Where is the Love?

Exploring love’s changing role in modern poetry, with grounding references spanning from Rumi to Leonard Cohen

“I said I loved you and I wanted genocide to stop.” – June Jordan

I.

Last month, while reading Danusha Lameris’ gorgeous and steamy book, Bonfire Opera, I was struck by the realization that it’s one of the very few collections I’ve read in 2024 where the poems were consumed by themes of love and sex, which got me wondering: where did all the love poems go? I know somewhere out there is an editor groaning at the mere mention of the word love, (I am reminded of a poetry workshop recently where a participant claimed that the word heart is cliché in any poetic context) but at many points in history, arguably for most of its lifespan, poetry was the domain of (capital L) Love. Did we get it all out of our system? Is it so overwrought that we have run out of fresh ways to write about love as we have about the moon? Or is this a symptom of a society grappling with heartbreak on a grand scale, unable to let love in? On the surface it may seem that the heart has truly become nothing but a fist.

The oldest known love poem is said to date all the way back to early Mesopotamia, known today as the The Love Song for Shu-Sin (c. 2000 BCE). Archaeologists found this poem by happenstance while searching for evidence of the Old Testament, discovering cuneiform tablets which scholars believe many of the biblical stories reference. This search in itself becomes a symbol of what love poems—and perhaps the idea of romantic love as a whole—strives for: transcendence of the physical in search for the divine. In essence, the search for love, is a search for completion, is a search for God. Perhaps it is no coincidence, then, that as more and more people exit the church in droves, leaving a void of God-love, our focus happens to shift away from romantic love as well. But this departure from organized religion also means losing an aspect of community, which is a loss of a form of non-romantic love as well. All this is to say, the world has recently seen many voids open up in the love department, which may imply we need love poems more than ever.

On the heels of reading through some amazing entries in our inaugural Leonard Cohen Prize, it is perhaps no accident that the elusive quality of Cohen’s work lies in this intersection of love, sex, and faith. His timeless mastery lives in his mysterious blending of love and the divine in a way that is hard to replicate. Beyond the physical and emotional experiences inherent in love and sex, his work has a spiritual component that has always been reaching for the light. In Cohen’s songs, love and sex become vehicles for the transcendent intimacy of the spiritual dimension, flying with his lover higher than he ever could alone.

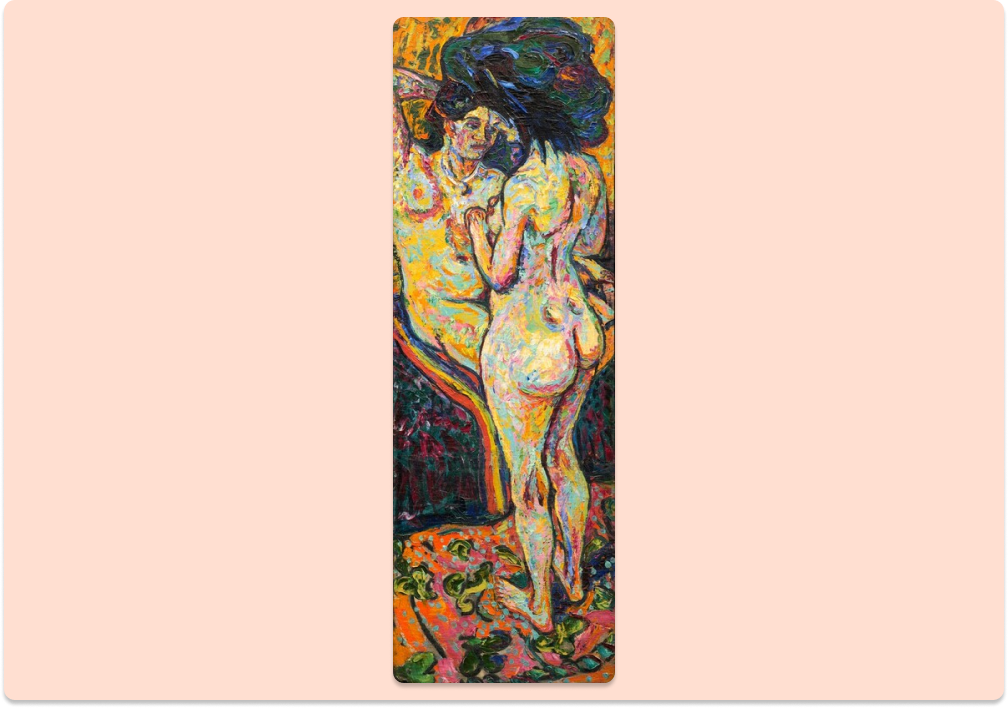

Sex often works in tandem with love, but it is not synonymous with it. Sex remains our constant obsession; there is no shortage of it in poetry, literature, or music. Many journals and presses today are poised to publish the edgy and vulnerable, the raw and naked. Our feature on Chen Chen in 2024 is a perfect example of the delightfully voyeuristic quality that characterizes modern sex poems, perhaps in their own way counterbalancing centuries of puritanical repression, the likes of which spurred the phrase, “there is no sex in the USSR.”

This is relevant in the context of modern poetry as an inverse relationship begins to form where love poems appear to have fallen out of fashion, today commonly considered corny, cloying, overly sentimental, the stuff of 90’s pop song lyrics, “Hallmark movies,” and “chick lit.” Confessional poems are having a moment, but it might be argued that heart break and sex poems are not love poems at all but are actually a kind of antithesis to them—anti-love poems. That, once modern love poems are fully undressed, they might be revealed as political poems. And certainly, this concept is not new—the personal has always been political. All the same, today’s poetry explores the way the body is a political space, a battleground, a place of violence and war. Poetry is powerful and fluid, and in times of war, it does what it has to, even if it means becoming a weapon, a tool for change.

Today’s poems sometimes read like a love poem to the self. They are celebrations of individuality as well as demands for agency and healing for those parts of ourselves we have been told are unlovable. Instead of romantic love, the focus is often on themes like body positivity, queerness, and gender fluidity peppered with specific and graphic details, often endeavoring to shock to potentiate acceptance. By increasing visibility of sex and gender’s darker sides, reading audiences are invited into artists’ bedrooms while the act of sex is simultaneously being coaxed to exit bedrooms— and by extension, closets. In this way, visibility becomes a tool for reclaiming power, subverting traditional power dynamics by inverting the critical gaze, by staring back and refusing to stay hidden any longer.

Art reflects life. Perhaps the lack of love poems simply reveals our artistic priorities. The artist carves their subject out of the marble of their own subconscious—their own wants, needs, values; the object of beauty that keeps them up at night. Undoubtedly, the number of armed global conflict trend upward to new and devastating heights, economies are on the brink of collapse, ice caps are melting and Los Angeles is on fire, we just (sort of) survived a pandemic, and fascist dictatorships threaten to overtake the world. There’s a lot vying for our attention. So, it comes as no surprise that romantic love has had to take a backseat to more pressing social issues in contemporary poetry. It is important to recognize and appreciate where we are positioned in history because the implication that love isn’t the universal emotion we once thought it was would otherwise be an easy oversimplification to make.

II.

Love sits at the peak of complexity in the range of human emotions. When we are creatures falling in love with our own pain, happiness becomes a niche market, relegated to genre. It might seem that the public isn’t in the mood for romance, but literary statistics say otherwise, with romance being the number one best-selling genre, accounting for one third of all global book sales. Even today, hundreds of years after his death, the world’s best-selling poet is still Rumi, who wrote primarily about romantic love.

But, in recent years poetry has been working overtime, busy tackling all the issues that require it to step up and don armor, to accept its role in social activism. We simply can’t afford the luxury of basking in the lighter parts of love. Or as Bukowski said, “there’s a bluebird in my heart that wants to get out but I’m too tough for him, I say, stay in there, I’m not going to let anybody see you.”

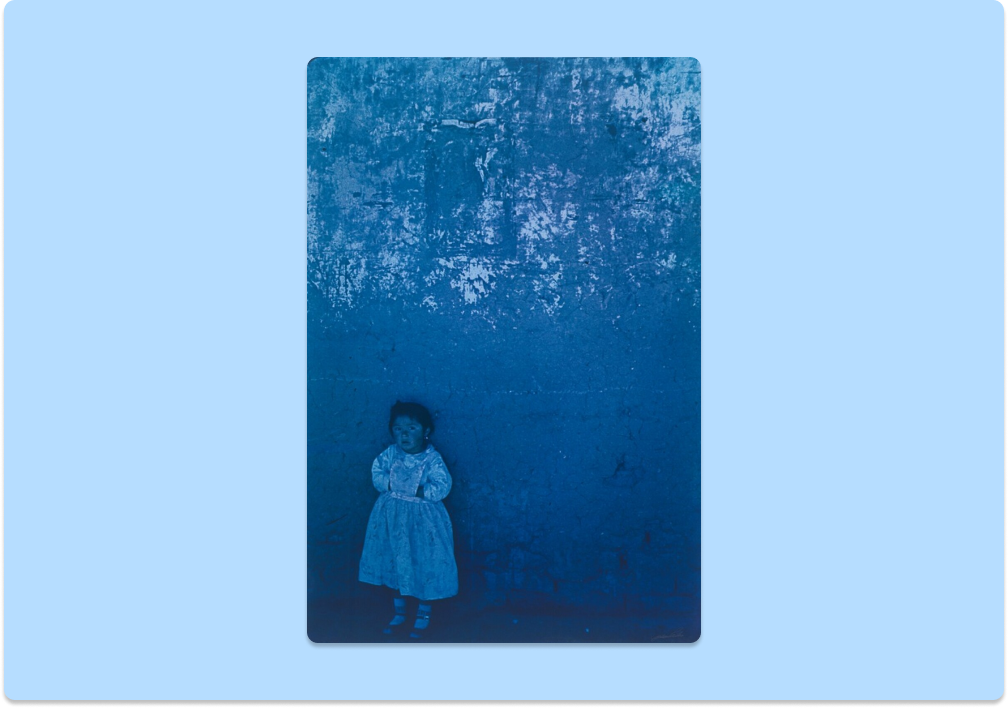

Morgan Parker explores this sentiment in her beautifully written essay, Love Poems Are Dead, where she writes, “Maybe you have to feel safe to fall in love. Maybe you have to be able to have the privilege to ignore everything else.” On a grand scale, love is a privilege we seem to lack. For now, we are working to feel safe in our own skin, break free of bodily shame, and overcome political oppression, so that later we can feel safe undressing the armor of the heart. Parker says, “This is not a world for love poems. I wish it were. I wish my heart could feed a love poem, but this heart needs convincing to walk outside.”

Since the advent of the digital age, our ability to carry out loving relationships seems to be steadily breaking down. In this hyper-digitized, dystopian present we are more single, more disconnected, and lonelier than ever before. I’d like to think that as the pendulum continues to swing (as it always does; the only constant being change) we will come out on the other side having expanded our capacity for love, despite social media depicting an alarmingly diminished capacity to fulfill each other’s needs for connection, warmth, and intimacy. Sara Teasdale’s famous poem “I Am Not Yours,” written one hundred years ago seemed to foreshadow this growing trend of reluctance to contort ourselves to fulfill the needs of the Other, all the while yearning to be lost in the entanglement: “I am not yours, not lost in you/ not lost, although I long to be/ lost as a candle lit at noon/ lost as a snowflake in the sea.”

Perhaps it’s true that “we have been poisoned by fairy tales” (Anais Nin). Perhaps to believe in the love poem is to believe in happy endings and that isn’t a thing we can bring ourselves to do at this moment. To many of us, this world is a dark place, especially depending on where you reside as you read this, in light of recent election results not only in the U.S. but nearly everywhere around the globe. Perhaps this shift away from the sentimental is the acknowledgement that we don’t want saccharine consolations or anodyne; we want to lean into the ways in which the world suffers and for poetry to act as a mirror for the parts of our society in need of fixing so that we can one day feel safe enough to love each other again, and to write poems about it. Even Leonard Cohen, toward the end of his life, focused less on love and sex and more on sociopolitical commentary with songs like, “You Want It Darker.”

Far and wide, poetry has become a space for therapy and social activism, a symptom of the important work there is to be done and our readiness to do it. It might be a symptom of our times that we have too many pressing priorities to write of love. Our proverbial plates heap with anxiety, rage, and a collective sense of impending doom, tipping the scale in favor of hypervigilance over yearning for intimacy. We have become less willing to let our guards down to sweet and frivolous emotions. Instead, we have placed the heart in a pickle jar while we gather recipes for self-preservation in times of apocalypse and now we wait in our self-made bunkers. But is saving it for later our best survival strategy when it seems we could use the nourishment now?

Poetry is first and foremost a container for our emotions that allows it to be a vehicle for empathy. When done well, poems allow the reader to share the emotion of the poet. This is the beauty of love poems—they exist for the purpose of letting the reader bathe in the experience of being in love. There lies a lot of untapped value in this power for getting us through dark times. No other art form is able to transport the reader into the shoes of the subject in quite the same way that poetry can. In an epidemic of emotional disconnection and a society rampant with individualism, poetry has the power to draw us closer and it is this ineffable quality we seek from it. Our evolution as a species, in our desire to grow wiser, seeks answers to problems bigger than ourselves and the biological imperative to couple up, we have to begin with the self, and then in the same breath we have to transcend that very separateness of The (capital S) Self, the illusion that we are not bound to each other, that we do not share the same breath, that in learning to love ourselves we are actually learning to better love each other.

III.

But love is not just a destination or an end to a means. It is also a way of making life’s pain and suffering bearable; it is a way of helping us endure, especially in dark times. Love has motivated the greatest works created in human history. Of all that makes us human, it is this idealism that drives our social and political poetry today that is the very same idealism that wants to believe that love will always be alive.

Love is an emotion that requires a safe place in which to exist. So, an update may be needed to help bring love poems into the space of the present. But there is also something paradoxical in the feeling of love, in our need to be surprised, “swept” off our feet, to “fall,” to be caught up in a “whirlwind.” The idioms used to describe love inform our expectation of an emotion that is not entirely safe, tame, or predictable. The poet must allow the poem to take risks, take us to the ends of the boundaries of the human experience. Like a rollercoaster ride, we must have an innate sense of safety to undertake risk. Somewhere in the gap between these contradictory needs for safety and recklessness is a space rife for exploration with pen and ink. How do we reconcile this craving for the unexpected in a world that feels untenably uncertain? How to free an emotion so heavily written about from the sand trap of cliché? And how do we find something new to say about a universal, timeless, and unchanging notion such as love in a world that is so changed?

I think the fact that there is no comparable contemporary equivalent to the likes of Rumi and Leonard Cohen means that, when we’re collectively ready for it, there is a whole market lying ready to be updated, modernized, and explored. I predict that in the coming decade(s) we’re going to see a revival of love in poetry. Perhaps that is a sign that my internal optimist, while on life support, is hanging on. Don’t get me wrong, I am an avid consumer of heartbreak, sex, and political poetry. I, like many others, had waited my whole life to see these conversations take centerstage in the mainstream and I am here for the pearl-clutching, convention-bucking, tradition-questioning, self-celebrating poetry—I’ll take them over any shallow rom-com any day of the week. There are few things more satisfying than watching us collectively break out of the prison of our own molds, but I admit I also want the love back.

I long for poetry that helps us fall in love with each other all over again and I long for a world where it is safe to do so. I want to know that love is still the driving force behind so much of our striving. To be swept away in a well written collection of love poems. To believe, especially as we navigate a world filled with robots and billionaires who prioritize space travel over solving world hunger, that our human capacity for loving one another is only growing, that our hearts are bigger and stronger than they’ve ever been, that they exceed anything that their bionic counterparts can ever stand to, that—as cheesy as it sounds—our hearts still beat as one, so that if aliens ever pick up the radio signal of Earth, they will hear the sound of a collective heart open to love and know that we are the planet where it exists, where it always will.

.png)

%201.png)

.png)