Sweet Elsewhere #3: Not This One

Matthew Vollmer's third essay on the inevitability of failure in the pursuit of publication and the importance of not giving up in spite of all the rejection letters

As I continued to submit to literary magazines, the self-addressed envelopes continued to appear in my mailbox, and because of my inexhaustible reserves of dumb confidence, I always thought, right before I opened one: this –this could be the one. But each envelope always only and ever contained a new form letter, printed on those small, rectangular slips of paper—in various shades—that were becoming like disappointing souvenirs, a collection of little flags of defeat.

Giving up, though? Not an option. Every rejection was another nail I pounded into the resolve of my unyielding determination—or whatever. I had no idea what the editors of Turnstile or Open City or The High Plains Literary Review thought of my stories, but I liked to imagine that the words I’d typed onto my laptop screen and printed out and sent hundreds of miles away had entered the brains of somebody. I hadn’t found “elsewhere” yet, but I was receiving pre-printed messages, presumably stuffed into the self-addressed, stamped envelopes by other human beings, and thus my existence had been however obliquely acknowledged.

Even so, I don’t ever remember being all that troubled by receiving them—at least not in the beginning. I expected to be rejected… until that day came when I wasn’t.

And that was, I told myself, only a matter of time.

Maybe I didn’t mind because the world had opened itself to me, and that felt like true enough progress. After having spent my entire academic career—from first grade through my sophomore year of college—in the care of Seventh-day Adventist teachers, I’d transferred to the University of North Carolina, explicitly to study English, and specifically creative writing. I’d survived the workshop gauntlet: in order to progress from one class to the next and arrive at your final capstone, you needed professor approval, and all of my teachers—a guy who’d written a novel about an Elvis impersonator and then, at the suggestion of an agent, actually taught himself to be an Elvis impersonator, and wrote a memoir about it; a woman whose bio always included the novel she’d written that’d been made into a TV movie; and a crinkly, sharp-witted old Presbyterian woman from Iredell County who had Flannery O’Connor Main Character energy—had praised my work. Furthermore, I’d submitted a story to the Louis D. Rubin Award, which honored an outstanding student of fiction by a senior, a a story titled “Illuminations,” in which a little girl is struck by a lightning bolt during a spring thunderstorm but is miraculously revived once the chalk painting—a reproduction of Tintoretto’s The Resurrection—dissolves in the rain and bleeds into her dress, much to the surprise and dismay of a group of people witnessing the event.

I had worked hard on this story: day after day, hour after hour, polishing, editing, shaping each sentence and paragraph so that the words fit together, images brightening, dialogue intensifying. Like slowly and diligently chiseling from shapelessness a voluptuous form. I knew I would win the Louis D. Rubin Prize. And I did.

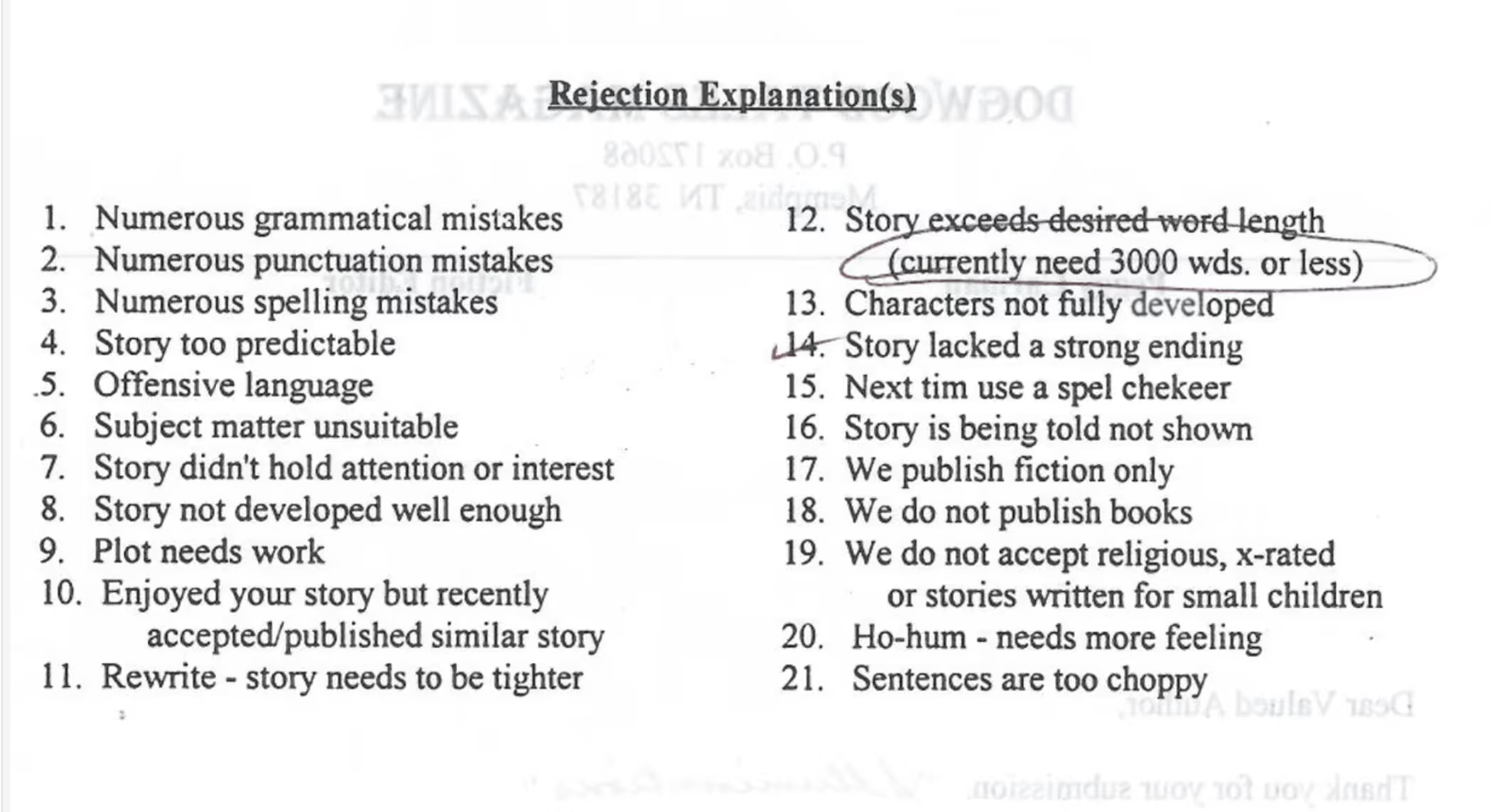

I sent “Illuminations” out to a variety of literary magazines, all of whom rejected it: for whatever reason, I only kept the letter that Dogwood Tales Magazine sent me—an 8 x 11 page, a size that suggested the communiqué was somehow more official—and that instructed me to refer to the “enclosed rejection form,” which I reproduce here:

I knew my story wasn't bad—after all, it had won an award at my university, and thus proved, or so the powers that be claimed, that I was 'outstanding'—but in the eyes of Dogwood Tales Magazine, it was simply 'too long' and 'lacked a strong ending.' Their rejection came with a checklist: a taxonomy of failure rendered in efficient little boxes. There was something almost comforting about that checklist, as if the editors had seen so many manuscripts, endured so many writerly sins, that they'd managed to categorize every possible way a story could go wrong. My story wasn't 'predictable' or 'ho-hum.' At least it hadn't been 'too predictable.' At least my characters hadn't been deemed 'not fully developed.' The checklist suggested a kind of editorial omniscience—here were people who had stared into the abyss of bad writing for so long that they'd mapped its every contour. Length I could work on. The ending I could revisit. I'd been told by my mentors and friends to trust the process. And so I did.

Back in the day, I spent hours at UNC's D. H. Hill library, searching New Yorker archives for old, uncollected J. D. Salinger stories. I listened to space rock and alt country. Lived off cereal and microwavable foodstuffs. My teachers were mostly geniuses, except for the Shakespeare prof—a ruinous old jackass who claimed we only cared about “Mickey Mouse” and delivered brutal fill-in-the-blank quizzes. But there was the 17th century lit teacher who paced back and forth, delivering lectures with such passion I couldn't help but wonder if he'd done a bump of coke before class. And the creative writing professor who praised a story of mine where the main character shot a Jack O’Lantern with a shotgun for its “fecund masculinity,” thus validating me as a legitimate storyteller—one with “themes” and “symbols” and everything.

I loved these teachers. But inside, I was miserable.

My main problem—compounded by smoking too much weed—was that, aside from my roommate and a few people from creative writing workshops, I had very few friends. I lived in a dark, dank apartment on the edge of Carrboro, feeling like an imposter whenever I walked the streets of Chapel Hill or went to shows at Cat's Cradle. I'd sit on a concrete cube outside Greenlaw, home of the English Department, smoking cigarettes and watching hordes of students who, I imagined, were all similar in that they hadn't been raised Adventist like me. I found ways to dismiss them all: the slouching indie-rockers bobbing across the Quad on waves of lo-fi irony; the visual artists with their face-piercings dissing Duchamp; the Euro-trashy intellectuals flipping dramatically through de Man over quadruple-shot mochas. I rejected them all before they had the chance to reject me.

Time passed. I graduated. Drove my '87 Nissan Maxima to Wyoming, where I spent the summer at Old Faithful Inn, drinking honey raspberry craft beer and hiking the Tetons. Took the long way home: Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, L.A. Then landed the worst job I've ever had, working for an ill-tempered public defender who, thanks to a bout of childhood polio, limped around the office like a foul-mouthed pirate, barking insults at us all.

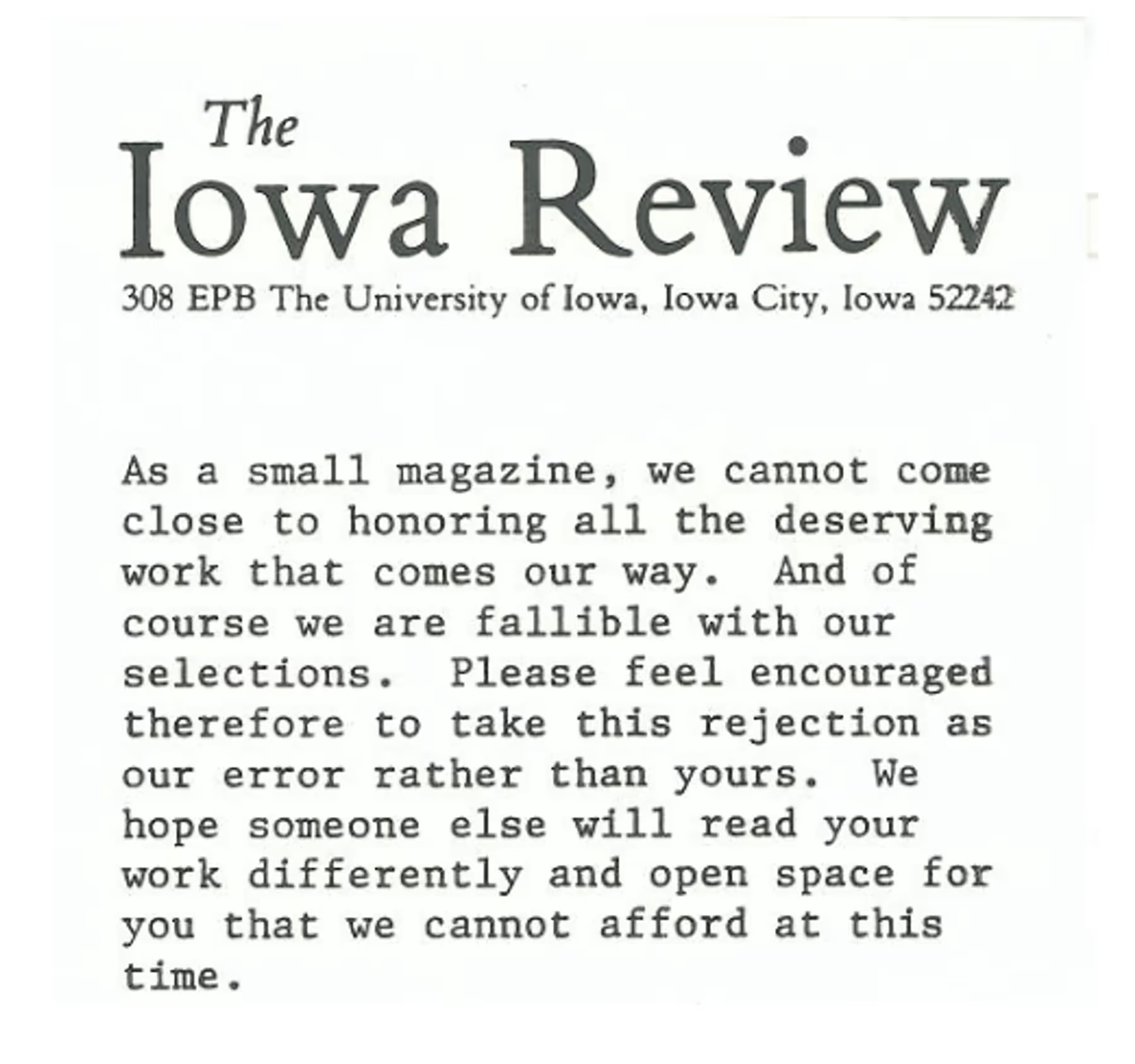

It strikes me now that small town lawyer could have learned something from literary magazines - their art of the gentle letdown, the way they could crush dreams while somehow leaving them intact. There’s a beauty to the form rejection; the best ones unfold like eloquent apologies disguised as encouragement and—sometimes, as with the case of The Iowa Review circa sometime in the early 2000s, self-deprecation:

(Geez, Iowa Review. That almost made me feel a certain way.)

As a genre, the form rejection is instantly recognizable. Pithy, graceful, versatile, clean. Often general enough to serve diverse audiences. Able to deliver crushing disappointment with minimal effort. The rejection note is a curtain preventing your entry and however delicately embroidered you can't see through it. Its language has evolved into a precise taxonomy of dismissal - from the brusque “not for us” to the encouraging “please submit again.” Like pressed flowers between pages, these notes preserve moments of literary aspiration suspended in perpetual almost. Yet there's something democratic about their ubiquity: even Plath's first submission of “The Colossus” was met with one of these pristine barriers, these polite bouncers at literature's most exclusive clubs.

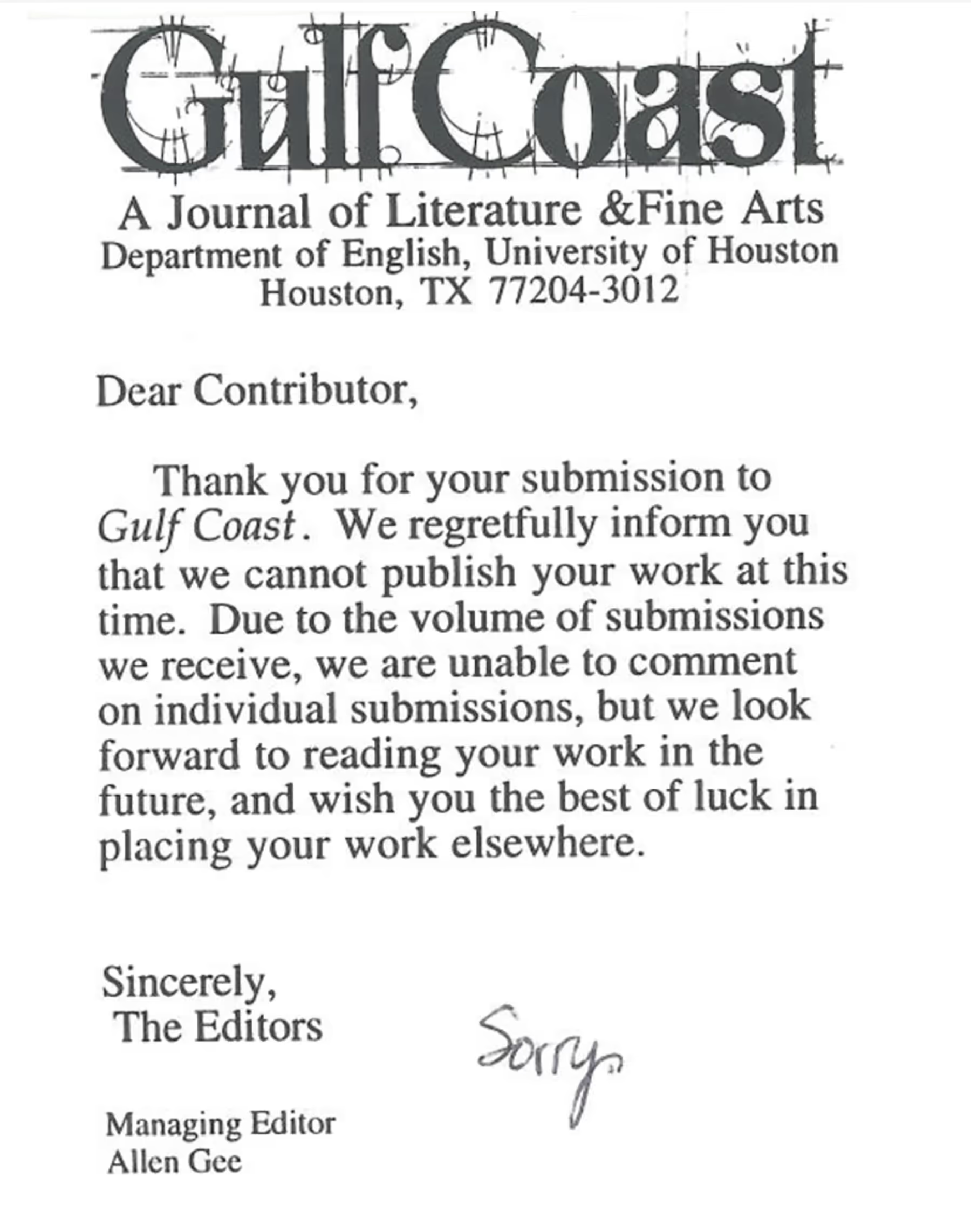

At some point in my submission process—I don’t know when, exactly, but certainly after several years—actual human handwriting began to appear in the margins and white spaces of the form letters I received. An anonymous reader at Gulf Coast felt compelled to write a wobbly “Sorry”:

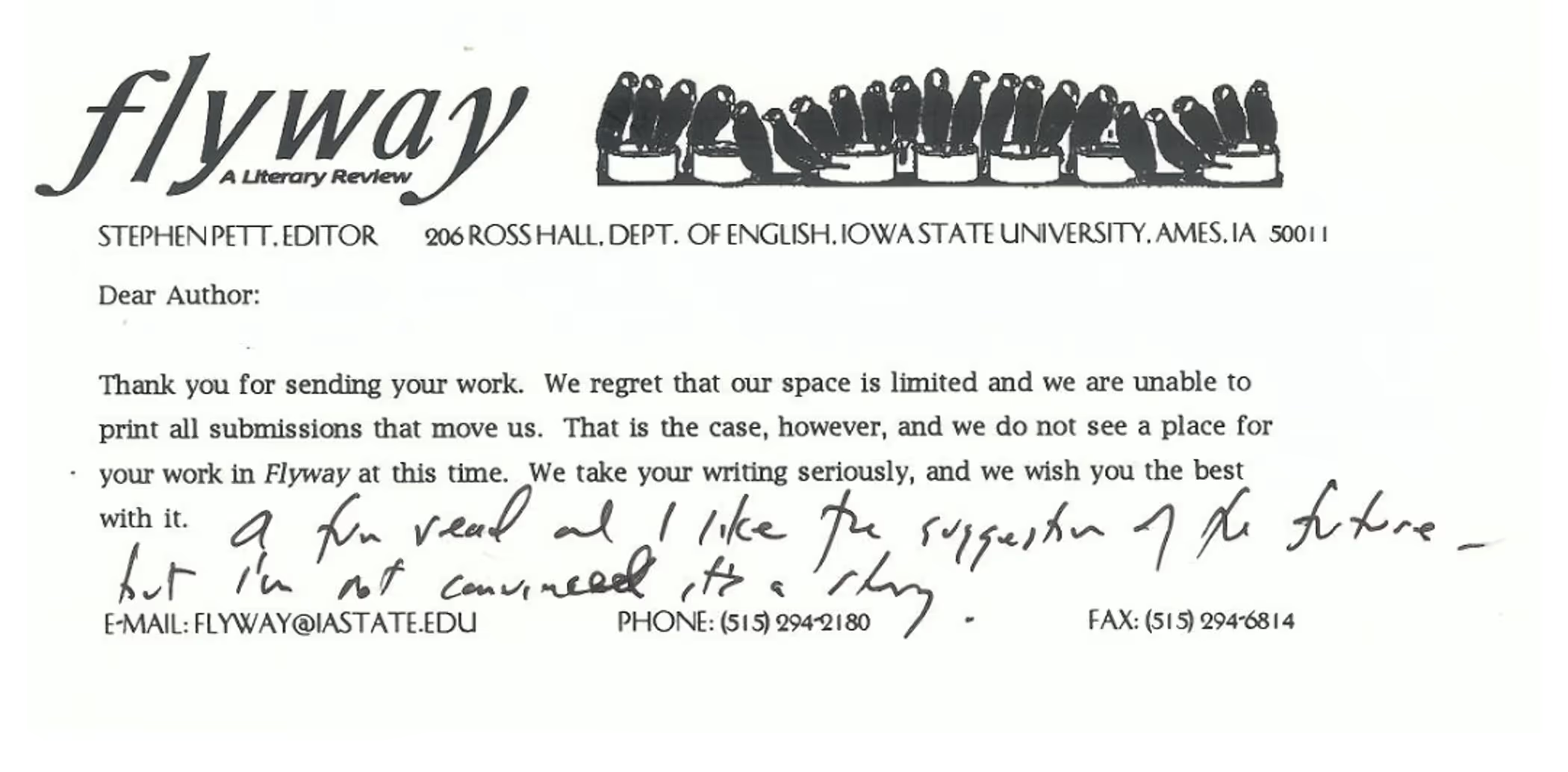

Flyway: A Literary Review, claimed that my story was “a fun read” and that they “liked the suggestion of the future” but weren’t convinced it was a story.

Jack Smith, editor at Green Hills Literary Lantern, said, “Sorry to be so late—got behind,” an expression of vulnerability I found somewhat endearing.

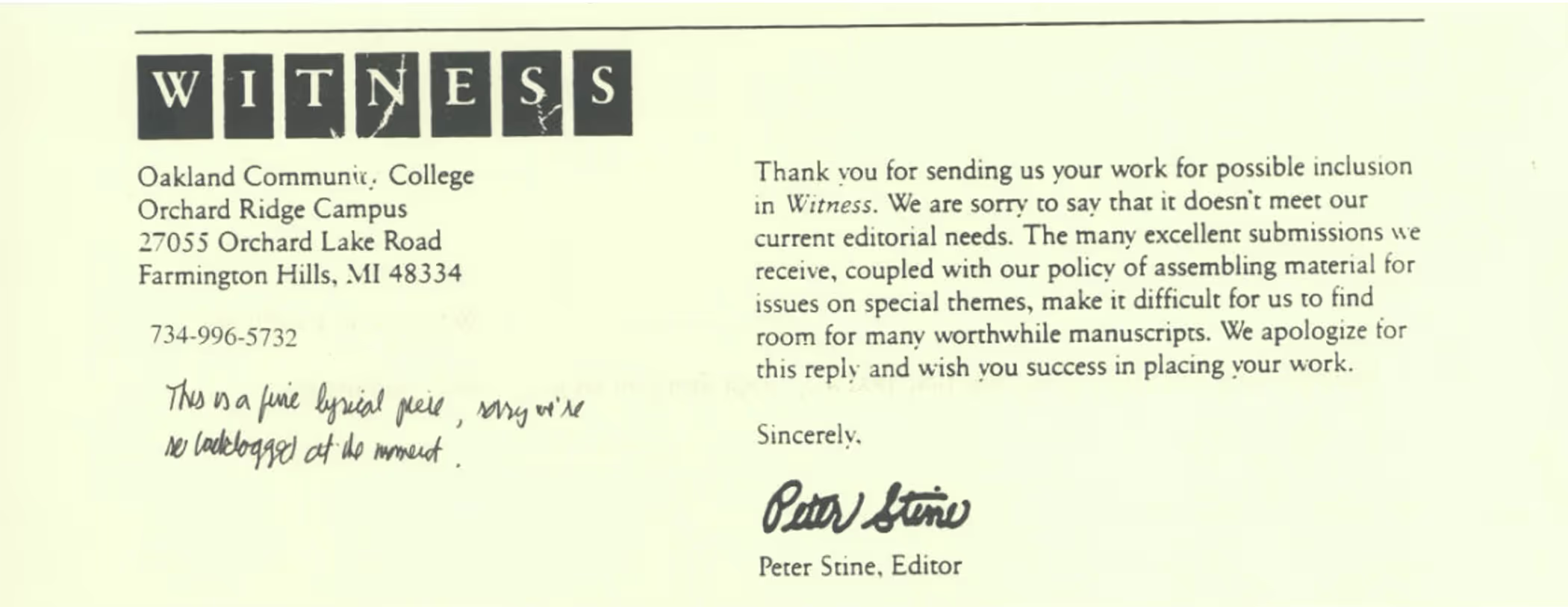

Peter Stine, at Witness, wrote to say, “This is a fine lyrical piece. Sorry we’re so backlogged at the moment.” I liked “fine.” I liked “lyrical.” The only reason he said no, obviously, was a literary log jam. Had I sent the story sooner, would he have said yes? Was I getting closer?

Well, since THERE WAS NO WAY TO KNOW FOR SURE, I just shrugged and told myself the answer was of course.

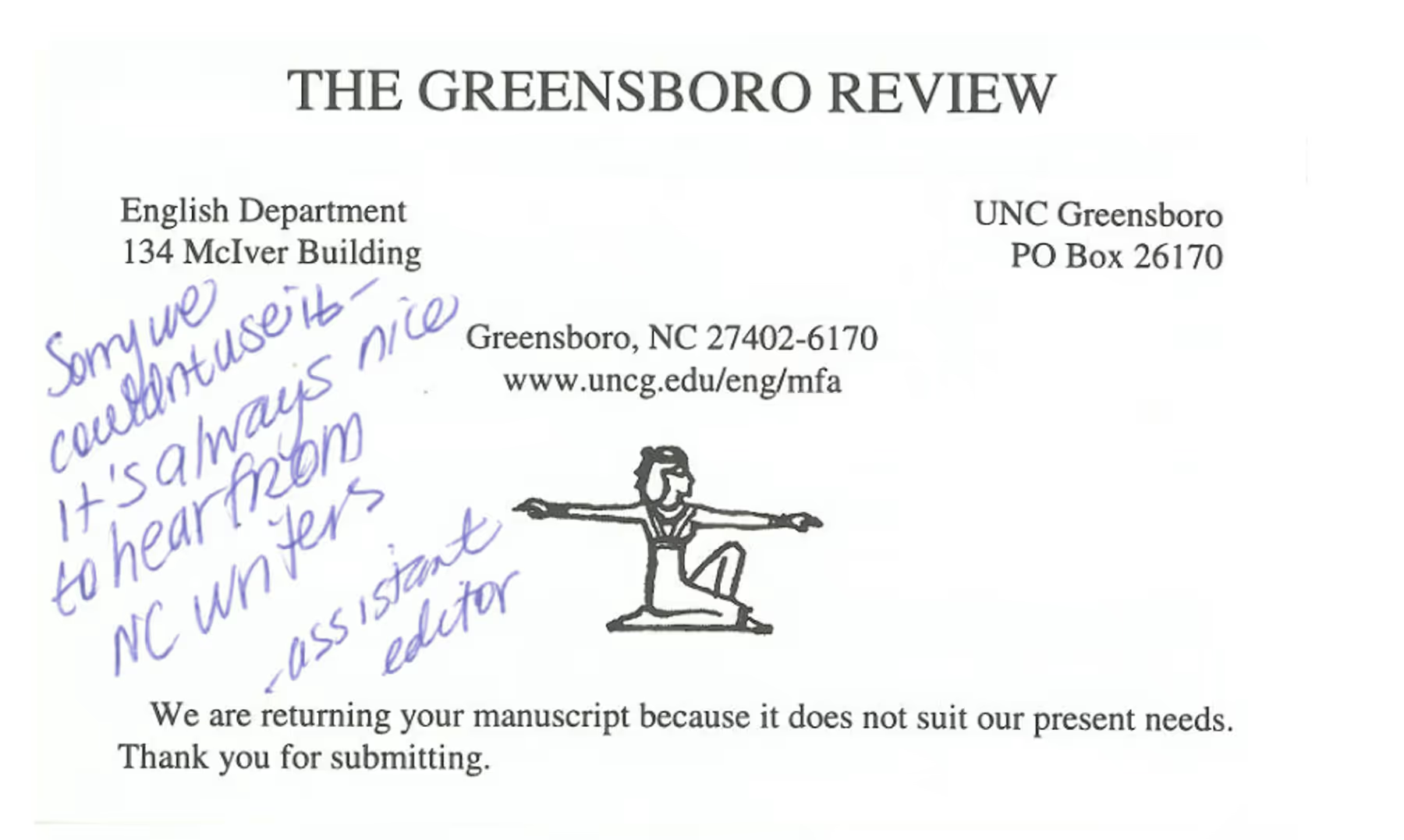

The Greensboro Review assured me that it was “always nice to hear from NC writers,” which was maybe a sweet thing to say but likely would have felt kind of vapid to a young writer who, having been exiled from popular culture and society by the strict fundamentalist religion in which he’d been raised, didn't want anything to do with “regional” writing. The very phrase conjured up images of blue-haired ladies in dusty independent bookstores, clutching their signed copies of Lee Smith novels to their bosoms, cooing over any author who could properly render the preparation of a chess pie or capture the exact timbre of their great-aunt's gossiping on the wraparound porch. These were the same women who'd corner you at literary festivals to tell you about their cousin who'd written a ‘delightful little book” about growing up in Hendersonville, and wasn't it just wonderful how our Southern stories still spoke to people? I wanted no part of that provincial embrace.

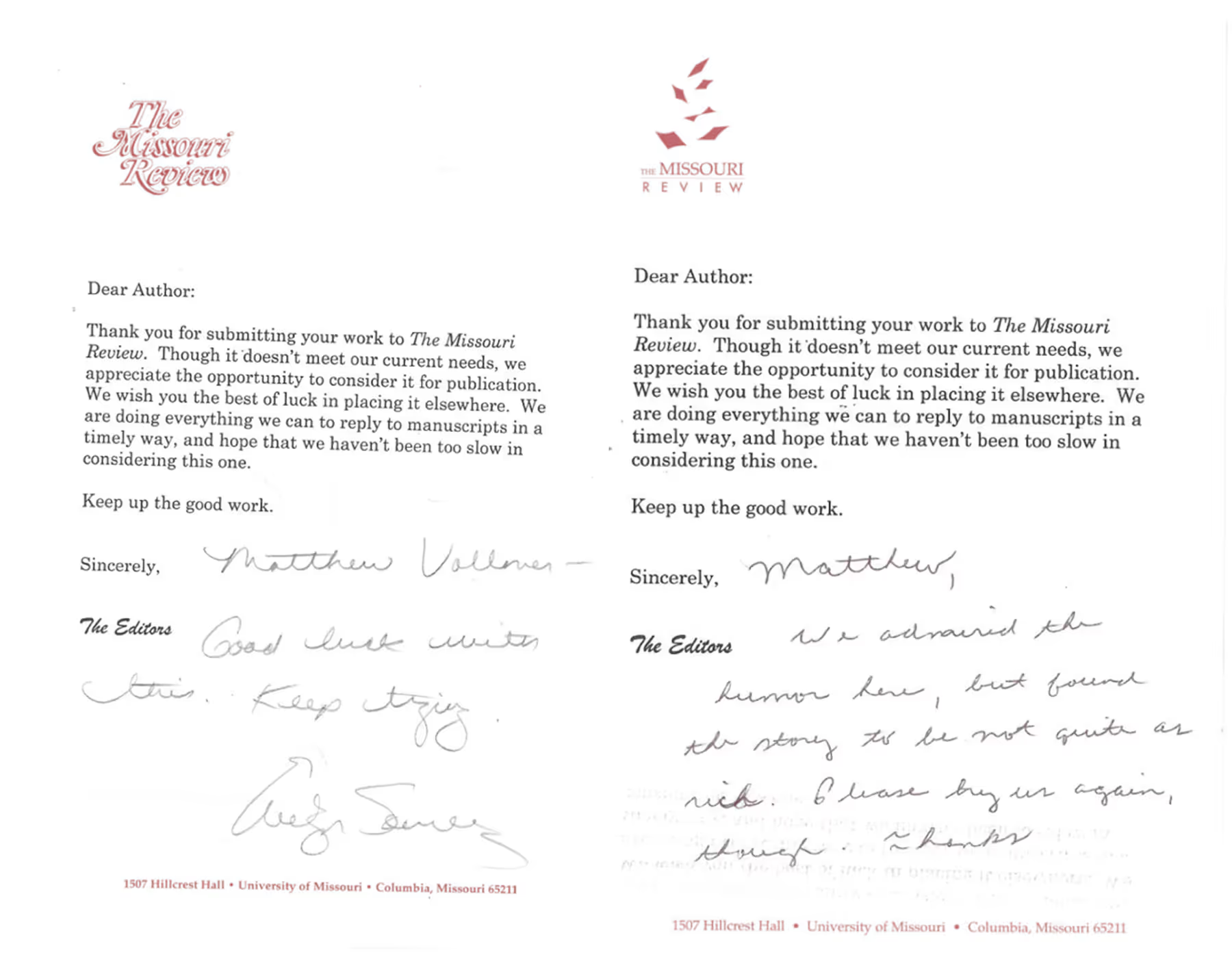

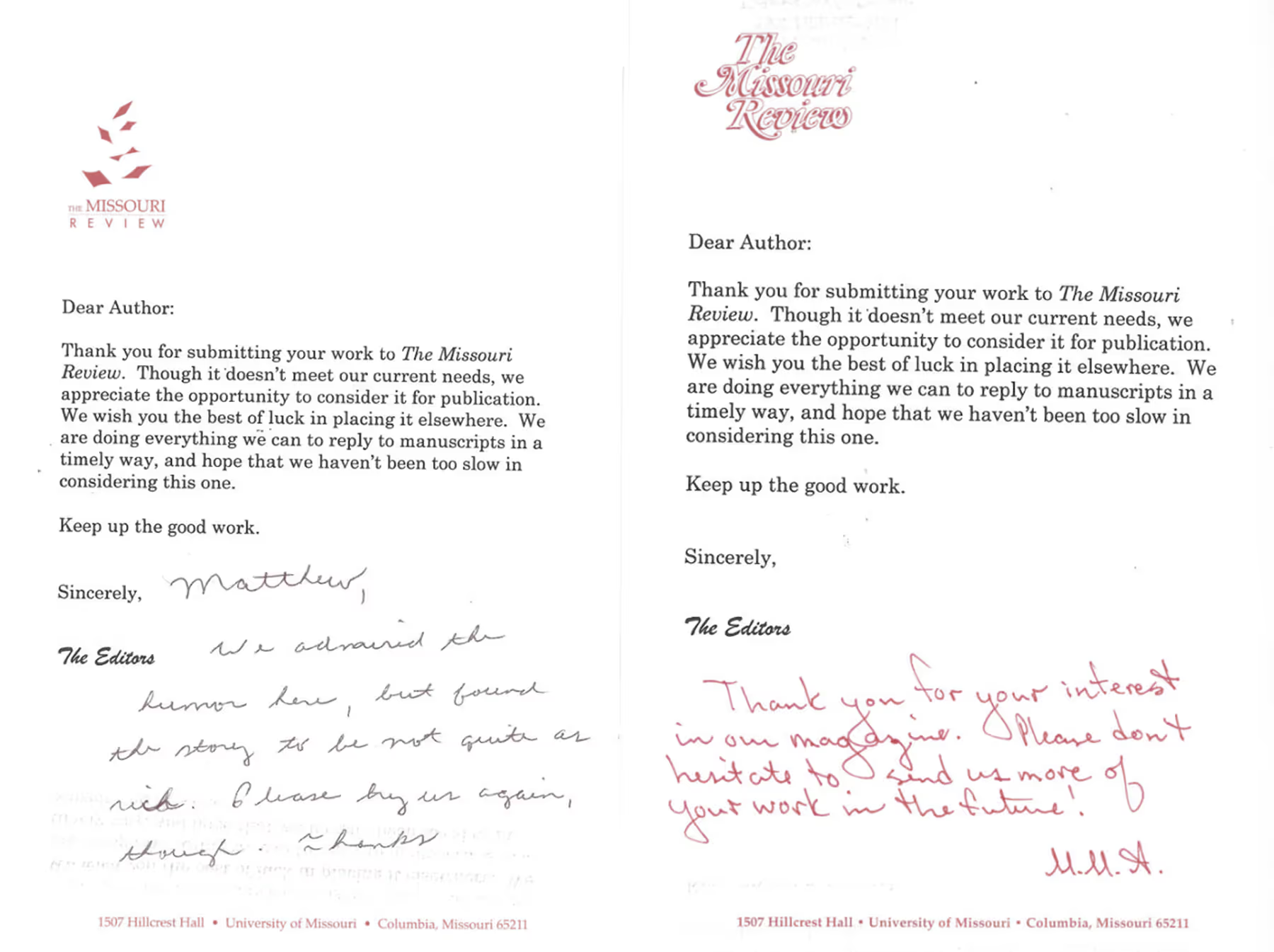

The number of rejections I received from The Missouri Review suggests I must have really wanted to be published by that magazine, though—spoiler alert—I never was. Encouragement abounds in these rejections—“good luck with this,” and “we admired the humor” and “don’t hesitate to send us more”—but the handwriting that accompanies these rejections suggests a different reader each time. How many readers did The Missouri Review have, anyway? Did they have a mandate that each submission receive an obligatory note? Does that explain the large amount of white space on each rejection?

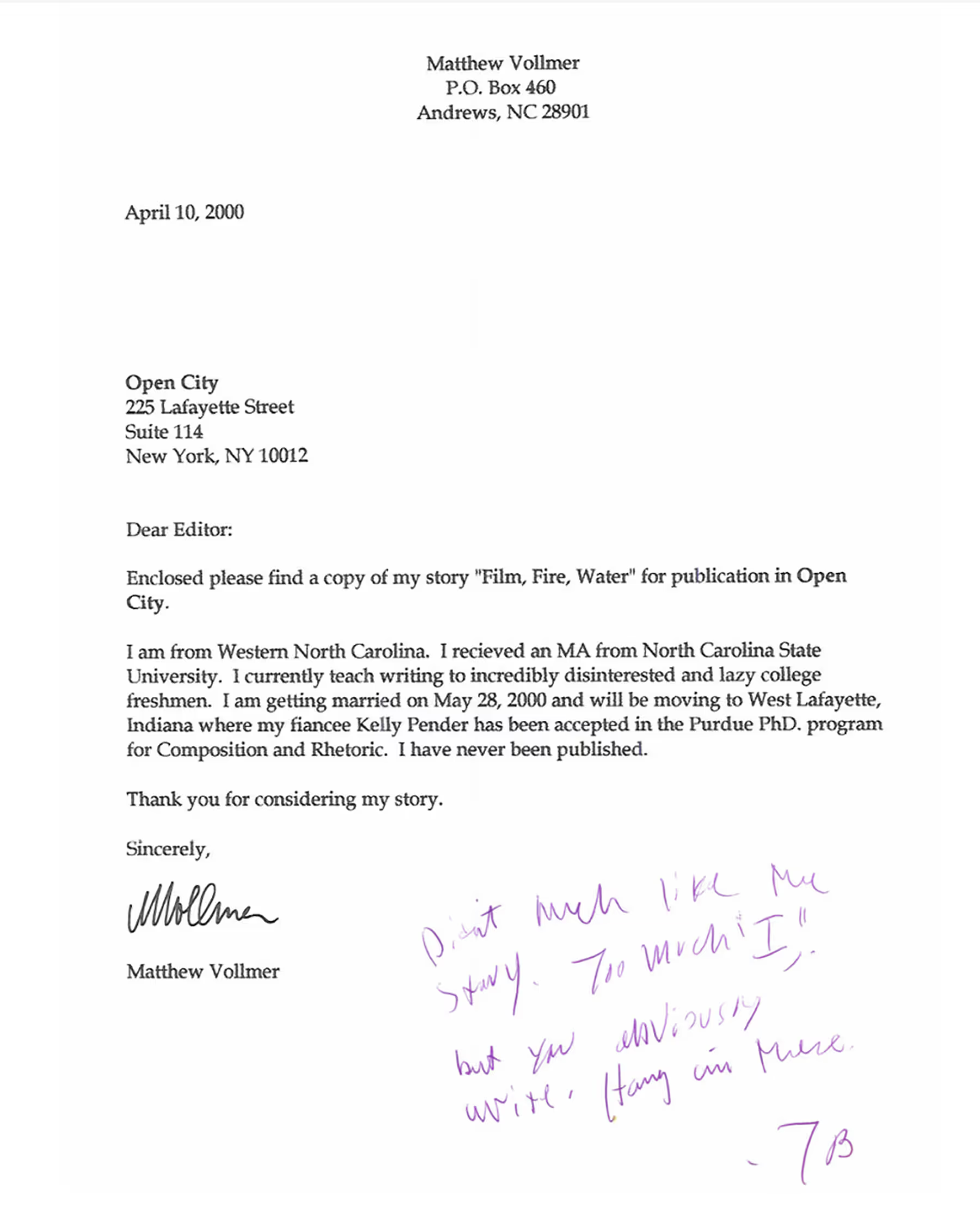

Apparently, some places didn’t bother with form letters at all. As in the case of the now defunct but once quite popular New York literary magazine, Open City, which sent my cover letter—which seems to me now a kind of desperation disguised as cool detachment: who else includes such details as “I currently teach writing to incredibly disinterested and lazy college freshman. I am getting married on May 28, 2000 and will be moving to West Lafayette, Indiana where my fiancée Kelly Pender has been accepted in the Purdue PhD. program for Composition and Rhetoric. I have never been published.” Somebody at Open City with the initials “TB,” wrote back to say, “Didn't much like the story. Too much 'I.' But you obviously write. Hang in there.”

Did I know at the time that those initials likely belonged to Thomas Beller, who, with Daniel Pinchbeck, had started the magazine nine years previously, and was kind of a big deal? What did I even know about Open City at the time, other than the fact it was cool and urban and published the likes of Sam Lipsyte and the poet David Berman, of Silver Jews fame? Probably not that much, though I’m willing to bet I bristled at “didn’t much like the story” and reread “but you obviously write” over and over for the little dopamine hit it would have given me, and definitely took the brotherly advice of “hang in there” to heart.

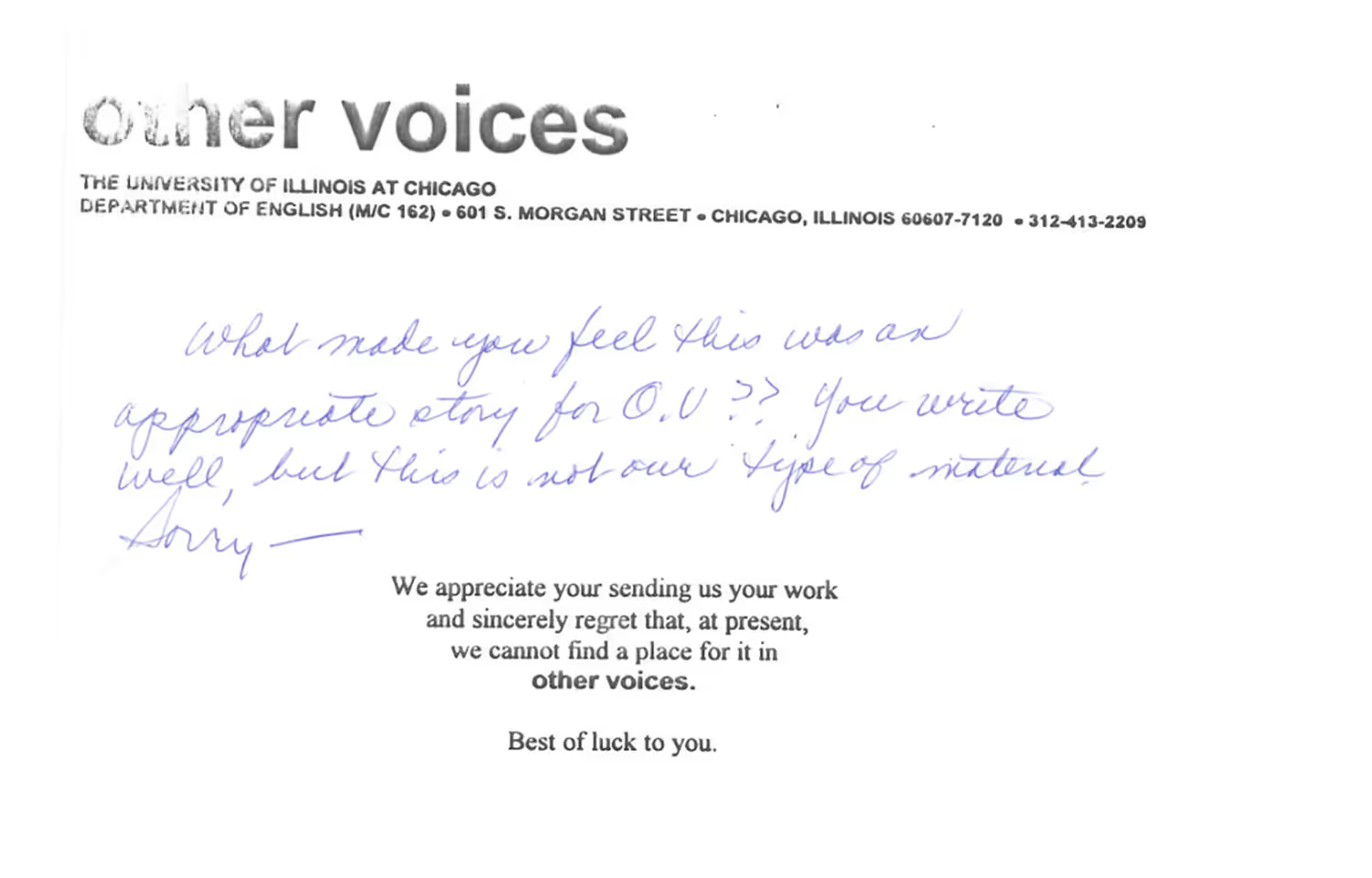

Other magazines, like other voices, seemed simply not to give a fuck. “What made you feel this was an appropriate story for O.V.?” wrote an anonymous hand. “You write well, but this is not our type of material? Sorry.” I remember the story I sent other voices. It was titled “If Time Lasts,” and was structured using anaphora: each section began with that phrase, which was one I heard a lot from my father, a Seventh-day Adventist that used it somewhat euphemistically to refer to the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. “If time lasts and you get married and have children of your own,” my father might say,

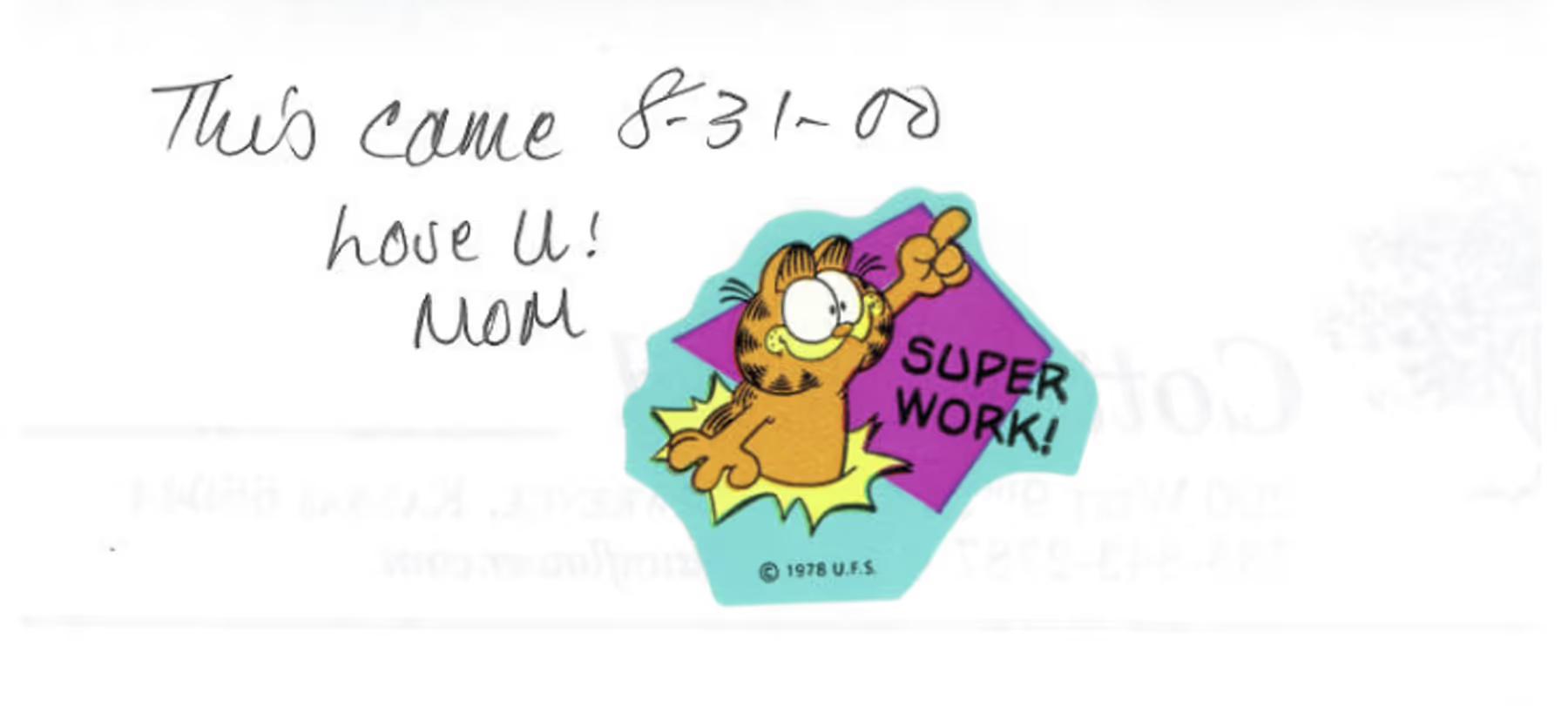

On the back of one rejection—sent to my parents’ address, as I had launched rejection letters while in between addresses myself—bears a Garfield sticker that says “SUPER WORK!” and my mother’s handwriting: “This came 8-31-00, Love u, Mom.”

Thanks, Mom. I know you didn’t mean to make it worse.

But you did.

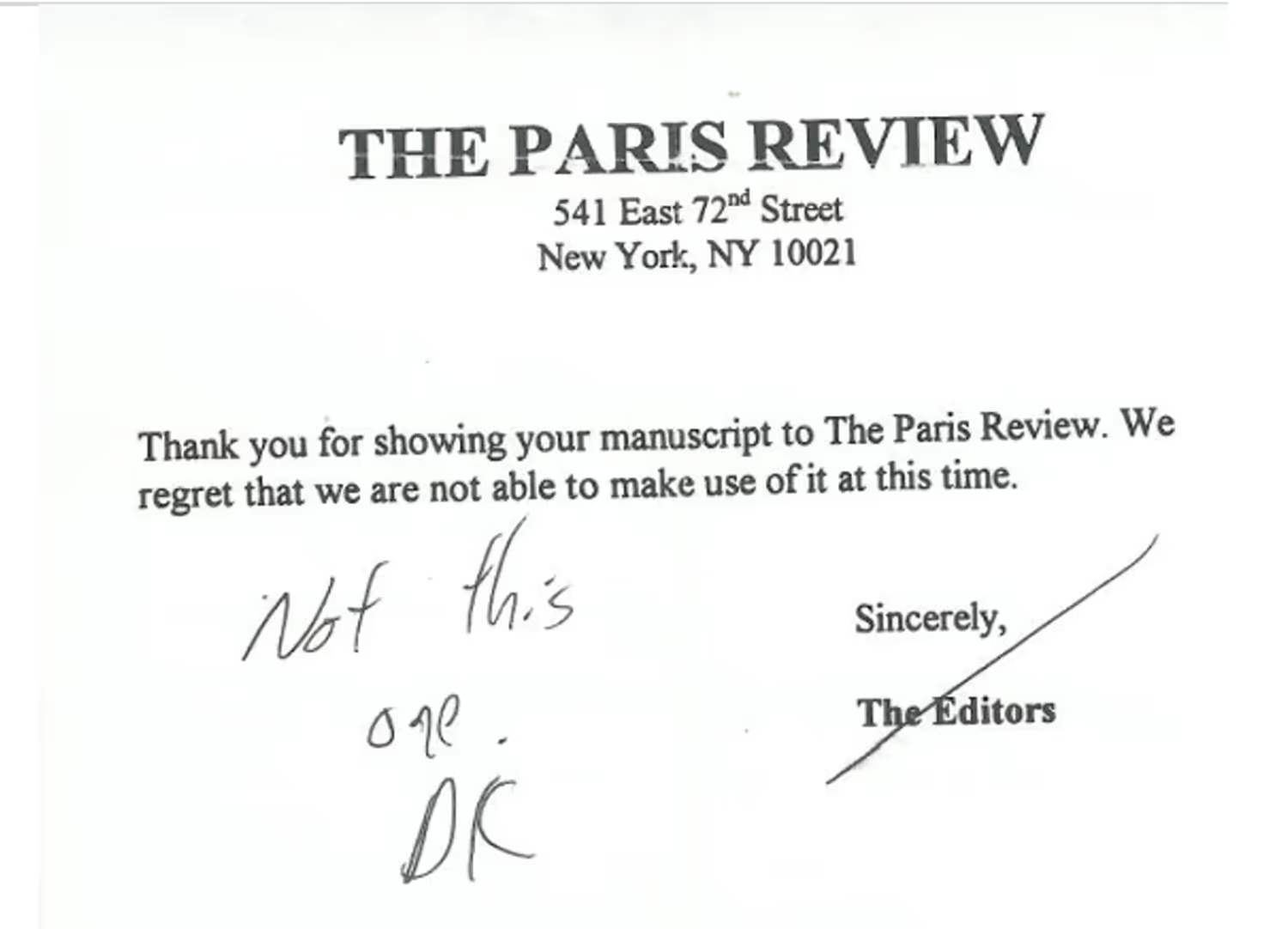

But then a rejection from The Paris Review came in the mail for me and I started to feel like it had all been worth it.

“Not this one,” it said. Signed: “DK.”

Who was “DK”? Daniel King? Dean Kensington? Darnell Kobra? It hardly mattered. Someone with the initials DK had read my story, struck through “The Editors”—a decisive slice that seemed to confer authority—and said, “Not this one.” Was DK some kind of Paris Review Overlord. Whoever they were, they knew something about the power of words. Of economy. Not this one, meant, obviously, that DK suspected, based on the strength of the story they were rejecting I had another, better one. I had tried to get away with something by sending the story I had. And like a code he knew only I could translate, a negation became an invitation. I’m turning away this one, DK suggested, because I know you have something else. Something better. Don’t hold back. Keep ‘em coming. It’s only a matter of time.

Yes, DK. It will be my pleasure to keep them coming.

A pleasure indeed.

.avif)

.avif)