Sweet Elsewhere #6: Hide & Seek Champions

Matthew Vollmer's sixth essay in the series dealing with rejection and perseverance in the literary journey, writing as an outsider, and processing failure

I did not believe my wife Kelly, who, in February of 2002, told me she was pregnant. It wasn’t that I didn't know the so-called “rhythm method” wasn't foolproof; it just didn’t seem—from my admittedly limited perspective regarding the complexities of female anatomy, to say nothing of my knowledge about the inner workings of pregnancy tests—likely. I had no reason to believe that the window of the little wand she’d peed on had any reason to deceive us, but also? I had no reason not to. So I didn’t. Unsurprisingly, I was wrong. And once I had accepted the truth—that, in a matter of months, supposing everything went according to plan, my wife and I would be paying a visit our local hospital and returning to our apartment with a real live human person who we would need to take care of and love for the rest of our lives—I realized one thing: I had to approach my writing with more seriousness and intensity than ever; my future child’s welfare depended on it.

It was, I told myself, time to write a novel. Once finished, I would send it to one of the Big Five in New York City. They’d fight over who would publish it, the winner offering a sizeable advance. Coverage in the New York Times would follow. And Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly and Bookforum and all the others. A novel, I knew—especially a successful one—could lead to a tenure track job. To a 401K. To health benefits and a college savings plan for the kid we would meet in less than nine months. I needed to start it soon. Like right now. Like today.

+

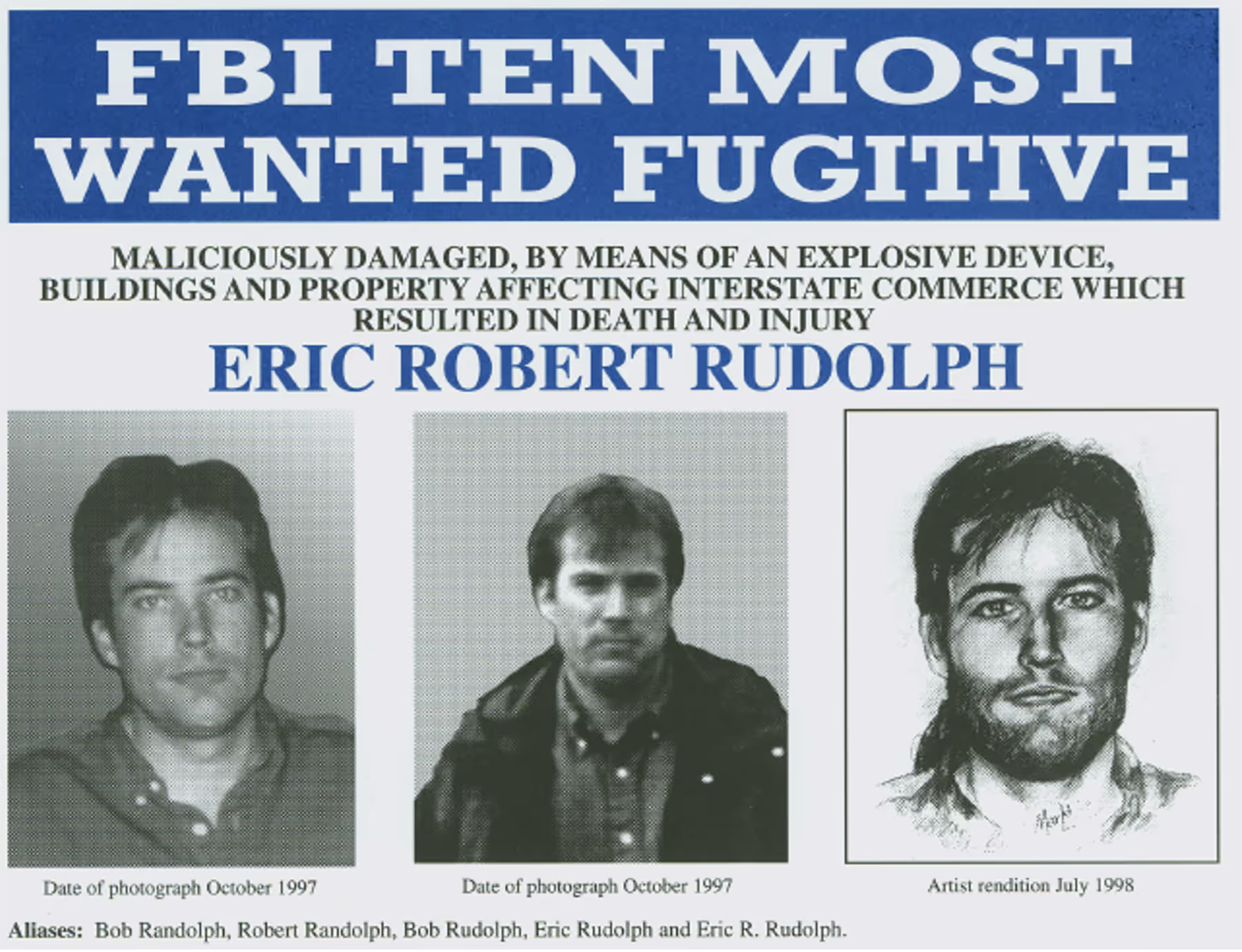

I knew from the very beginning that book was going to be about Eric Robert Rudolph, the neo-Nazi slash white supremacist who, years before, had remotely detonated a series of homemade bombs: one at a lesbian nightclub in Atlanta, another at an abortion clinic at Sandy Springs, and another at the Olympic Park during the games in 1996. These bombs had killed several people and injured a great deal more; one woman—a nurse at one of the clinics—had survived dozens of nails being shot into her face.

While it might seem that I would have little in common with a man who had lived for five whole years at the top of the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list, I had felt a weird kinship to Rudolph. Not because we shared any core beliefs. I wasn’t “pro life.” I wished everyone, regardless of their sexual orientations, the best. But Rudolph had grown up not far from my hometown, high in the surrounding mountains, in a place whose name I’d heard people say was Cherokee for “Land of the Noonday Sun,” due to the steepness of the mountains and the lowness of the hollows. A place where, in winter, you might only get a few hours of direct sunlight. A place that was wild and dark, and where Rudolph, a survivalist loner, would disappear for days, heading into the woods on a Friday after the high school let out and returning on a Sunday afternoon, wearing the exact same shirt and jacket.

I wasn’t a loner—at least not by choice—but as the son of a dentist growing up Seventh-day Adventist in a tiny town in the mountains of North Carolina and attending a private church school of no more than thirty kids in grades 1-8 and having made zero friends outside of the insular Adventist bubble, I knew something about isolation and about living in a community where nobody seemed to know or care that I existed. And though I was not on the run from the federal government, I had spent my youth imagining the day when representatives from a New World Order would hunt my family and me down, when we’d have to leave our home and flee with other seventh-day-Sabbath-keepers deep into the mountains. Furthermore, as the only person in my family to have left the Adventist church, I felt like I might know what it might be like to live like a fugitive.

+

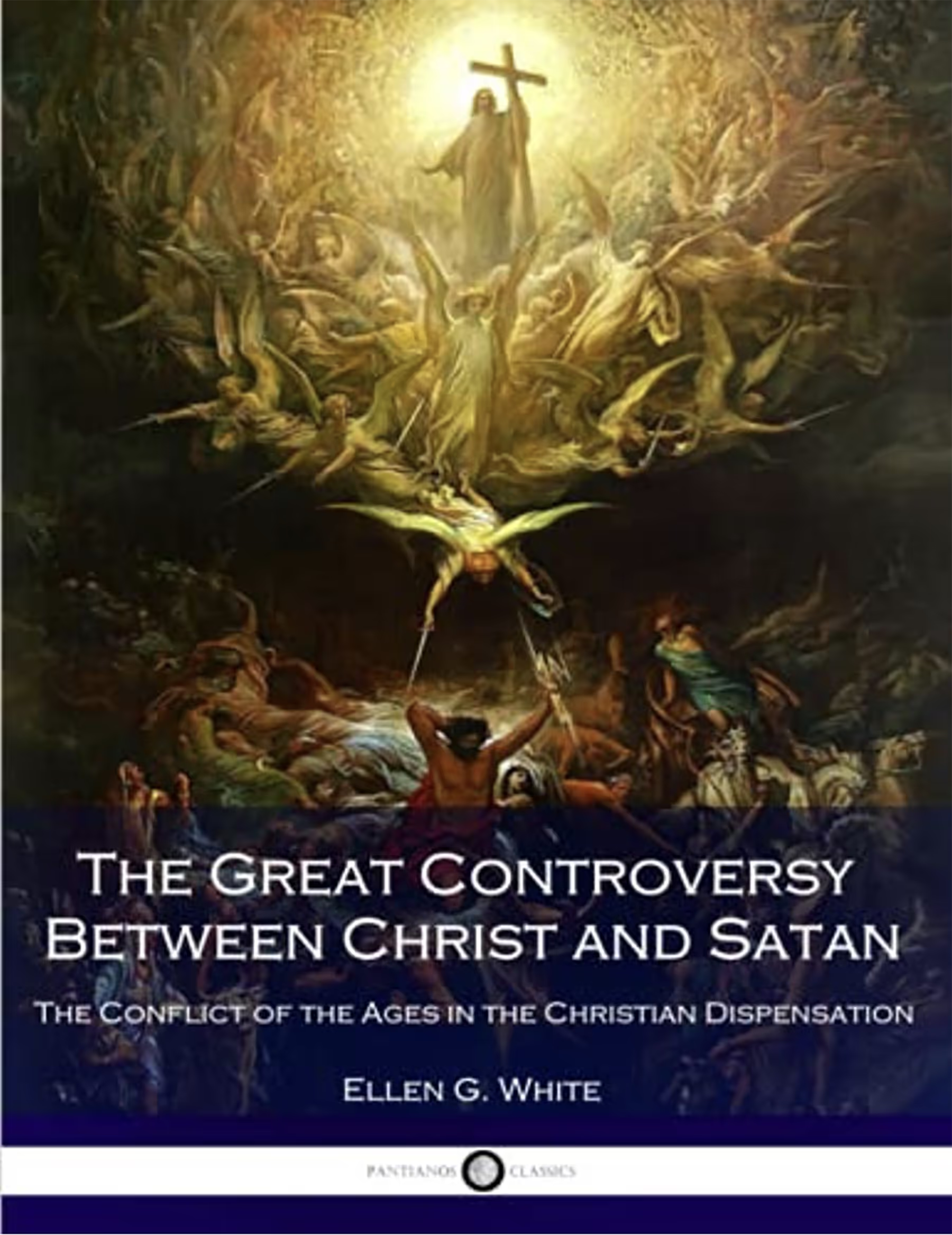

When I was a boy, I often felt sorry for myself because I lived in the middle of nowhere. I didn’t always want to walk through the woods or squat in the creek hunting salamanders. I was often bored. Supposing I had expressed these feelings in the presence of my grandmother, she would tell me that I needed to read the chapter in The Great Controversy on the “Time of Trouble,” a work of speculative fiction the people of my church regarded as prophecy and which predicted that, during the End Times, the Antichrist would decree Sunday to be the true day of worship, thus making us—the Adventists, who worshipped on Saturday—criminals. Presumably, my grandmother’s instruction to re-read this rather harrowing account of what was to come should remind me if I couldn’t handle the small disappointments of everyday existence, I might not be expected to fare very well during the time of the End, when I’d be forced to hide in a mountain cave from would-be persecutors with only the promises of the word of God—which I had been implored to collect in the storehouse of my memory—to keep me warm.

In other words, I needed to revise myself.

I couldn’t help but think: maybe she’s right. I was not the kind of kid who cherished scripture or proudly proclaimed Jesus to be my best friend. I spent most of my time thinking about Tony Dorsett’s 99-yard run or Herschel Walker’s pushup regimen or Michael Jordan’s free throw line dunk. I preferred MAD magazine and Spy vs. Spy and Garfield and The Far Side to the tomes of our church prophetess. I didn’t go door to door telling people about Jesus Christ. I built haunted houses in our basement, hung tarps from the rafters to create passages, instructed my sister when to pull the dental floss that would cause the Coleman cooler to appear to open by itself and reveal a headless doll.

+

I didn’t know where, exactly, my family would go during the “Time of Trouble.” We hadn’t set aside land for this purpose, hadn’t built bunkers or hideaways, and when I discovered that one of our fellow church members stored dried legumes and rice in giant, waterproof barrels in his basement, I wondered if, during those last days, we’d have to beg to share his food. All I knew, really, was that when the one-world government enacted the Sunday Laws, Sabbath-keepers would have to flee to the mountains.

The thing was, though—and I thought about this a lot—we were already in the mountains. I had spent the entirety of my life here, living in a house in a cove at the base of a mountain, on a mossy hill above the intersection of two streams. And, as boring as I often thought it was to live in the middle of nowhere, I had to admit that these mountains were full of beauty, home to secret places that I’d visited and loved: little valleys and coves and hollers, where the sun barely—if ever—reached, places that’d hold onto snow—like a fading memory of winter—for weeks after it’d melted everywhere else, thickets of rhododendron and azaleas so dense that to gain passage you’d have to crawl on your hands and knees—and so dark that midday could seem like late afternoon.

I had spent nearly every Saturday afternoon taking hikes to the tops of mountains ridges on trails I had helped my father blaze on Sunday afternoons, when I’d gather brush his chainsaw blade had burned through, an angry little machine that spat fountains of bright sawdust into the air. So yes. We lived in the mountains. We wouldn’t have far to travel were we to flee into them. We were already here.

+

The day the FBI named Rudolph as a suspect, he did not return the Kull the Conqueror VHS tape he’d rented from his local video store. He didn’t lock his trailer or turn off his TV. Instead, he purchased eleven plus dollars of food from Burger King and disappeared.

The FBI descended full force on my hometown, converting an abandoned sock warehouse into their official headquarters. I’d heard reports from my father about black helicopters flying over the town day and night, searching for any signs of Rudolph, who the feds believed had fled into the surrounding wilderness, a place with which he was much more familiar than those who were searching for him, who would prove to be confounded by the jungle-dense foliage of those rugged mountains, which also happened to be home to over five hundred caves.

According to a local sheriff’s deputy, the FBI were simply inept. These were not woodsmen; these were men with law or accounting degrees who spent their days behind desks in air-conditioned buildings. Not only that, but the trail was cold by the time they started; CNN had announced that Rudolph was a suspect, which meant that once the FBI arrived at the scene, the man would’ve had several hours’ time to weave his way through the woods to the mouth of some secret cave nobody else had occupied for centuries. And whatever trail Rudolph left as he fled had not been unique, at least not bootprint-wise: Rudolph’s boot (Danner insulating hunting boots with a distinctive Kletterlift sole pattern) were one of the most common makes in the country, thus not necessarily differentiating him from other hikers who were, in fact, not under suspicion of blowing people up.

Allegedly, the daily FBI searches didn’t start until 9 and ended promptly at 5, as if the Nantahala National Forest was a workplace the feds were checking into and out of. Agents stuck mostly to well-worn paths that wound through woods so tangled you might not notice a man standing perfectly still only ten feet away. Some of these agents, outfitted in Kevlar vests and toting automatic rifles, didn’t know what a “spring” was, or even “gravity water”; that same local sheriff’s deputy had heard with his own ears one of the agents wonder aloud where people up here in the mountains got their drinking water. One of agents supposedly accepted a necklace made from the twisted vines of poison oak. Another had his curiosity quickly sated after he’d picked up a hornet’s nest, imagining it to be a large cocoon, and was subsequently stung so many times he had to be airlifted to a hospital. One guy, surprised by a deer, opened up on it with a semi-automatic, mutilating it beyond recognition. Others shot at people’s dogs. It was easy to imagine that, as the deputy claimed, the FBI had not exactly endeared themselves to the local citizenry.

+

As someone who’d been dreaming of manhunts—and dreading my own future role as a fugitive—the idea of Rudolph eluding both federal and state law enforcement was compelling. However fucked up Rudolph was on the inside, there were parts of him I admired: his ability to live off the land, and to outwit the supposedly superior investigative forces that had been assembled to catch him. I even could sort of understand—Rudolph’s notions about white supremacy and the evils of abortion and homosexuals aside—why some people in my hometown had been rooting for him, some of whom, as good and upstanding Christians wouldn’t have necessarily endorsed Rudolph’s methods, but would’ve surely sympathized with many of his beliefs, like, “people should marry within their own race” and “abortion stops a beating heart.”

Had Rudolph any access to newspapers, which, knowing now that he’d survived in part by scavenging local restaurant and grocery store dumpsters for food, and that he may have come across a headline or two, he probably would’ve read about the cheers of his onetime peers and thought them ironic. Like me, Rudolph had always considered himself an outsider. Like me, he’d made few friends in the mountain community where he’d grown up. Like me, he’d served as a member of a local sports team. But unlike me—and this seemed significant—he was good at what I’d grown up believing I would someday have to do: take flight deep into the mountains, and survive.

+

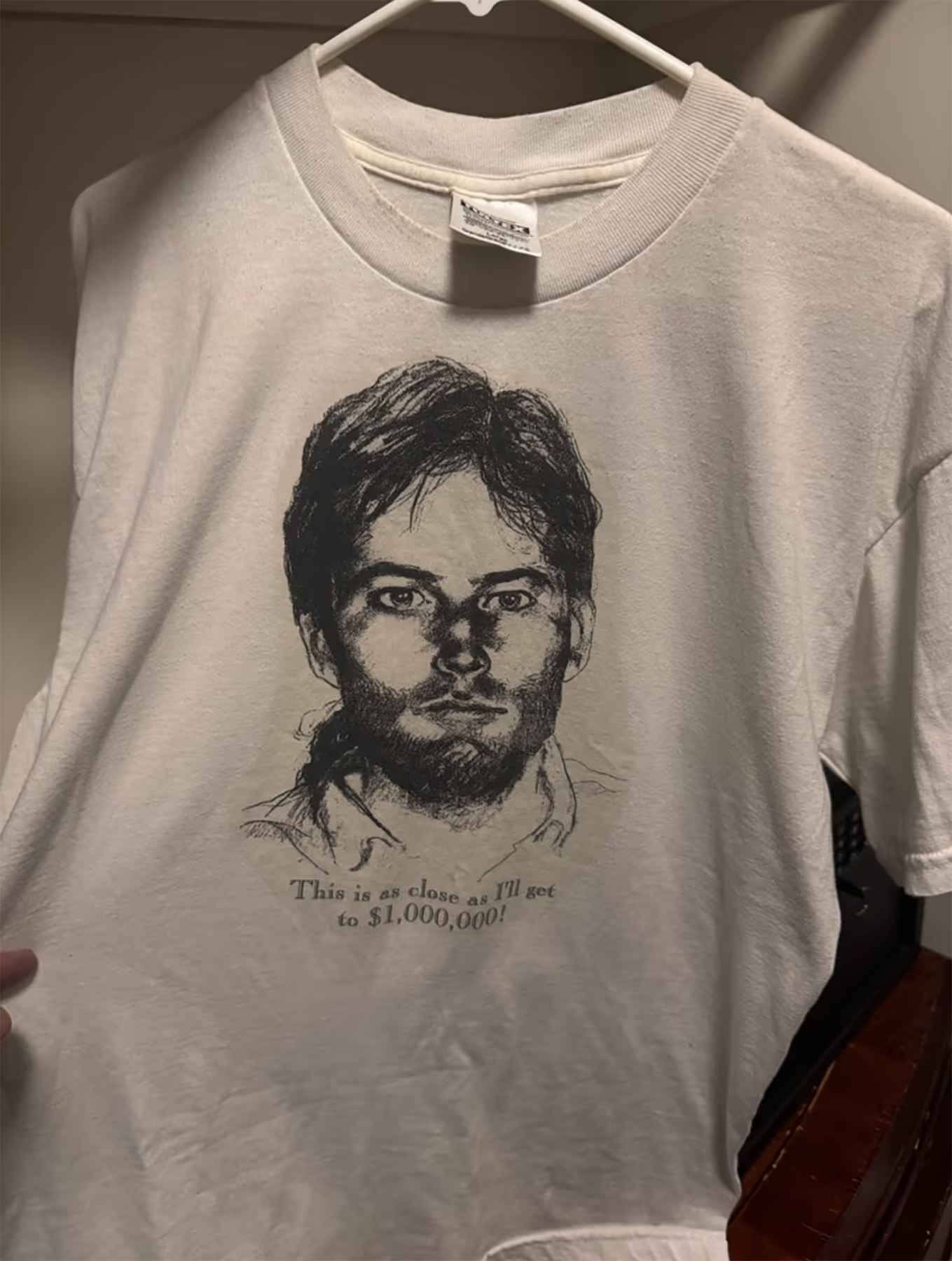

At the height of the manhunt, convenience store signs rearranged the letters of sign boards advertising cigarettes and hot dogs and six packs to read “Run Rudolph Run.” They sold bumper stickers crowning Rudolph “Hide and Seek Champion” and T-shirts with the police sketch of Rudolph’s face saying “This is as close as I’m gonna get to a million,” i.e., the amount of money the government pledged to award anyone who could provide information leading to the fugitive’s capture.

FBI officers outside of Andrews, North Carolina, 1998

“This is as close as I’ll get to $1,000,000” t shirt, 1998, featuring Rudolph’s image

Hundreds of people had submitted reports to law enforcement claiming that they’d seen him. That he’d “waltzed into a store… bought a slice of pizza, three quarts of beer and a phone card, and smelled so bad the clerk had to hold her nose.” That he’d “made calls from a pay phone at a gas station in the next county” and “registered at a local motel.” A bear hunter northwest of Asheville swore he ran into him in the woods. People thought they saw Rudolph making a collect call outside a Houston Walmart, seeking shelter in a lean-to on the Appalachian Trail, and lounging on a Mexican beach. One of my father’s patients claimed that he had a picture of Rudolph—that he’d showed up at a town meeting, and that he was the prettiest girl there.

The more I thought about these alleged sightings, the more interested I became in the mythos of Rudolph’s disappearance. How, as the Washington Post reported, Rudolph was “everywhere and nowhere.” At first, I thought I might just write a fake collection of these so-called “sightings” and call it something like FALSE READINGS.

But then, in the spring of 2002, four years into the manhunt, I rented a car—a red convertible Mustang, which was the smallest and cheapest car the rental place had left—and drove the 514.7 miles from the Midwestern city where I lived to the southern Appalachian town where I’d grown up.

Nantahala Lake, as painted by “D. Pullium,” on the wall of my father’s dental office—the region where Rudolph grew up, minutes away from Andrews, North Carolina.

I was there to do some research—to interview citizens of my hometown. I liked this idea; the idea of research gave me a sense of purpose. I was a writer—an artist, even—with an idea. I just needed to return to the world in which it would take place, and gather information, and write.

I spent a day browsing back issues of the town paper, snapped digital photos of whatever caught my interest: a letter from a local warning his fellow citizens that the passage of a law permitting local eateries to offer “liquor by the drink” meant that the town was poised to become the next Sodom & Gomorrah; a review of a book by a local writer that collected anecdotes about angels and the ways they’d come to the aid of various people, including the driver of an ox cart during a snowstorm and another who had healed a woman of cancer; an article about how a local man, one who’d led FBI agents to the area’s 500 plus caves, spent six hours in a tree, until his pager went off and the bear who had been waiting for him to descend ambled away.

One day, I drove half an hour up into the mountains, to talk to a guy and his wife whose house had been broken into during the manhunt, while they were on their yearly trip to Montana, and how the FBI confiscated all kinds of random objects from their home—even toothbrushes and toothpaste—then returned them in plastic numbered bags, which the guy and his wife presented to me as evidence of invasion of their privacy, and how wherever the guy went, it seemed there was someone who wanted to talk to him about Rudolph, just random folks he had to assume were agents in disguise.

+

I met with the new owners of Rudolph’s house, who showed me eerie home video footage from their first tour—Rudolph himself appearing on camera, guiding them into a room lined with reflective material, likely his marijuana grow space. His former principal described a middle-schooler who was intelligent but disconnected: quiet, friendless, a confirmed loner who once vanished into snowy woods wearing only a poncho, emerging two days later in the same clothes, unfazed. I spoke with a man who’d been jailed for aiming a laser at a helicopter during the manhunt for whoever had fired shots at FBI headquarters. Then I visited Better Way, a health food store run by George Nordmann, whose house Rudolph had broken into to help himself to supplies and who had left five hundred-dollar bills left on Nordmann’s kitchen counter. The FBI suspected collusion, bringing a media frenzy that prompted Nordmann to paper his windows with vitamin advertisements. Inside, dust coated the shelves crowded with Virgin Mary icons, cassette tapes, and religious pamphlets. One sign declared “Shroud of Turin is NOT a fake,” while another warned, “If you smoke in here I’ll hang you by your toenails and pummel you with an organic carrot.”

I interviewed Jasper—a gaunt man with a magnificent pompadour and handlebar mustache—who greeted me wearing a “BAHAMA PAPA” t-shirt. As a child, he’d witnessed a man’s heart “blowed” out his back. Later, before finding Jesus, he nearly killed the man who beat his children. Jasper himself had nearly died, his body permanently blasted “full of lead” courtesy of his brother Ed, who’d shot him point-blank with a double-barreled shotgun out of pure meanness. Years later, when Jasper finally asked why, Ed merely replied, “So that’s why you hate me, because I shot you.” Jasper countered, “Ed, I don’t hate you, I just like to know why.” Ed never answered, never apologized. Instead, every hunting season, Ed deliberately wore Jasper’s blood-stained, bullet-riddled coat from that night—a gesture Jasper equated to “a man going and killin’ a deer and hanging the trophy of the head on the wall.”

Jasper spun wild theories about Rudolph—claimed the fugitive had mob connections (how else could he have survived?), had undergone facial reconstruction, and was probably lounging in the Bahamas. He insisted he’d spotted Rudolph in Bryson City while helping a woman move. Though he felt sorry for bombing victims, he exempted abortion providers from his sympathy because “the bible says you should not kill.” Mid-conspiracy theory, a knock interrupted us. Jasper ushered visitors into another room where, glancing in, I caught him counting pills in what was clearly a transaction he preferred I didn’t witness.

+

My extensive research ultimately led nowhere—at least not where I’d intended. Instead of crafting the definitive account of Eric Robert Rudolph or the people caught in his orbit, I wrote a novel featuring a thinly-veiled version of myself: Clark, an aspiring writer who discovers he’s missing a graduation requirement, abandons college, and discovers his Boston girlfriend’s infidelity. While drowning his sorrows at a bar, he sees news coverage of the manhunt in his hometown. When he mentions to the bartender, “that’s where I’m from,” the man responds, “no shit” and “that’s funny, dude, because you kinda look like him.”

This chance resemblance sparks Clark’s mission—returning home to write about the manhunt. He informs his bewildered parents he’ll be camping in a cave to “get inside the fugitive’s head.” His mother even visits to photograph him in his makeshift wilderness office, finding it both admirable and absurd. But Clark discovers he can only write about how the fugitive mirrors his own spiritual exile—his estrangement from the religious community that raised him to expect his own future as a hunted man. In a twist of mistaken identity, Clark is captured by a bounty hunter with sinister intentions. During their struggle, the vehicle crashes, killing the bounty hunter. Clark escapes but becomes lost in the wilderness he once thought he knew.

The novel alternates perspectives between Clark and his dentist father, who discovers his son’s abandoned cave and begins a desperate search. The story concludes with Clark being shot by someone who mistakes him for an intruder, ending with his parents falling asleep “where they would dream fantastic and terrible dreams about their son, their minds giving him life, their dreams finding ways for him to get back home.”

I submitted the manuscript to my agent days after my son’s birth. Her tearful response to the final page convinced me I’d created something meaningful. I could, I felt, die happy. This was it—the novel that would transform everything. The book that would justify all those months of research, all those interviews with conspiracy theorists and broken-hearted store owners. The story that would pay for diapers and daycare and eventually college tuition.

Days passed. Then weeks. My agent sent updates: “Editor X is still reading.” “Editor Y wants to take it to acquisitions.” “Editor Z loves the writing but isn't sure about the market.” I began to recognize the rhythm of publishing—the long silences punctuated by brief, carefully worded emails that managed to sound both encouraging and ominous.

The first official rejection praised the writing; however, the publisher wasn’t sure how to “position it in the marketplace.” The second came days later: “The committee loved the prose style but felt the narrative was too interior for our list.” Others followed, recycling the same key words and phrases: “unfortunately,” “difficult decision,” “not quite right for us.”

Months turned into seasons. My son learned to roll over, then sit up, then crawl, while my novel collected polite rejections like a magnet draws metal shavings. “Please send us Vollmer's next work,” the editors often wrote, which felt like being told you're perfectly qualified for a job that, despite having been advertised, no longer exists. At least one editor took the novel to a board meeting, where, I learned afterward, “the bean counters” simply said they didn't think acquisition would be worth it. The bean counters—as if my months in mountain caves and health food stores, my conversations with men full of buckshot and conspiracy theories, could be reduced to columns of numbers that didn't add up.

I began to understand something about the distance between the story you’re telling and the one the world wants to hear. I had set out to write about a fugitive, but I’d really only written about myself—about feeling like an exile from my own community, about the strange comfort of imagining yourself as hunted rather than simply ignored. Maybe that’s why it failed to sell. Who wants to read about a fake fugitive when there was a real one still out there, still free, still beating the FBI at their own game?

The rejections grew kinder but no less final. “This is clearly the work of a talented writer," one editor wrote, “but we're looking for something with broader commercial appeal.” Another: “Vollmer has a unique voice, but the subject matter feels too niche for our current needs.”

By winter, I had stopped checking my email obsessively. By spring, I had stopped thinking about the advance that would never come, the reviews that would never be written, the tenure-track job that seemed to recede further with each “we regret to say.” I stopped re-reading it obsessively and applying micro-revisions. Maybe, I hoped, the act of writing it had been enough, that the research itself had been valuable, that some stories are worth telling even if no one wants to buy them.

And so I moved on. Or tried to.

The following spring, my wife and son and I were visiting my parents when my dad got a call from one of his employees: “They’ve caught Rudolph.” A cop, a rookie, on his nightly patrol, had found the fugitive rummaging through a dumpster behind the Piggly Wiggly in nearby Murphy. Turned out he’d had a campsite on a ridge above the high school. He’d been a stone’s throw away the whole time. The next day, my dad and I drove to the county courthouse. There were news trucks, cameramen and reports, policemen, and hordes of local spectators milling about. My dad approached Jack Thompson, who’d served as the county sheriff during the manhunt. Thompson had white hair, a sharp nose, leather jacket. He looked like he was hunkering down inside his own body. My father asked him if he’d seen the fugitive. Thompson said he had. Said he looked to be in pretty good shape. Said, “He looks about like that boy there.”

And then he pointed directly at me.

.avif)

.avif)