Poetry of the Mages: William Butler Yeats

Samantha Weisberg on mysticism, the spell-like qualities poetry in general, with focus on the occult life of William Butler Yeats

.png)

Poetry is magic. Poems are incantations. Speaking the words aloud allows for a shift in the ether, manipulating will, and provoking cause and effect. Much like the Kabballah, when you speak the letters into existence, they create worlds. William Butler Yeats believed in the arcane power of conceiving magic through spoken words. Many people know of him as one of the most famous poets of the 19th century; however, he was also a magician of duality, a conjurer of symbols, and a member of multiple mystical orders.

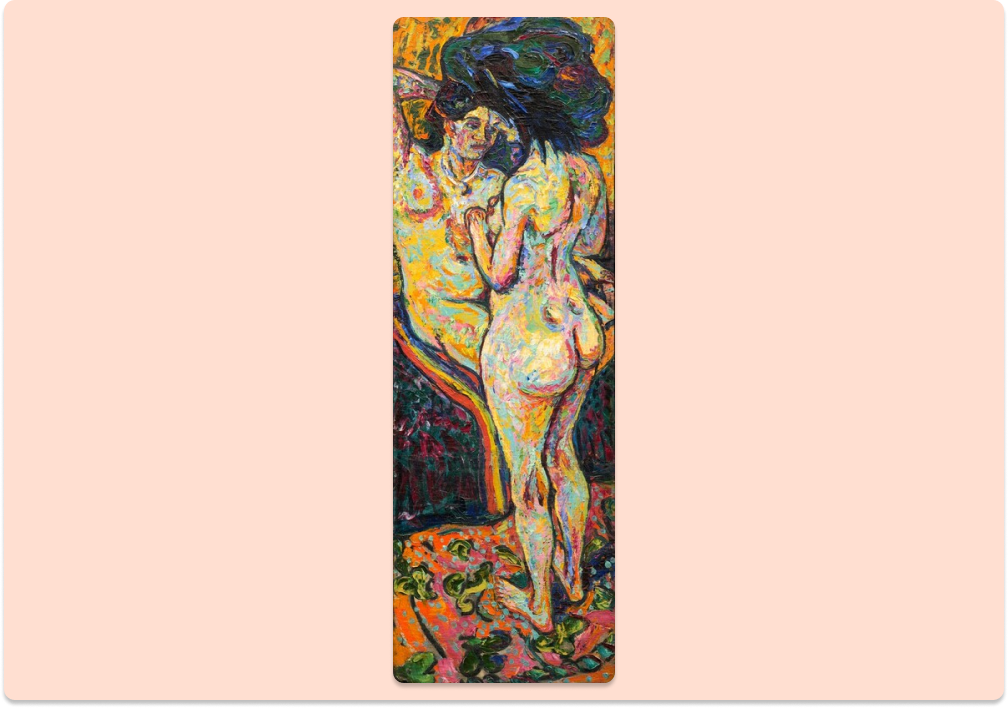

Many people briefly learn about W.B. Yeats in high school or an Intro to Creative Writing class. I remember reading Leda and the Swan. My instructor explained that it was based on the Greek myth. We learned the story, and a little bit about the politics at that time, and that was the end of it. It was decades later that I realized the poem was a powerful message of ancient matriarchal cultures being forced out by patriarchal religions. A common theme in Yeats is the rise of Abrahamic and Christian belief systems and the death of nature-based pantheistic feminine/masculine-centric worship. Through his work, Yeats showed how new belief systems are the same as the old ones, just recycled.

Not many people are aware of Yeats’ occult life. As a child raised in County Sligo, Ireland, his mother raised the children on stories of Irish folklore. Yeats and his sisters would converse on “prophetic dreams, banshee cries, visions, and visitations” (Maddox). During his time studying at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, he helped found the Dublin Hermitic Society. Later, upon his move to London, Yeats was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn during the summer of 1887 (Raine). His name in the order was D.E.D.I or Demon est Deus Invrsus, which is Latin for “A Demon is a Reversed God”. This name represents the balancing of Spirit and Matter. God is symbolized as spirit and the Demon as matter. “Whether Demon is translated as Daimon (Yeats’s word for the individual’s guiding spirit or alter ego) or more conventionally as devil, the name appropriately conveyed his lifelong commitment to the reconciliation of opposites” (Maddox). Yeats believed there is duality in everything. Without light, there is no dark. Without feminine, there is no masculine. The magician’s purpose is to use will and the manipulation of the elements to create positive results. He resigned from the Order in 1905. During his time as a member, he mastered the foundations of mysticism and out of this knowledge, wrote some of his most profound essays and poems. Using his Irish heritage as inspiration, Yeats incorporated the stories of Celtic myth and folklore into his writings. He intended to re-introduce a Celtic mystical revival into contemporary literature and poetry while blending Ancient Egyptian and Greek knowledge (Hermeticism).

Yeats would use his knowledge of Hermeticism, Irish mythology, and the Tarot to write his folkloric stories of Red Hanrahan. In this work, there are associations between a magical pack of cards and the four sacred objects in Irish Mythology. The main character, Hanrahan, has similar attributes to the Fool card (Card 0 in the pack). “He stumbled, tumbled, fumbled to and fro” (Yeats). Hanrahan stumbles through the first stage of the journey, unaware of who he is. In fact, in the poem, Hanrahan has forgotten his identity and must travel to another world where he is considered a prince. To reach this destination, he must meet the archetypes of the 21 cards. In one part of the poem, he is led by an old man (The Hermit) into the magical world. It is there where he notices The High Priestess sitting on her throne. Four crones sit at the priestess’s feet, each holding a symbolic object: a stone, a cauldron, a long spear, and a sword (Raine). These objects correlate to the four elements used in magic and ritual, as well as the minor tarot suits: Earth (Pentacles), Water (Cups), Fire (Wands), and Air (Swords).

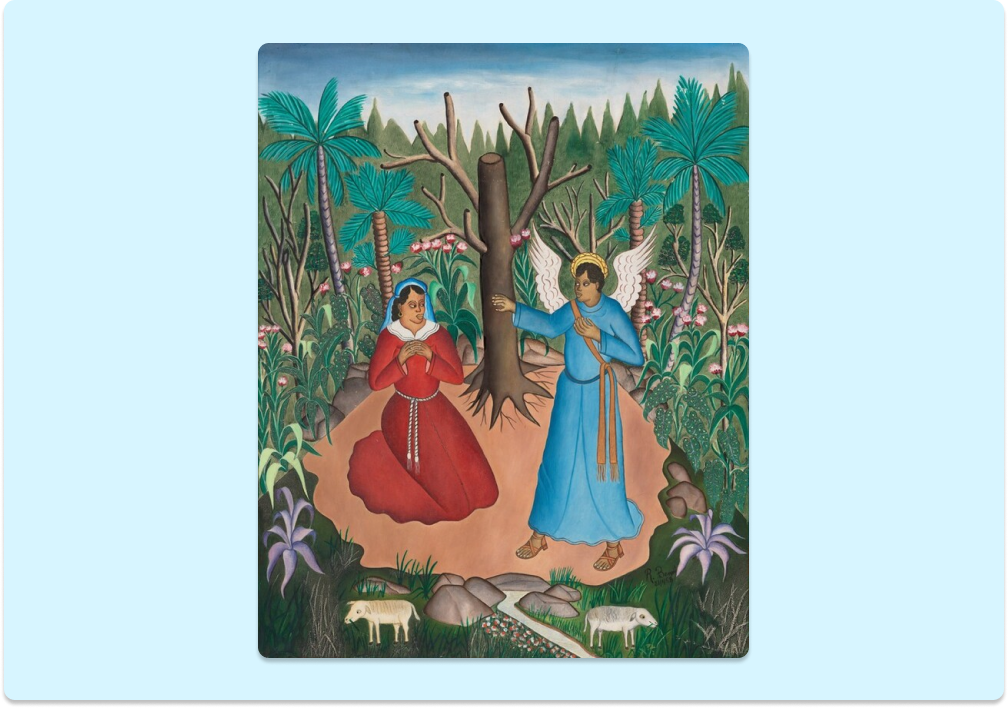

Besides the Fool card, Yeats also used The Star card in his play, The Resurrection. The play centers around three men, a Greek, a Hebrew, and a Syrian, witnessing the resurrection of Christ. Each man symbolizes a different belief system, yet all can be traced back to ancient mysticism. The Greek knows the occult mysteries from Egyptian and Dionysian rites and rituals. The Hebrew knows of the Tree of Life and the secrets of the Kabbalah. The Syrian, who shows up last, brings the news of Christ’s resurrection, introducing the birth and death of Christianity. The play opens up with a hymn to Dionysus. In Greek mythology, Dionysius was ripped apart by Hera, but then was resurrected by Zeus. With Athena’s help, by preserving Dionysus’ heart, he was reborn. As a believer in ascended masters, Yeats was proving that in every belief system, since the beginning of time, the resurrection of gods is a common thread. There is no one true resurrection, as the devout Christians and Catholics believe in.

As for Yeats’s use of The Star card, The lines, “…that fierce virgin and her Star” represent religious empires coming into existence, and then repeatedly being destroyed by something more modern. In tarot, The Star card provides the querent with the “calm after a storm”. The star shows what occurs behind the veil. The pool of water at the sky-clad maiden’s feet symbolizes the unconscious. Rachel Pollack, author of Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Tarot Journey to Self-awareness, believes this is the same pool of water behind the High Priestess (Pollack). The querent now has access to the knowledge that was once hidden. Out of one vessel, the maiden pours water onto land. Out of another, she pours a stream into the pool of water. She has one foot in the water, as the rest of her body kneels on the earth (symbolizing the balance between the conscious and the unconscious). The tree in the background shows a perched ibis, the symbol of Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom and magic. The Star indicates a link between the spirit and the outer world.

In the deck, The Star comes right after The Tower. The Tower symbolizes the destruction of a false temple or building (think of the Tower of Babel). The Star provides a glimmer of hope to the people who have lost everything. They now have to opportunity to be reborn into their truth and break away from a false ideology.

Another poem, where The Star appears is in “Parnell’s Funeral”, shows the imagery of a woman pointing an arrow at a star:

A beautiful seated boy; a sacred bow;

A woman, and an arrow on a string;

A pierced boy, image of a star laid low.

That woman, the Great Mother imaging,

Cut out his heart.

In his autobiography, Yeats explains how he invoked the spirit of the moon which aided in his inspiration for “Parnell’s Funeral”. He explains, “after night, just before I went to bed, and after many nights—eight or nine perhaps—I saw between sleeping and waking, as in a cinematograph, a galloping centaur, and a moment later, a woman of incredible beauty, standing upon a pedestal and shooting an arrow into the sky” (Raine). Similar to “The Resurrection”, there continues to be a common theme: Sacrifice in mythology or destruction and creation. Charles Parnell’s death caused a political uprise in Ireland. After death, there is a lull where contemplation occurs. Faith must be restored, symbolized by The Star card.

Another tarot card used frequently in Yeats’ work is The Hanged Man. The sacrificial imagery of The Hanged Man card can be found in his poem, “Vacillation”. In Part II of the poem, it reads:

A tree there is that from its topmost bough

Is half all glittering flame and half all green

Abounding foliage moistened with the dew;

And half is half and yet is all the scene;

And half and half consume what they renew,

And he that Attis’ image hangs between

That staring fury and the blind lush leaf

May know not what he knows, but knows not grief

This stanza is rich with Jewish, Hermitic, and Asatru mysticism. From a Kabbalistic perspective, we have the Tree of Life. The Tree of Life is symbolic of the four worlds: Atzilut (the world of deity), Briah (Creation), Yetzirah (Formation), and Assiah (Action) (Raine). Within those four worlds are 10 sephirot symbolizing moving from the earthly plane, Malkhuth, and rising to the highest plane of consciousness called Keter, or Crown. The right side of the tree is masculine and the left, feminine. The lines in Vacillation, “half all glittering flame and half all green” show that duality. Water (or dew) is the feminine or the unconscious and the abounding foliage symbolizes sustenance, fertility, and growth. Fire is a masculine symbol. “Half and half consume what they renew” represents the never-ending cycle and goal of the constant search for our other half. How can we marry the masculine and the feminine? This is also synonymous with the hermitic belief system. A magician’s goal is to master control over matter and spirit: As above, so below.

Not only does the imagery in Vacillation show the connection to the Tree of Life in a Kabalistic sense, but it also correlates with the Norse tree of cosmology, Yggdrasil. The Norse tree of cosmology stores the 9 worlds of Norse Mythology. This is the tree that Odin, the All-Father, hanged from for 9 nights to gain all the knowledge in the universe. The Hanged Man card in the tarot pack is in a similar situation as Odin. In the stanza above, Attis, a Phrygian vegetation deity, is mentioned as hanging from the gallows, or tree of life. In mythology, Attis self-mutilated, sacrificed himself, and was resurrected. The Hanged Man sacrifices themselves and acts as a scapegoat, in order to receive divine guidance. There is an abundance of the cyclical concepts of life, death, and rebirth through sacrifice in Yeats’ work. The sacrificial deity archetype is constantly repeated throughout history.

The tarot wasn’t the only inspiration for some of these works. A lot of ideas came to Yeats through the spiritual practice of automatic writing, an exercise that rose with the spiritualist movement. This activity allows messages to manifest through a channeling process. Automatic writing connects a person to a larger source such as the spirit world or the subconscious. In a deep, meditative, or trance-like state, the hand is used as a vessel to receive messages from spirits, angels, the subconscious, or ancestors. On the night of Yeats’s honeymoon, with his new bride Georgie Hyde-Lees, she suggested they try to channel a spirit and produce automatic writing. That night, as she channeled a spirit, she ended up writing around 90 pages of messages (In Our Time). Yeats later wrote, “What came in disjointed sentences, in almost illegible writing, was so exciting, sometimes so profound, that I persuaded her [Georgie] to give an hour or two day after day to the unknown writer” (Ludolph). When Yeats asked the spirits why they were communicating, the message they received was, “We have come to bring you metaphors for poetry” (In Our Time). Yeats and Georgie spent hours together gleaning pages from the spirits. 450 sessions in the first three years produced 4,000 pages — all handwritten by Georgie (Ludolph). She would often talk in her sleep and Yeats would write down every word. These words turned into his book, A Vision. Unfortunately, Georgie was never credited. Yeats did eventually dedicate the book to her; however, at the time, there was no acknowledgment that she had helped in any way.

Poetry and spells are synonymous. Poets are sorceresses and magicians. I wish more schools would introduce the fantastic mystical lives of some of our most cherished and notable poets and writers. If I was able to see the spiritual awakening and incantations within some of Yeats’ work as a teenager, I believe it would have opened up doors for me earlier on in my spiritual journey. Leda and the Swan would have been more than just a recount of a violent Greek Myth, but an unapologetic manifesto on the cycles of death and rebirth.

References

English Verse. 2003. Accessed March 21, 2025. <https://englishverse.com/poems/vacillation>.

Ludolph, Emily. W. B. Yeats’ Live-in ‘Spirit Medium’ December 5, 2018. JSTOR Daily.

Maddox, Brenda. Yeats’s Ghost: The Secret Life of W.B. Yeats. Harper Collins. 1999.

Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Tarot Journey to Self-awareness. Weiser. 1980.2019.

Raine, Kathleen. Yeats, the Tarot and the Golden Dawn by Kathleen Raine. The Sewanee Review, Winter, 1969, Vol 77. No 1 (Winter 1969). Pp 112-148.

Yeats and Mysticism. In Our Time. Podcast. BBC. <https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/ p00548b3>.

Further Reading

Yeats, W.B. The Stories of Red Hanrahan. September 1, 2002. Accessed April 1, 2025. < https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5793/5793-h/5793-h.htm>

Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Tarot Journey to Self-awareness. Weiser. 1980.2019.

Maddox, Brenda. Yeats’s Ghost: The Secret Life of W.B. Yeats. Harper Collins. 1999.

%201.png)

.png)