPod when I was about 13 years old and Cohen's voice hasn’t left me since. He blends faith, spirituality, and sex in a way that makes new religions. Every song is a sermon, whether on purpose or by accident and every poem is a homily.

We spoke about how his register is infectious, how you listen to him and might accidently find yourself writing as him. The poem I wrote to him was an attempt to lament the fact that the systems of capital over consumption make it hard to locate him anymore. When you look at his music, his most "culturally attractive" or noted work comes out in other people’s voices. But I know he was secure in this fact, that he didn't want to be remembered and quite honestly, he didn’t seem to care. I aspire to not define myself the way he managed to, I also never stop listening to his music and I don't think I ever will.

KARAN

The closing poems — especially “the last man on earth” sequence — are eerie and tender. A creation story in reverse. God is gone, history’s gone, and the last human makes a sandwich, then writes poetry. It’s funny, and somehow holy. What does that image mean for you — art after the end of the world? What’s left when there’s no one left to read?

RAMSEY

I think of the last man on earth in that poem as both a problem and solution for the new world. He is by himself and all he knows is consumption. With nothing left to do he eats and forages and has this sort of physiological collapse back towards our beginnings, but he is also the way forward, poetry without audience, history without archive. You’re right that there’s a holiness or scripture-like affect there. I don’t think I intended it but a sort of accidental declaration of post faith.

The last man on earth reaches enlightenment because there is no audience left to hear his declaration of faith. He achieves a clean spiritual presence, but he fails to use it and returns to the consumption we have been taught to embed into our faith. I think both as poets and people we are taught how to perform constantly, to act for a series of invisible audiences and the poem was me imagining the internal apocalypse that would happen if there were no more stages to stand on. I don't think he's content or happy, I think of him more as an affirmation that even when there is no one left, we have to put in the time, we'll still make art even if there is no one left to applaud us.

I was also making a sandwich when writing the poem and thought it was quite a funny juxtaposition, so I guess beyond any sort of spiritual reclamation I may have just been really hungry that night.

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, though the answers are always wildly different: There’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four major axes — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. Where would you place your work, if at all? And do you feel it moving elsewhere?

RAMSEY

Honestly, based on how great your questions are I think you would be better suited to answering this question. I know why I write a poem after the fact, I don't tend to build up to one with any expectation so it's hard to say if I have an ethos or an overarching theme. I view all four of these axes as part of a larger tapestry, so I am sure some poems lean more into one than the others but also these categories lean towards the self. I am desperately trying to claw away from the self in poetry, I want to record how cultural currents move through people, I said earlier I didn't want to be a cultural archivist, but I want to notate something new, something people with less rigid definitions of country and identity are struggling towards. I would love to step outside of myself more, I wrote a poem from my mother's perspective once, while she relayed her memories of Cairo to me, and the joy we shared when it was finished was more rewarding than any publication of my own work. So, if I were to say I was building towards something it would be poetry of community.

KARAN

Ramsey, what’s the best piece of writing or art-related advice you’ve so far received that’s influenced either your craft or process or both?

RAMSEY

Bob Dylan said something along the lines of he didn't know/care where his music came from, he just sort of stumbled into the truth and knew he would only be there for a short time. I like the idea that you go somewhere else and you can never really hold it for long enough to make sense of it. I try to remember that whenever I am putting too much stake into being a poet or writing, it’s all smoke and dust anyways, so now I am trying to just enjoy it while it lasts.

Something that also sticks in my head is the fact that Billy Joel stopped writing music in 2001 because he wanted to live instead of being an artist. He realised he wasn't going to be as good as he once was and made peace with that. He still performs loads and has only slowed down because of some health issues but I love the idea that you can force yourself to stop and just enjoy the ride at some point.

I can also tell you the worst piece of advice I ever got, which was to write more about pyramids to really solidify my “whole Egypt thing.”

KARAN

Would you kindly offer our readers a poetry prompt — something strange, simple, or rigorous — to help them begin a new poem?

RAMSEY

Think about your childhood home, think 1000 years from now, imagine the archivist or archaeologist notating its smells, what it looks like, what ghosts still linger. Write the site from their perspective.

KARAN

And finally, Ramsey, since we believe in studying masters’ masters — who are the poets or prophets or lyric architects that have most shaped your sense of what’s possible?

RAMSEY

Well Cohen (Obviously) but I am also trying to trace a trajectory of Arabic writers who lean more experimental or are exciting outside of their traditions. It’s a very underrepresented space—not that there aren't loads of incredible writers but that they're all sort of scattered. Five people who inspire me endlessly and whose work you should read are Sabrina Mahfouz, Etel Adnan, Safaa Fathy, Matthew Shenoda and Marwa Helal.

I think my palette also developed from music. I never want to give my dad credit but if he hadn't introduced me to Cohen, Simon and Garfunkel, Jacques Brel and Abdel Halim Hafez, I probably wouldn't be writing today.

I also owe a lot to Francis de Lima, who changed the way I think about the written page and is just generally responsible for me understanding more about poetry and the poets who expand what's possible. And without my MA and Undergrad professors Will Montgomery and Redell Olsen I would not have developed a deliberate and experimental practice. I also collaborate on films with my brother Freddie Tawfick, who is an incredible photographer who can visualise the themes I explore in a stunning (and much more profitable) way.

More importantly than artists, than the poets I have read or musicians I listen to, is my partner Gina who keeps me grounded in all of this. Without her it wouldn't matter who inspires me because I wouldn’t be able to make sense of the world. She expands what is possible, both for my writing and my life.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Youssef Chahine’s An Egyptian Story is my go-to for anyone interested in films or learning more about Egypt’s cultural history. It's also just a really great film.

POETRY PROMPT

Think about your childhood home, think 1000 years from now, imagine the archivist or archaeologist notating its smells, what it looks like, what ghosts still linger. Write the site from their perspective.