The Spiritual Mystery of Poems

In conversation with

On writing beyond words, humor as survival, and the strange logic of mystery

.png)

KARAN

Thank you for all you’ve done for the arts, David. You open the introduction for the book with a deeply funny, self-effacing line—“Just what the world needs now—a bunch of poems from an actor”—but it quickly transfigures into something far more sincere, even sacred. You call poetry “a doomed mission” which I resonate with. What does poetry allow you to say or confront that prose or performance or even a song does not?

DAVID

I don't know. It's like an intuitive sense of: this is a poem, this is a story, this is a novel, this is a screenplay, this is a song. It's an intuitive sense of when you're treading on territory that is unknown or unknowable—when I'm having thoughts that I think are beyond words. The words start to align themselves on the page in a way that is shadowing something that can't be said directly. I suppose that can work in a song too, but songs are kind of propelling you forward all the time, rhythmically, whereas with a poem, you can kind of sit down in it, reread it. I don't know, except to say that something feels like a poem when there's a mystery there. A spiritual mystery. Something feels like a story when there's a plot mystery. Something feels like a song when there's a melodic mystery. I think that's the best I can do.

KARAN

Would you walk us through your process of writing a poem (perhaps through “Do Over,” the opening poem of the book and one of my favorites)? What does your process look like structurally, emotionally, spatially? Where do your poems come from? Do you usually begin with a line, a thought, a feeling, an image, or something else entirely? Do you have a writing routine?

DAVID

I don't have a poetry writing routine. If I'm writing a novel, I'm pretty much in the seat from 5 a.m. to noon. Poems are not disciplined like that. You know, they don't take that kind of months-long discipline. They're short bursts—for me, anyway—I've never written an epic poem. Maybe I should try that. How do they come to be something like "Do Over?" That's an older poem, and it would have happened over a span of some time. And those stanzas kind of stand in for a passage of time or a different consciousness. Often, if I have stanzas, I'm attacking the same problem in a different way. I'm thinking of "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird" by Stevens. So my stanzas would be like that to me. That's how they feel. It's like, okay, well, I've exhausted this way of looking at something, didn't get all the way there, or got somewhere. And now I'm going to look at it from this other angle. I'm reminded of...what is it? Is it Borges and the elephant? You know, different people touching different parts of the elephant and not knowing it's an elephant, just thinking it's some other kind of animal. That's kind of how I think of a poem. A longer poem like "Do Over" is like that. It's touching all these different parts of the elephant, and hopefully you get the elephant at the end, or some kind of mythical animal. I can begin a poem with a line, sometimes, a phrase, a thought, or an image—all those things can happen. There's no rhyme or reason to it, really.

KARAN

In a lot of these poems, especially thinking of “Nobodaddy Home,” there’s a sense of inheritance and annihilation braided together: the father not as ghost or memory, but as aesthetic predicament. The whole poem feels like it’s circling a comic and cosmic wound. Let’s talk about fatherhood—both literal and literary. You take Blake’s absent father-creator and bring him into the contemporary psychic kitchen, sugar-covered phone calls and all. “It is not the hole that hurts, / but what you put in it.” How do you approach writing about the father as subject (your own, and also fatherhood as structure)?

DAVID

Whoa. I mean, that's a great question. It kind of answers itself, though, doesn't it? I mean, I wish I had said that. I could just say that without the question mark. Yeah, fathers and fatherhood. I guess they loom large in these poems, and literary fatherhood. You know, coming out of Harold Bloom at Yale, Anxiety of Influence and all that, the Oedipal struggle of one poet against another, precursor poet, the sense of belatedness—which is really a sense of sonhood, isn't it? Not fatherhood. Yeah, thanks for picking up on the Blake. I don't think anybody's done that yet. I always liked that phrase: "Nobodaddy."

KARAN

Your poems here are populated with fugitives and phantoms—men on the lam from their own desires, their pasts, their fathers, their definitions. In “Heads or Tails,” you write: “We are subjected to the shorthand of the master— / thus this one reclines ambiguously.” There’s a sense throughout these poems that inherited language and gesture—especially from gendered roles—can become traps. And the poem stages a kind of exorcism through surreal memory: a radiating house, a father not crying, a lover coin-tricking history. Oof, there’s so much here I’m struggling to find a thread, sorry. Here we go: are you thinking about masculinity, or the fractured version of it we now refer to as toxic masculinity?

DAVID

I don't like that term: toxic masculinity. I don't like the term "toxic." Well, "toxic" is not a term, but "toxic" is overused. Everything "toxic" this, "toxic" that—complicated masculinity, it's not toxic. It can be complicated, can be dangerous, can be hurtful, but I don't think it's ever toxic, because we need it, just like we need femininity. But that's just all philosophical, theoretical. In the poems themselves, no, I don't think I'm interrogating masculinity, per se. I may be interrogating my own sense of masculinity, but I'm not saying that's part of any culture or anything I learned, though it probably is—no doubt it is—just because it wasn't foremost in my mind doesn't mean it's not in the poems, but no, it wasn't foremost in my mind.

KARAN

Throughout the book, multiple times I thought of what Barthes said in A Lover’s Discourse—that the one who waits in love becomes a “figure of the melancholic philosopher.” Your poems seem to play with that figure while refusing to be sentimental. Humor seems to be your way of getting out of it. I laugh as I’m experiencing pangs of sadness. Your humor seems to hint at an undercurrent of sorrow. Is humor a coping mechanism in your writing? Or, more generally, do you see humor having an important role in poetry at large?

DAVID

Humor is just an important element of who I am. It's going to come out in any expression that I do. To me, it's really the touchstone of humanity. The absurdity of existence, and a great, great source of anger and sadness can be dealt with only through humor, I think. I'm not talking about stand up, but I'm talking about a remove where you can see the players at play, not take them as seriously as they might take themselves, or take yourself as seriously as you might take yourself. I hope to always be able to laugh at myself and those around me. Does it have a place in poetry? Well, it's pretty rare that poems are funny, isn't it? What are some funny poems? I don't know offhand, but I like to write them. I think that it's worthwhile.

KARAN

You often fold time over itself—“The page of your mind was bare / and the world was changed” (from “A Dream”) or “some beautiful-ass nonsense, / or the starting up again / of what has never been” (from “Future Perfect”). There’s something Beckett-like in how these lines both unravel and renew time. What is your relationship to time as a writer? Does poetry offer you a way to give shape to something that exists outside the reach of memory or history?

DAVID

Yeah, I think the logic in poems is more dreamlike. But obviously, much of my experience as a working adult has been on sets, acting, telling stories that way, and it's going to inform my vocabulary. It's going to inform the way I look at things, the way I look at scenes. I think of Frost when I think of dramatic poems. I don't think I've written one quite like that. Maybe "Carbon Canyon" is a scene. Maybe some of these poems are scenes. They're symbolic scenes. But a poem unfolds itself not narratively, that way—there's a different temporal narrative going on in the poetry scape. That's the beauty of it, I think, and why it's so surprising sometimes when a dramatic poem works. It's like those songs—mostly country songs—that are like "story" songs. That's "The Night the Light Went Out in Georgia," "Delta Dawn," "Brandy"—songs like this, sometimes they work beautifully. So, you know, sometimes they can work in poems that way too, a little movie poem.

KARAN

In the introduction, you quote T.S. Eliot: “Poetry is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.” This ethos shows up throughout the book, especially in the roleplay and shapeshifting—hearts as detectives, fathers as ghosts, the self as almost always split. And in your own words, poetry becomes a trance, a possession, a vanishing act. Do you think writing reveals the self, or dissolves it?

DAVID

Yes, both!

KARAN

I’ve been thinking of: “All poems are about death. All poems are about love and death.” I love that poetry allows us to explore these vast subjects that so often evade language. Forgive me for being rash, but are you preoccupied with death? In the sense Garcia-Marquez was with solitude, or Beckett with futility?

DAVID

I don't think that I walk around preoccupied by death. But if you were to look at these poems closely, maybe there's a lot of death in them. Not my own, though—my father, my mother, the perspective of death of a child (which is what Bucky F*cking Dent is about). Yeah, I mean, I don't think of myself as a person that is necessarily afraid of death or thinking about death a lot. It's more that I think about time passing, and of course, the last bit of time that passes is your death. So there's a conjunction there maybe to be made. But, you know, if you were to talk to me, I don't think I'd bring up death in a conversation, ever—my own or yours.

KARAN

Would you offer our readers a poetry prompt (something strange, simple, or rigorous–whatever your wish, really) to help them begin a new poem?

DAVID

Write the shadow of what you believe.

KARAN

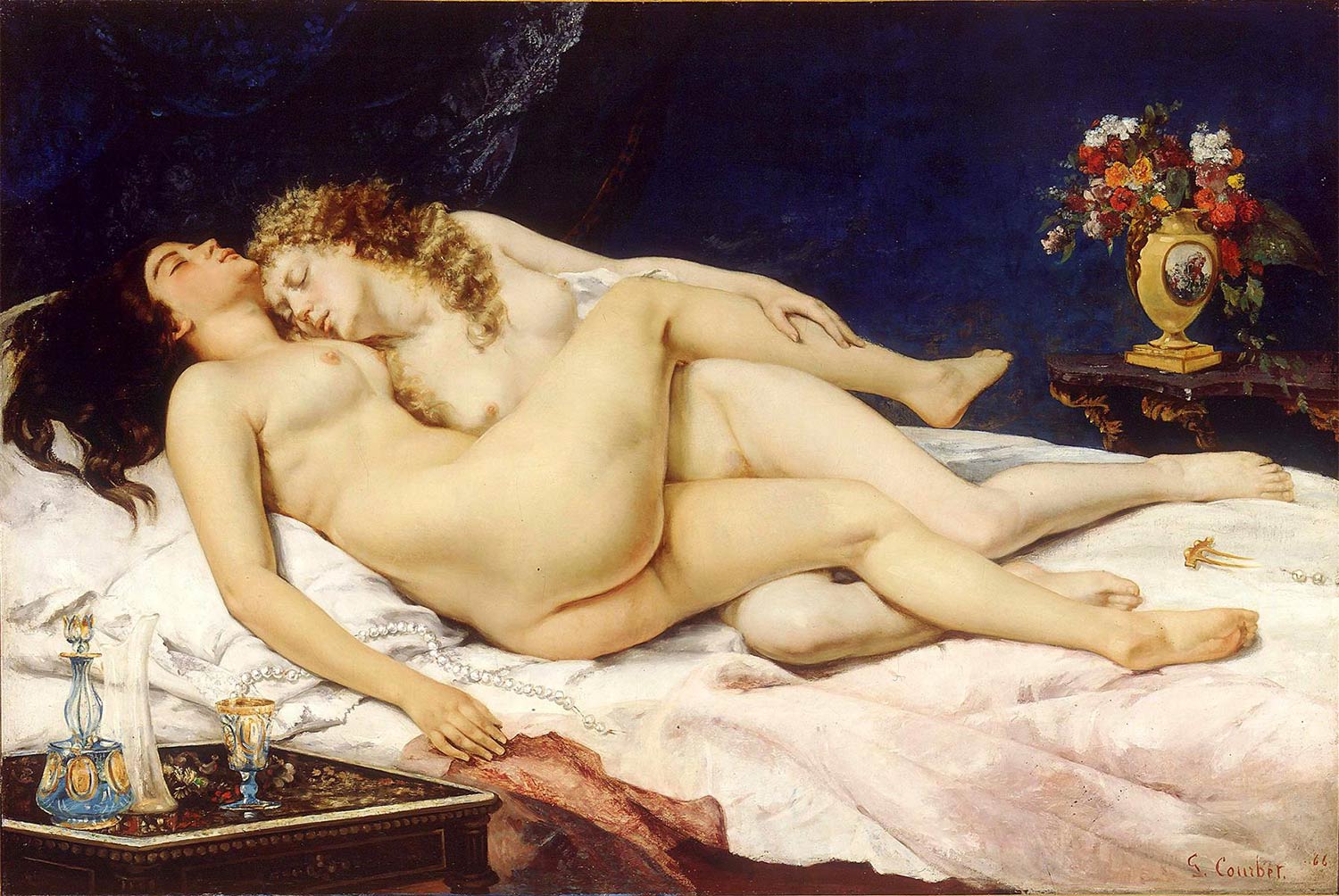

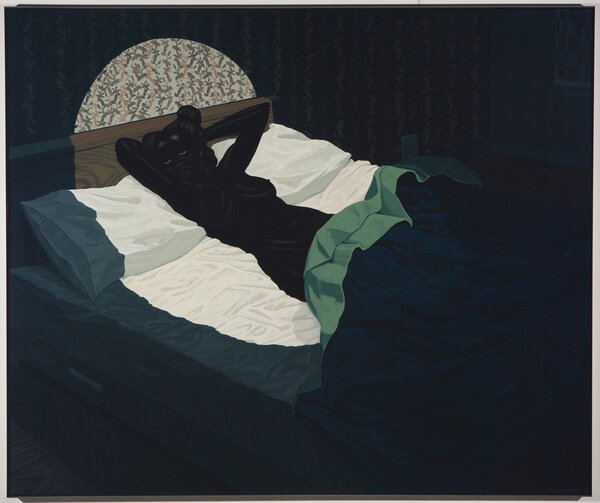

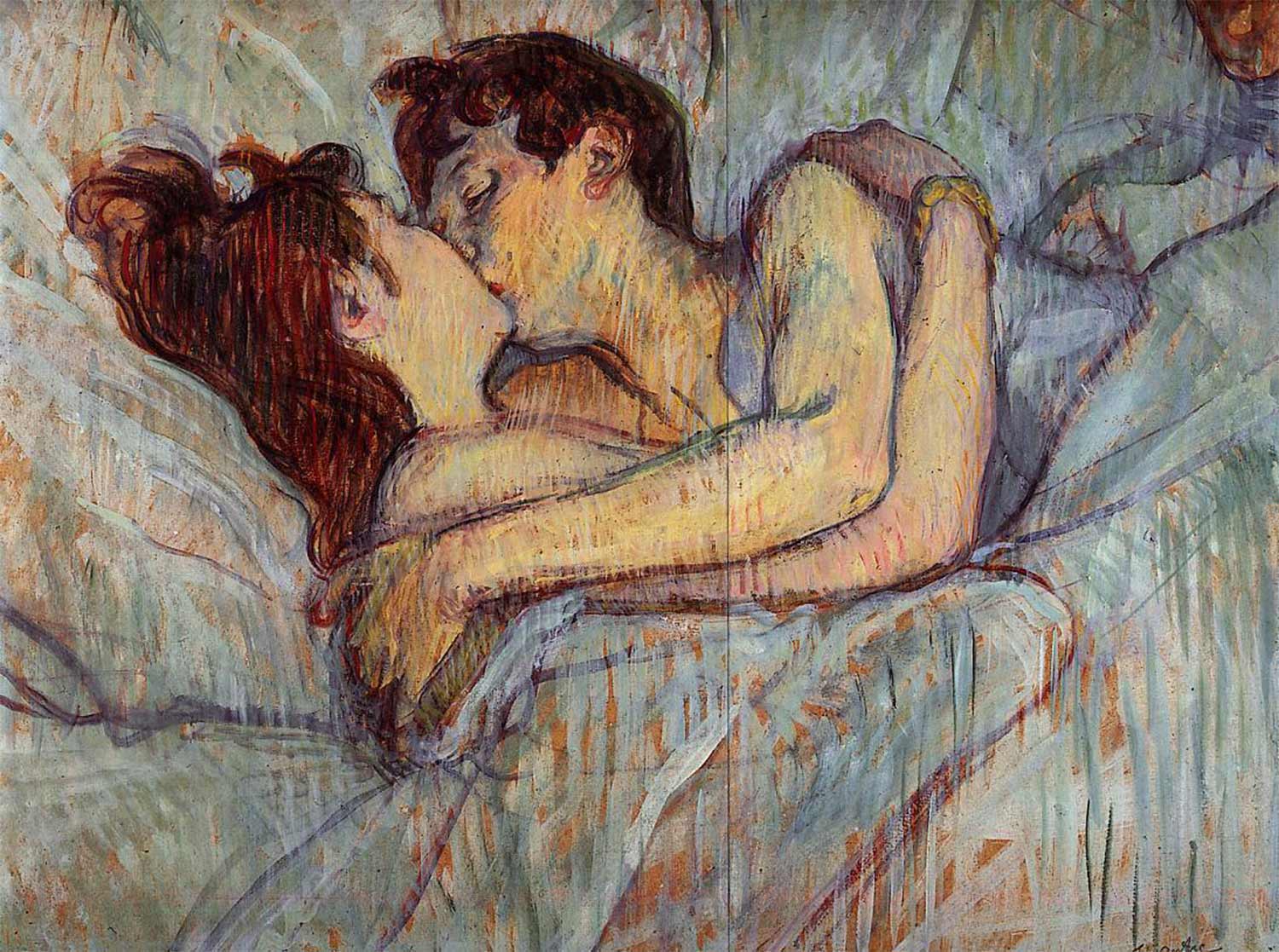

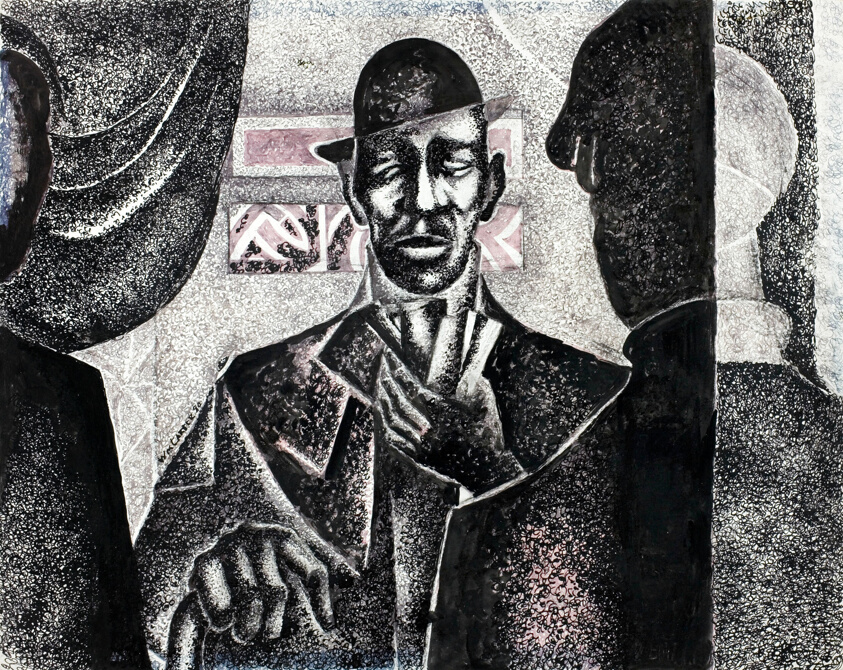

We also ask all our poets for a recommendation of something outside of poems or poetry. Would you also recommend a piece of art — a film, a painting, a song that’s sustained you lately or that you feel everyone ought to sit with.

DAVID

Oh, wow, gee. I don't know. I'm blanking on this. So sorry. There's so much that can feed you.

KARAN

And finally, David, since we believe in studying masters’ masters, who are the poets that have shaped your sense of what’s possible in language, your strongest influences? (Would also love to hear what you admire most about Ashbery, O’Hara, Stevens and others who I failed to notice in your work.)

DAVID

John Berryman as I said in the intro, Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, maybe Frank O'Hara, Shakespeare, John Donne—I love the metaphysical poets. I love the violence of the juxtaposition of images. It's very surreal, especially considering when he [Donne] wrote. [John] Berryman I love for his humor, his colloquialism. I love the romance of Yeats, the physical desire, the sensual world—like in "Crazy Jane." [I admire] Auden's facility with language and rhyme. In Stevens I love the philosophy as spirituality—really the death of God in Stevens—an aesthetic replacing a sense of an all-powerful God, an all-powerful aesthetic, sometimes bloodless, but clinically precise. And then Ashbery—just the constant evasiveness, the unwillingness to say anything plain, always subverting—the ability to create sentences that seem to be declarative of some kind of knowledge or fact, but when you go back to them and try to unpack them, they're really a fake-out or a mist. I try to, I try to write lines like that sometimes myself.