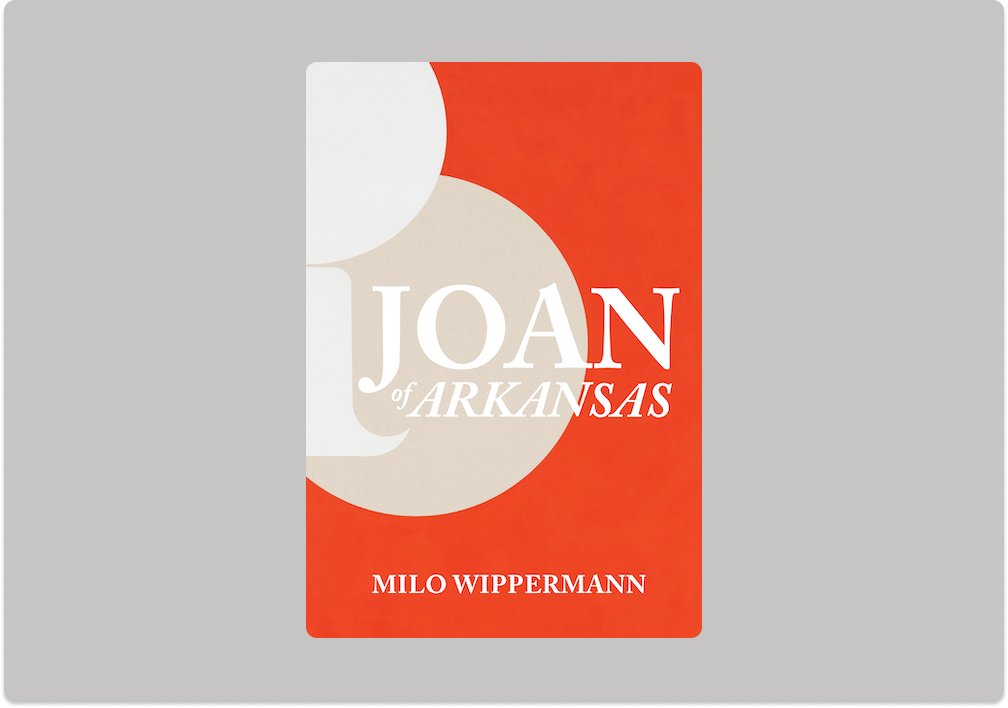

Joan of Our American Crisis

A review of the cultural resonance of Milo Wipperman's Joan of Arkansas, a hybrid collection of prose and poetry

Milo Wipperman’s Joan of Arkansas struck a chord with readers when it was published in 2023. Two years later, the hybrid book continues to intensify in its cultural resonance to a point of sharp ringing that feels pressing, almost prophetic.

The longest portion of Wipperman’s project is an experimental play reimagining Joan of Arc’s story, where Joan is a nonbinary 21st-century teenager who can hear the voices of angels and God. In response, Joan makes videos on social media advocating for sustainable climate policy for their rapidly increasing millions of followers. When Charles VII, the current Republican governor of Arkansas, announces his presidential candidacy, Joan hears God’s voice telling them that if they help Charles become president, he will agree to turn around all of his conservative policies to “stop emissions, end drilling, welcome migrants, give land back and provide reparations”. Predictably, Charles betrays Joan and his promises upon election. The following sections of the book, including found poetry taken from Joan of Arc’s 1431 trial documents, create a collage of history and emotional insight.

In light of Trump’s sweeping re-election, and his enactment of radical, aggressive executive orders during his first weeks in office, the American political landscape has shifted with the very swiftness and absurdity evoked by Joan of Arkansas. The wildfires that destroyed thousands of homes in Southern California have brought the destructive stakes of climate change into sharp focus. In an era of increased visibility yet continuing demonization of transgender and queer youth, insistent climate crisis, and a steep shift toward political authoritarianism, Wipperman’s intuitive, innovative writing weaves together resonant stories from the far past, recent past, and currently-unfolding moment. In doing so, they invite readers to stop looking away and engage with our reality, however painful. When we make this choice to engage, Wipperman shows us, we can access liberating modes of experimentation, rebellion, and empathy, becoming able to embrace profound transformation.

Paradoxically, Joan of Arkansas helps readers engage with the stakes of their current moment by framing and remixing it with the historical past. The book begins with a short poetic recounting of the history of Petit Jean State Park’s namesake. This story of Petit Jean/Adrienne Dumont’s cross-dressing, death by fever, and burial on Osage land speaks to the deep colonial roots of the crises we face. Wipperman goes on to create an urgent, anachronistic sense of time with the play section, beginning with the title page:

TIME

The future, now–

or, Election Season

–but with the Medieval logic

of the Hundred Years’ War

Through this carefully mind-bending turn of language, the medieval past, the present, and the future are woven together inextricably. Wipperman goes on to instruct that if the play is performed onstage or read aloud, the parts should be spoken: “with a lot of speed…talk as fast as you can read. No one waits for anybody to finish speaking. Imagine a fifteenth-century brain on amphetamines with full knowledge that the earth is burning”. This hyperaware jumble of the past, constant overstimulation, and anxious forward focus feel reminiscent of the way it feels to scroll through a frenzied social media or news feed. Through these theatrical descriptions, Wipperman imagines a conception of time that is just strange enough to resonate with our frenetic consciousnesses.

In another move that engages and disrupts the boundaries of readers’ minds, Joan of Arkansas’ language purposefully blurs together subject and object, God and social media, influencers, and those who are influenced. In a pivotal play scene, Joan heeds the instructions the voice of God imparted to them and has their mom buzz their hair on a live stream:

The rain beats down

on the house

MOM OF JOAN

turns on the clippers

and They hum

FOLLOWERS

ZzZZZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZzZz

MOM OF JOAN

MMMRRUUGGGGHHHHHHHHH

The placement of “They” in “They hum” troubles the boundaries between the hair clippers, the followers on social media, Joan, and God (who uses capitalized they/them pronouns throughout the play). This blurring of lines continues as Joan addresses their followers: “Oh…God/witness/viewer/clouded/flank of carnations/this God’s system floating/on the flood of Themselves”. Joan’s metaphors trace the disorienting collective energy of social media, which assembles its power from the participation of millions of people and is directed by complex patterns of viral growth. Social media can serve as a flawed news source, a window into lives across the globe, a tool that launches people from anonymity to celebrity, and a double-edged sword that makes and unmakes reputations. By evoking all of these potentials, Wipperman raises philosophical, spiritual questions about the implications of social media.

After Charles betrays Joan and God falls silent, the play ends and Wipperman turns to their most direct historical innovation with the section “The Trial of Jeanne d’Arc: Some Excerpts”. Wipperman presents gripping, thoughtful erasure poetry created from translations of the actual trial records. The cruel, repetitive condemnations of Joan of Arc in 1431 for her masculine dress and refusal to repent provide a portrait of systems of political violence that resonate across centuries. Joan’s voice comes through at brief astonishing moments, too, like when she responds to accusations about her clothing: “The dress is a small/nay/the least thing”. The power of this insistence that a person presenting how they wish should be a legal triviality hits home in this moment of political attacks on trans youth led by the US President. Though Joan initially apologizes and “repents”, they finally “relapse” into masculine dress and are ordered to be executed. In this moment of text-declared failure, Wipperman’s poetics of erasure highlights persevering ideas of rebellion and hope:

relapsed and impenitent

obstinate contumacious

she had no further hope

in the life of this world.

The word contumacious is significant here. In a legal context, it means contemptuous of the court. In a more general sense, it means proud, rebellious, or insubordinate. This quality of being contumacious in the face of persecution is part of what makes Joan of Arc such an inspiring pop culture icon today. The final line of the section, though, “she had no further hope/ in the life of this world” raises the difficult question of how to possess an intact sense of faith in the face of crushing injustices.

The book’s final prose section is a kind of response. Wipperman writes from the point of view of Joan of Arkansas’ friend and eventual lover Adrienne, incorporating Adrienne Dumont/Petit Jean’s history into an intimate psychological portrait of love and grief. As Adrienne grows closer to Joan, she realizes that she has spent years suppressing her deep anger at the state of climate destruction and inaction in American society. This cognitive overwhelm is only subsumed when Adrienne can engage in honest conversation with Joan about the difficult realities the world faces. When Joan sacrifices their life while fighting wildfires in California at the end of the book, Adrienne experiences the pain as acutely as if it were occurring to her body:

The water in my body steamed; I was a crater, a pitted void left after tectonic action; still smoking as the rest of my cells gave way–cilia, cell wall, nucleus. Mere feeling. My eyes were still open, and I looked up. I saw a white bird fly out of the trees.

I love you so much, They said.

Through Adrienne’s deep love for Joan, she can enter into a deep identification with their suffering and the land’s suffering, to the point where the boundaries between her and the earth begin to break down. The use of “They” to describe the white bird further blurs together Joan, the bird, and God. The dissolving of harsh boundaries separating humans from each other and the rest of the earth in this final line offers expansive hope among the ashes of destruction. It is through love, a deep empathetic witnessing, and the willingness to topple these boundaries, Joan of Arkansas concludes, that a new path towards faith emerges. Indeed, the playfulness and innovation of the book have been guiding our imagination of new ways to read, love, grieve, and live throughout. Within all of us, Wipperman suggests, lies the power for boundary-breaking resistance, love, and faith in response to crisis. It is up to us now to continue channeling and choosing it.

%20(1).png)

%201.png)

.png)