A Hole in the Sky and We Call It the Moon

On survival, suspicion, poetic reconstruction, and approaching change as a deliberate practice

KARAN

Richard, thank you for your magnificent book — I had a great time reading it. I feel like I know you/your life a lot better than I did with the earlier two books, and though that doesn’t necessarily have to be a good thing, it certainly is in this case. Let’s start with prose poems — I’m a lover of prose poems and was delighted to see that this book is essentially a book of prose poems, and you’ve mastered the tango between narrative and lyric that the form allows. These prose poems double as argument, anecdote, fable, and confession. In the final section of the book, in “Paragraph,” you touch on some of this: “I set the margins and surrounded the thoughts on all sides. I made everything the same shape and concentrated on the space between the thoughts.” What drew you to prose poems? In a sense you’ve moved dramatically in terms of the look of poems — from a lot of movement on the page to walls of text. Did prose blocks offer a new kind of architecture for your voice — or simply a better hiding place? I read in another interview that after the stroke, you didn’t know how to break a line any more, though I refuse to believe that.

RICHARD

There was so much disjunction in my life, I didn’t dare break the line. I didn’t dare break anything. The goal was cohesion, reconstruction. The challenge of recovery was to master the space between the sentences. To latch the sentences together. There was so much associative leaping, I needed a container. I want to have a different form for each book. I didn’t realize it would be this form at first. Crush has indented lines, War of the Foxes has left-justified lines. This book works in paragraphs. Crush follows the voice, is scored for breath the way music is scored. This book is meditative. It traces the path of a mind. So yes, a new architecture.

KARAN

There are a lot of purely delightful moments in this book where your imagination has me in awe. “A boy on a trampoline goes up and down, up and down in his invisible elevator. He is learning how to think about it. He is learning how to feel about it. His face is a newspaper. His heart is sweet candy.” There’s so much tenderness here, too. Also thinking of this moment in “Cult Leader”: “Damaged people would sit on the couch and unload their emotional problems all over themselves. At night, I would unfold the couch and sleep in it.” Ah! How important is imagination for you when it comes to poetry? Poetry, interestingly, sits at the cusp of fiction and nonfiction. Did it happen? Maybe. Is it true? Yes. Me, I cringe at the tyranny of fact. And though in a sense, I Do Know Some Things is full of facts/factual retelling, they are constantly elevated by imagination or philosophy.

RICHARD

In “Cloud Factory,” I say “Imagination—image is the coal that fuels its little engines. Shovel coal. Call it love, call it a day’s work.” I lost the line break when I chose the prose poem form. I lost metaphor when I decided to tell the truth and decline artifice. The image had to do the work instead of metaphor. This poem is one of the few places where I allowed myself to use metaphor, and that’s because it’s about making metaphors. The workers in the cloud factory are there to create an opportunity for associations. “They made some shapes so we could guess. We looked at them. I did. Meaning comes from somewhere.” Imagination causes problems, though. Speaking in figurative language with the doctors didn’t work. They didn’t try to understand. They ignored some very important things I was saying. I just wasn’t able to say everything literally. Everything in this book happened. I tried to be as accurate as possible. If I lied, I would be constructing an inauthentic self.

KARAN

You’ve said in past interviews that Crush balanced feeling with lyric, and War of the Foxes balanced anger with fable. These new poems feel flooded with thinking and remembering — argument, analysis, repetition. What happens when the lyric voice gets replaced with something closer to an interior philosopher? Or a prosecutor?

RICHARD

Refusing the lyric gesture is very dangerous. I consider myself a lyric poet. The stroke left me with half my body paralyzed. Refusing the lyric left me with half of my skill set paralyzed. But these are not poems of song. I didn’t want to be in my damaged body. I wanted a life, and a poetry, of the mind. I wouldn’t fill my lungs. I wouldn’t let myself resonate with sound. It was unpleasant. It was conceptually disgusting. In “The Horns,” I say “The body: I’m insulted by the physicality of it.” The line break is part of the lyric gesture. You can’t sing without a body. I didn’t have a body, not a reliable one.

KARAN

Your poems often seem to know they’re being watched — they look back at the reader. In “Dinosaur:” “Once you look something in the face it starts to want things.” What do you make of that dynamic of witness and refusal — especially when the “thing” you’re looking at is your own pain?

RICHARD

Even in a simple poem, where a speaker is addressing a lover, the author knows they are being overheard. You always know there’s a reader. The reader turns every love poem into a love triangle. Even in the poems where the speaker is struggling to be understood by others, the author knows that the reader is there with the best intentions, leaning in very closely, trying to understand. Even when a speaker is speaking to themselves, they are making a document for a future reader. I like to push against the fact of that, sometimes even addressing the reader directly. In War of the Foxes, I hid in the personas of others—of birds, fishsticks, the moon—and addressed the reader from there. It gave me a greater range to speak from. Conversely, there are places in my books where I tell the reader that I’m not going to tell them everything.

KARAN

You’ve said elsewhere that the poem belongs to the reader once you’ve written it — I’m curious: do you think about the reader as you write? Is it an ideal reader, or a general mass of imagined people, or no-one? Is it a good idea to think of a reader as you’re writing? What are the pitfalls?

RICHARD

I think it helps to have a specific reader in mind. An intimate one, even if an imaginary one. You shape your language to be understood by a specific target, and you use specific strategies to reach them. If the intended reader is your mom, you will make some choices. If the intended reader is an enemy, you will make some choices. Politicians and reporters aim for a general public at a middle distance. They sound different than poets. I like to vary the people I’m talking to, the direction of address, but I’m usually speaking to one person at a time.

KARAN

You’ve always been a poet of lists: of injuries, lovers, metaphors, commands, facts. I’m thinking especially of “History:” “Stevens had a blackbird. Stein had a rose. Thor had a hammer. He hammered in the morning.” That is funny. (We should also talk about humor.) You’re building momentum through addition/repetition, and movement through association, as in “Cloud Factory,” that I dig. Crush had its own litanies, which often felt incantatory or obsessive. What keeps drawing you to the list as a formal engine?

RICHARD

I try to be very considered in my craft choices, but sometimes style is just evidence of the shape you are. I think in lists. I make lists. I think it works for me, and if it didn’t I would still be drawn to lists but I would have to constantly fight the impulse. I also think in units, in batches. I can’t imagine putting out a gathering of poems. Each book has a shape in my head. I can’t imagine publishing a “Selected Poems.”

And yes, let’s talk about humor. Humor’s another strategy. It’s one of the best ways to undercut authority. Sarcasm and satire are useful but often negative. (I use them, though. I try to use everything.) And irony can be smug. I’ve been trying to use humor to point out the absurd. It’s more flexible that way, and can be filled with dread or wonder. The world is terrifyingly funny. We have to address that, too.

KARAN

“Identity is self-defense,” you write. “I told myself a story about myself and bought some time.” There’s a tug-of-war here between sincerity and constructedness — the need to mean it and the simultaneous awareness that meaning is staged. Do you still believe in the possibility of honest storytelling? Or is everything a tactic?

RICHARD

Metamodernism: It’s characterized by an oscillation between seemingly opposing forces like enthusiasm and irony, sincerity and self-awareness. It’s not so much a tactic as a paradigm. Meaning can be both staged and honest. In some sense, meaning is staged on a foundational level. All language is staged; all sentences are speech acts. Similarly, all actions—even walking—are choreographed to some extent. Practice and intentionality are needed. When I was relearning how to walk, I was constantly falling down on the padded mat. It took a lot of focused attention to get one foot in front of the other.

KARAN

“Landmark,” ends unforgettably: “I dug a hole in the sky and called it the moon. A hole in the sky and we call it the moon” Elsewhere, you describe identity as self-defense, narration as noise, and language as architecture that might still collapse. The poems keep staging little acts of naming — not to solidify the world, but maybe to buy time inside it. Do you still trust the act of naming? Or does it feel, more and more, like painting a fire escape on a wall and calling it a door?

RICHARD

I refused naming in my first two books. I described, I evoked. I never used the words “longing” or “panic.” Often, when I used a naming term, I would subvert it almost immediately. This book is a glossary, a compilation of encyclopedia entries I used to triangulate a truth in an attempt to define myself. Each poem is an attempt to describe what I mean when I use the term of the title. In “The List” I say “I made a list, a working glossary. My handwriting was big and crooked. Meat. Blood. Floor. Thunder. I tried to understand what these things were and how I was related to them. Doorknob. Cardboard. Thermostat. Agriculture. I understood north but I struggled with left.” And yet, even with an extreme focus on definition, the poems swerve and self-erase. They complicate and contradict. It’s not that definitions are inaccurate, it’s that they’re incomplete.

KARAN

In this interview from a decade ago, you said painting allowed you to commit to imagination “without being called a liar.” The new poems, though, seem to double down on that tension — they’re full of traps: optical illusions, logical fallacies, cinematic edits. Have you been painting since your recovery? Has visual art made you more suspicious of language’s performance?

RICHARD

Style is how you compensate for what you can’t do. My hand was shaky and clumsy after the stroke. I had to develop a looser style. I had to make things without relying on the precise gestures I had been using. All my gestures have changed, in painting and in poetry, in conversation, even in the way I move my body. I limp now, I have a clumsy arm. My physical gestures have changes, not just my craft gestures. I think both poetry and painting deal with representation, with approximation. They are equally suspicious. Poetry isn’t nonfiction. Poetry uses the language of conversation for not-conversation. It’s the same material, so it’s easy to forget that it’s heightened and framed, that it’s crafted to inspire you to feel or think or act. The painted bowl of soup will not satisfy your physical hunger. The painted bowl of soup is there to satisfy your painted hunger.

KARAN

There’s an aphoristic rhythm that pulses through your poems: “Regret is a version of yearning.” Or “Style is how you compensate for what you can’t do.” Or “The beginning of a story is a dangerous place. Anything can happen.” And my favorite: “We have to practice losing everything. We are deer, we are headlights. We are the road where they collide.”

I’m a big fan of the aphorists. At the beginning of this year we featured James Richardson whose essay on the aphorism I revisit often. I guess I’m about to ask the age-old process question: how do your poems take shape? Do you begin with an image, a line, a memory? And do they come to you more or less fully-formed? Are you a slow writer or a fast writer? Do you revise a lot?

RICHARD

An aphorism—a strong, declarative statement—is a way to gain closure. It clicks shut. When you make an associative leap you have to have a solid landing. You can’t jump into the air and then jump again from midair. Attempting it produces unfollowable abstractions. That can be interesting, but that has to be your project. If that’s not your goal, the gesture works against you. As for the question “How do your poems take shape?” I’m going to scold you. I don’t repeat myself. I don’t construct out of habit. I don’t begin in a certain way. Sometimes I am fast, sometimes slow. The question “How did this poem take shape?” can be useful. “How do your poems take shape?” is unanswerable. Well, if it’s answerable then the poet is lazy and uninspired, and their work will get boring and repetitive after a while because the poet is refusing to grow. One true thing I can say about my work in general is that I revise a lot. I think the magic happens in revision. I think it’s vain to think you’ll get magic on the first try. Certainly you can’t do it every time. You can’t rely on it.

KARAN

Several poems here circle solitude: “Why is it we believe we only have one soul? Because it’s easier to set the table for one. And you can sing your dinner tune to yourself while you eat over the sink.” Throughout the book, there’s a kind of loneliness that doesn’t ask to be solved. Do you think of these as lonely poems? Is loneliness your overarching subject, the way solitude was Garcia-Marquez’s, or futility was Beckett’s?

RICHARD

I think the overarching subject of this book is reconstruction. The poems are lonely because I started writing them alone in a hospital bed, then finished them alone in my room. I think the overarching subjects for all of my work are identity and representation. Crush deals with the boundaries and ruptures of self and other. War of the Foxes deals with the multiplicities and dislocations of identity. I Do Know Some Things deals with the reconstructions of a self, a language, a history.

KARAN

Throughout this book, you’ve chronicled damage with clarity and force. These poems can be read as immersed in a look-at-my-pain attitude. “Music was too much to handle. It was overwhelming, but I was afraid of the silence. In the silence, I could hear my thinking: the constant narration of how damaged I was.” At the same time, there is heightened awareness of self-obsession, and also self-criticism: “Really, I’m just a little guy, so I try to make as much noise as I can. I fill everything up with my own stupid voice until I can barely breathe.” Where’s the line for you between confession and self-absorption? And when does an artist’s obsession with the self become relevant to others?

RICHARD

When you describe it, you are sharing it or evoking it. You are using yourself as the example of something larger than yourself. The more commentary or attitude you add into the mix, the more you risk sliding into something smaller and more limited. You want to vary the strategies. (You always want to vary your strategies.) I like to describe for the most part and then puncture the description with a very honest, emotionally charged, personally invested gesture. I think great literature is about the reader, not the author. The author is an example or a possibility for the reader. People used to ask me if the stories in War of the Foxes were true, which is silly because the stories are about talking animals. What they were really asking was “Can this happen to me?” and the answer to that is “Yes.”

KARAN

Your poems have had a consistent captivating voice for over two decades now. Your voice is almost always a wondrous mix of colloquial and lyrical, ironic and sincere, meditative and provocative, humorous and melancholic. Here’s a question about the capital-V “Voice” that all writers want to “find.” Is poetic voice something one “finds”? If so, how did you find/construct yours? Is the work toward having a “unique poetic voice” a worthy occupation?

RICHARD

In addition to hand writing and typing, I recorded myself. I paid close attention to my vocabulary set, to my way of telling or explaining. I listened carefully to where I would breathe and I would use punctuation and line breaks to support and represent the units of breath. If you want to learn about voice, it makes sense to listen to your voice and honor its cadences and silences. In “Time Travel,” I talk about the change in my use of language. I say “There wasn’t anyone to talk to but I practiced speaking out loud. Some words made my body hum. I didn’t like them. I used the words I could keep in the front of my mouth: quick, this, yes. The back-of-the-throat words made me queasy. Grease, glaze, sing. Phlegm, plague, Baton Rouge. Strangled and estranged. I didn’t like the throat feel, like glue or heavy cream. I didn’t like the reminder: This is your body, your stupid body. I didn’t want to be in this body, to make these sounds.”

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, and the answers are always wildly different: There’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four major axes — poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. And of course, as any good poet, I see all of these elements in your work. However, if you were to place your work in any of these categories, where would you? And do you feel it’s moved over time? Are you already thinking about where you’re headed next?

RICHARD

Again, I am various. Crush is poetry of the heart, War of the Foxes is poetry of the mind, I Do Know Some Things is poetry of the body. In grad school, I was warned that it’s easy to write the same poem, over and over, for your whole life. I was warned that it was hard to shake your obsessions. I figured if I was going to write the same poem every time, I would make sure that I would write it differently in each book. I change the form, the subject matter, the angle of approach, the direction of address, the emotional distance. I change as much as I can. Crush made great use of the second-person. War of the Foxes is anchored by third-person fables. I Do Know Some Things is in the first-person. As for what comes next, I only have notions. It’s too early to talk about it.

KARAN

You’ve won prestigious prizes since your first book, have received major fellowships, and have long been a kind of guru for people on Twitter. What would you like to say to emerging poets, by way of advice or caveats?

RICHARD

We’re in the habit of comparing our work to the best work of all time. Make sure you also read stuff you hate. When you read stuff you hate, you realize that you have something to say and a way of saying it.

KARAN

Would you offer our readers a poetry prompt, Richard, to help them begin a new poem? I’m sure many people will try any prompt(s) you offer.

RICHARD

Take the last line of the last poem you wrote and make it the first line of a new poem. Change your concept of the reader (try writing to your mom or an enemy) and change your tone. Address the same situation or theme.

KARAN

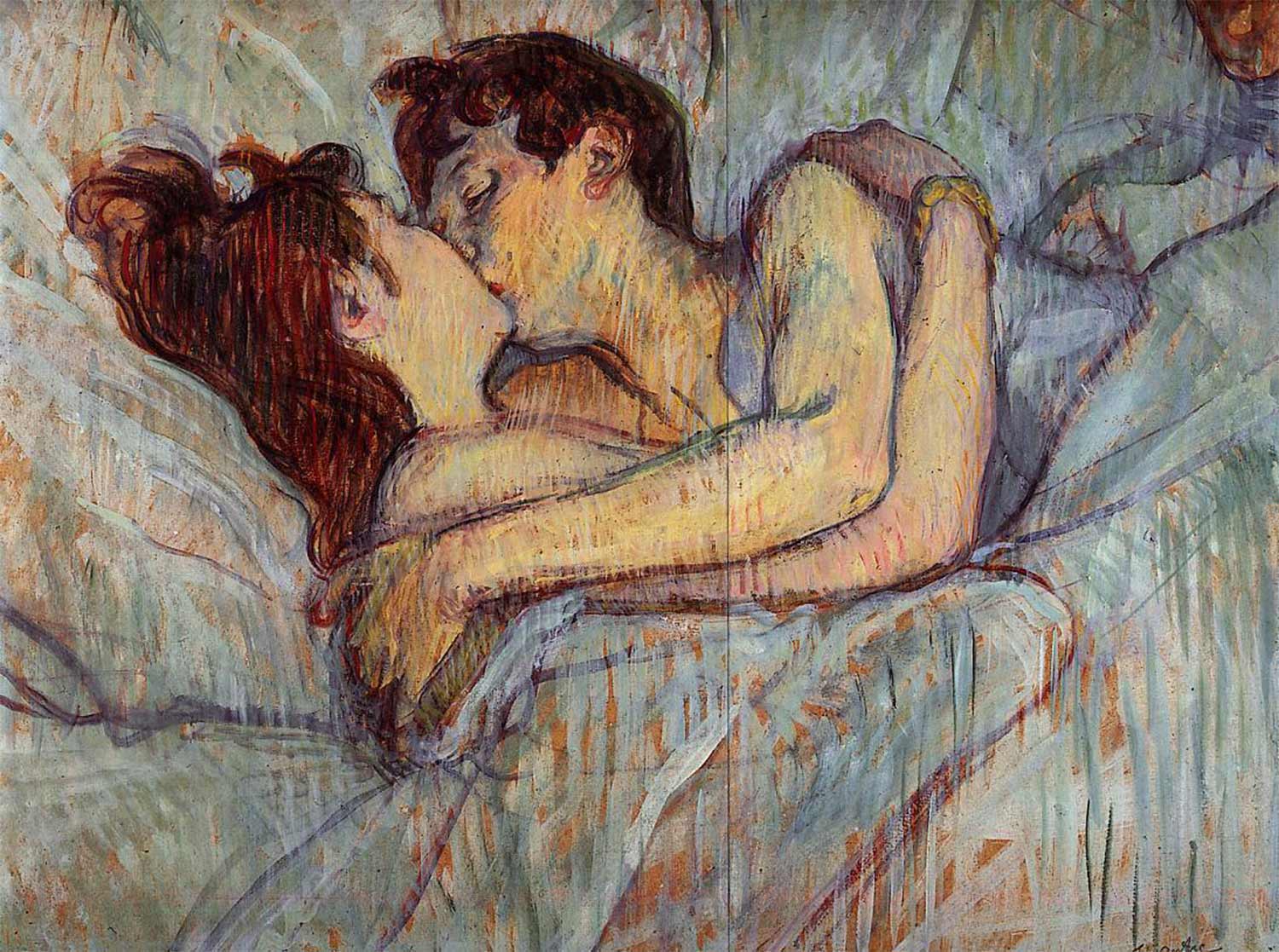

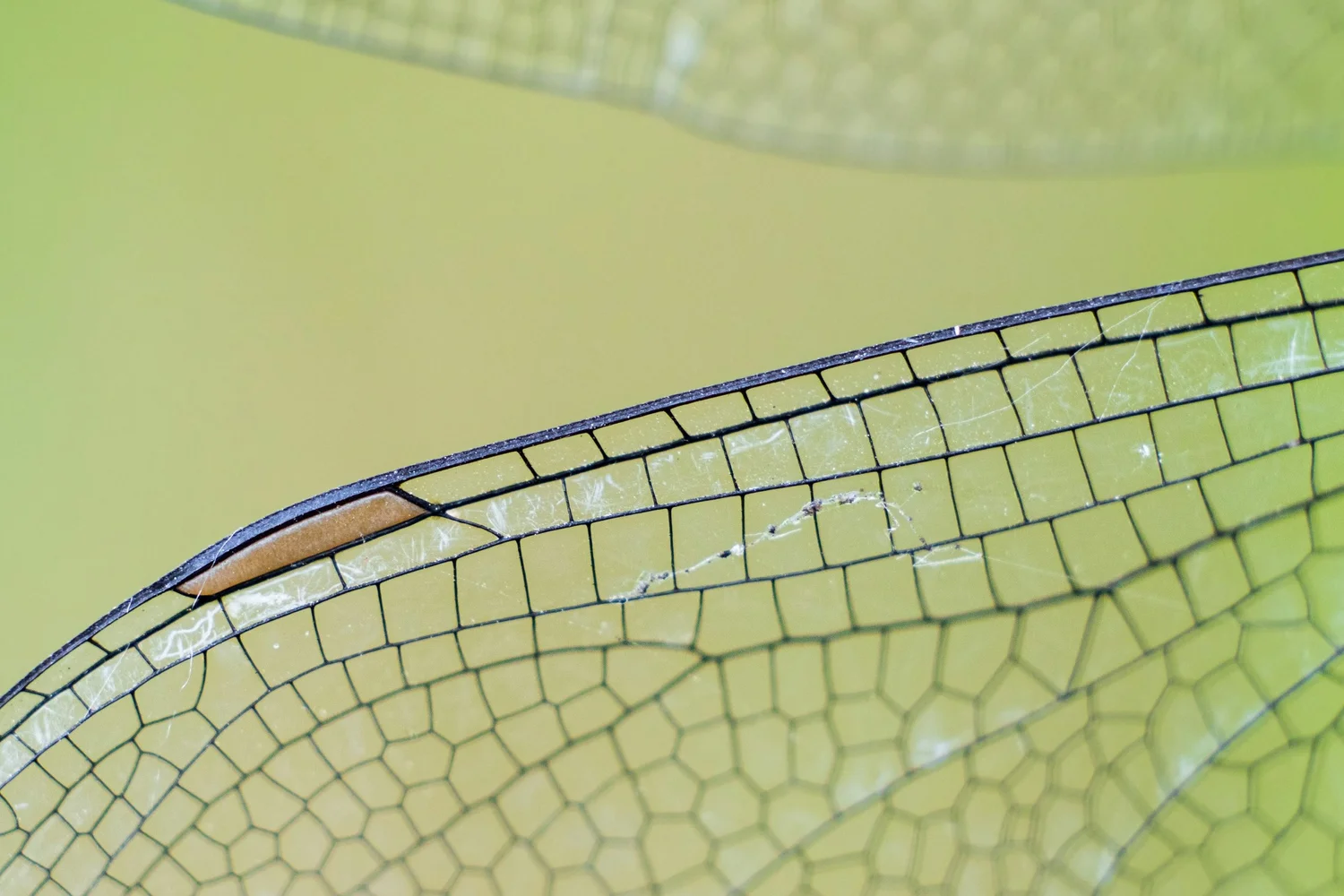

Please also recommend a piece of art (not a poem) that you keep returning to — a painting, a film, a sculpture, a recipe, anything — that haunts or sustains you.

RICHARD

I wrote a poem about three paintings I continue to return to. You can read it here. There is also a secret fourth painting that I wrote about that you can read here.

KARAN

And of course, because we believe in studying the master’s masters: which poets have had the strongest influence on you?

RICHARD

There are some questions I always refuse to answer. This is one of them. I have my excuses: “You get the page, I get the rest” or “I want to give you everything but you don’t need everything.” To be more forthcoming about it, I can say that I like talking about poems and ideas. And though I confess to many things in my poems, it doesn’t mean you get an unlimited backstage pass. My influences are private. They’re part of the secret recipe. Don’t follow my path, don’t read my personal syllabus or go through my desk. Don’t get lost in tracing my trajectory. It leads to biography and psychoanalysis. It leads away from the work. I could list some names and you could nod along knowingly but you would probably misunderstand what I was looking for, what I found. It’s as useless as charting my horoscope. “Oh, he’s a double Scorpio. That explains so much!” It makes me bristle. And boy, what an awful way to end an interview. Let me ask myself a question.

RICHARD (AS INTERVIEWER)

What’s another piece of advice you would give to an emerging poet?

RICHARD

These are the things that you need to fight to hold onto: Stay curious, stay tender (so hard to do), be humble and don't get bitter. Stay flexible and resilient. And remember that you might be the only one that can say the thing, solve the problem, or invent the tool.

RECOMMENDATIONS

POETRY PROMPT

Take the last line of the last poem you wrote and make it the first line of a new poem. Change your concept of the reader (try writing to your mom or an enemy) and change your tone. Address the same situation or theme.

MOST INFLUENTIAL POETS

My influences are private. They’re part of the secret recipe. Don’t follow my path, don’t read my personal syllabus or go through my desk. Don’t get lost in tracing my trajectory. It leads to biography and psychoanalysis. It leads away from the work. I could list some names and you could nod along knowingly but you would probably misunderstand what I was looking for, what I found. It’s as useless as charting my horoscope.

%201990%2C%20Gerhard%20Richter.jpg)