Sweet Elsewhere #4: Just Missed

On failure and perseverance in literary pursuits, highlighting the importance of the journey and taking heart from encouraging rejections

I don’t know if all writers have a 25-year-old rejection they still like to read. But I do.

And this is its story.

Sometime in early 2000, I submitted a manuscript—how many journals I sent it to, I can’t say. I might’ve kept track once, in a notebook now lost to time. A good number, I’m sure. Back then, once I finished a draft, I tended to send it out like buckshot from a shotgun—especially if I felt confident about the story, which, let’s face it, I usually did, whether the story merited it or not.

(Delusions of grandeur being an essential element of a writer’s future success.)

This one, which I’d given the pleasantly-odd-and-poetic-to-me title, “Untutored, Flung,” centered on a main character who’d failed to connect with his ex-girlfriend, after hearing that her mother had suffered a traumatic head injury in a car accident. Plotwise, not much happens: Clark, the main character, travels to Boston, meets up with a friend who tells him about the accident. Clark eventually calls his ex, who’s listed in the city’s phone book. She answers but declines to see him. The present timeline is braided with flashbacks to their brief, intense romance and the night they lost their respective virginities, at the age of 18, on a beach in the Bahamas. In reality: the phone call really did happen. The losing of the virginities did too. And while it wasn’t much of a story, I remember thinking the language might carry it.

An excerpt:

At Logan airport, Clark flicked coins into a pay phone, dialed Eun-Jin's number, then braced himself. No answer. He headed for the T.

Down in the tunnels, nothing had changed. Clark squeezed a handlebar as the rickety capsule clattered through the dark, remembering the last time he’d seen Eun-Jin—the weekend in late April when an unexpected Nor’easter hit Boston. On Friday night, Clark and Eun-Jin plunged through snowdrifts towards Avalon, where they drank Fuzzy Navels and danced under cascades of lasers. After a few drinks, Eun-Jin wanted to dance alone. Clark rested on a black leather couch with an ice water. Eventually, a Hispanic man with no shirt, bulging pecs and shoulder-length hair approached Eun-Jin, and soon their bodies were grinding together, his thigh between her legs. Clark marched across the dance floor, grabbed Eun-Jin by the wrist and led her outside. Snow fell, thick and heavy and slow. Sweat crystallized in their hair.

“I was just dancing,” Eun-Jin protested, giggling.

“You're wasted,” Clark said, tugging on her black leather coat.

“Stop pulling on me!” she yelled, slapping his hand away.

“Is ‘just dancing’ grinding on some guy's leg? I can't stand to watch it.”

“Then don’t,” she said, shrugging. Clark eyed her neck, glistening with sweat. He wanted desperately to lick it. They hadn't made love in weeks.

The circumstances surrounding this story—when and where I wrote it—are, I think, worthy of describing, if only because it does seem, in retrospect, pretty weird. I was living in South Lancaster, Massachusetts, during the nine months I’d spent away from Kelly, my fiancée. I had moved there to teach English at the now defunct Atlantic Union College, a Seventh-day Adventist institution I’d briefly attended five years before. While I was there, I resided in a two-hundred-year-old colonial with twin sisters and their one-eyed grandmother, who had an apartment on the second floor and emerged infrequently with a basket of clothes she intended to launder. The twins were identical: brunettes, no more than five feet two inches tall. Some people pretended they couldn’t tell the sisters apart, which I found ridiculous. The difference was obvious: one twin wore dark, dramatic makeup; the other wore none. The twins were almost never at home, and when they were there, they tended to eat something very quickly while standing in the kitchen, arguing with each other about clothes they had borrowed from each other and lost.

The twins took little interest in cleaning; crumbs from the loaves of bread they sawed and ate during their kitchen sessions dried into shrapnel, and instead of washing out their cats’ food bowls, they simply set out new ones until they ran out. The twin who wore makeup kept a pile of clothes on the floor of her room—whose door she kept shut for fear someone might see inside—that was nearly as tall as she was. Their mutual best friend was a big, warm-hearted, goatee-wearing, sci-fi-loving dude who curated a website documenting, in exhaustive but vigorous detail, the twenty-five-plus trips he’d taken to Disney World.

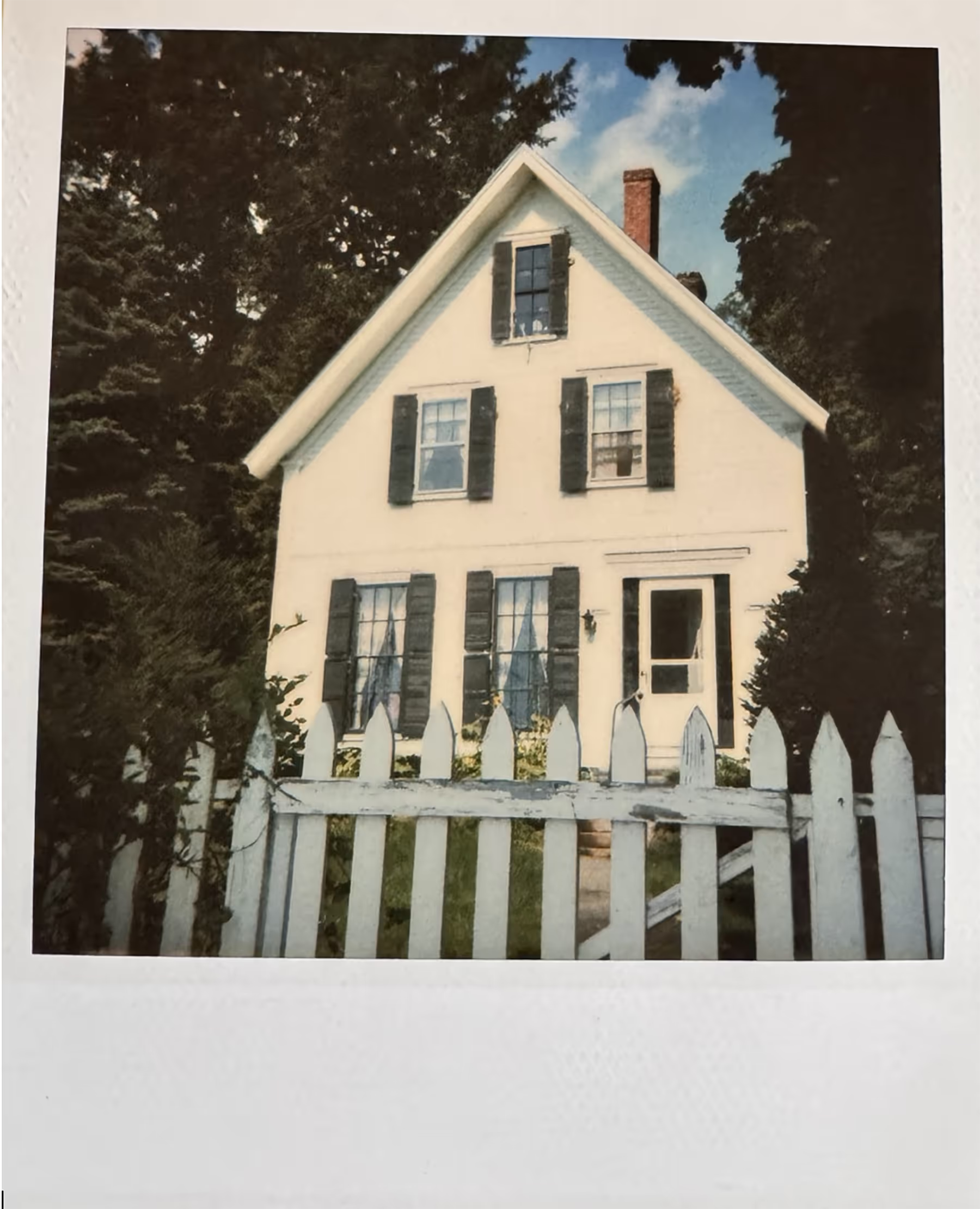

The house on 2 Neck Road, where I lived in the attic for a year.

The house didn’t belong to the twins. It belonged to their parents, who lived and worked at a Seventh-day Adventist medical school in Ohio. Years before, when the twins and I had been classmates in college, the twin who eschewed makeup and I had taken a literature course in the Romantics from her father, who, to my eyes, resembled a diminutive Francis Ford Coppola. I can’t remember much from that class. But I knew, because the twins told me, that when they were children, their father liked to read them Homer at bedtime.

It had only been six years since I’d left Atlantic Union College to transfer to the University of North Carolina, but the college had changed significantly. For one thing, there were hardly any white students. At some point, Caucasians in New England who identified as Seventh-day Adventists—a population which, I assumed, but had no way of proving, was probably shrinking—had decided to go elsewhere. The Atlantic Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists served New York, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, as well as Bermuda, and most of the students in my classes were from inner city Boston, the Bronx, or the Caribbean. Many of them were conservative—and, it seemed, archaically so. I distinctly remember one kid—a tall Jamaican who dressed like a grandpa, in horn-rimmed glasses; a beige, detective-style trench coat; and fedora—who argued with me about whether and to what extent gender was socially constructed. I’d asked him to imagine that he’d grown up in a culture where all the men wore skirts. Could he imagine wearing a skirt? He could not—and would not. During another related discussion that devolved into a series of outbursts about the evils of homosexuality, I asked the men to imagine a future in which they raised a kid who turned out to be gay. One guy said he’d beat it out of him. Earl, a black kid with thick square glasses, held up two fists to pantomime the repeating action of a machine gun, and grinned.

My students’ skill levels varied wildly, especially in my freshman class: one kid literally could not write a complete—much less coherent—sentence. I naively assigned my second term freshmen Flannery O’Connor; most of them might as well have been reading about Martians. Every once in a while, a sunbeam would pierce through the murk; I still remember reading a paper by a young, big-cheeked Puerto Rican girl who had believed her relatives when they told her that the streets of New York City were paved with gold, but once she got there, every corner was piled with rotting, fly-haloed garbage.

The big room at the top of the stairs in the White House served as my office. I shared it with Dave Knott, the professor who’d presided over the first real literature course I’d taken in college: American Literature. I didn’t see much of Mr. Knott, who was now semi-retired, but I was always glad when I did. He’d appear infrequently, his face ruddy, his white hair combed in grooved rows, wearing a light windbreaker, to meet with a student or to search for something. “Don’t let me bother you,” he’d say. “I’m just looking for a book.” Then he’d kneel before one of the towering bookcases, browsing quietly, until I asked him some question I knew he’d know the answer to. I especially liked asking him questions about New England—and often asked him advice about where I could go to take a good hike. Then he’d fall into a rhapsody about Thayer Woods, or the beavers in Wachusett Meadows, or the eerie forest that still held the stone foundations where a town used to be, before it was evacuated and flooded.

I also shared this space, to a certain degree, with Ottilie Stafford—a tall blond woman whose face crinkled into a thousand lines when she smiled; she had to walk through it to get to her own office, a small, bright, many-windowed room on the other side of mine. Dr. Stafford often seemed exhausted by frustrations that year, and rightly so—after years of dedicated, brilliant teaching, the administration had failed her, by refusing to listen to or accommodate all manner of her requests, refusing, often in the smallest ways, to be competent. In several years, Dr. Stafford would be dead, and not long after that, the school would be, too. Her eyes lit up, though, whenever I asked her about Stevens or Frost—or, for that matter, anybody who was anybody in the world of poetry. When I listened to her talking about the poets she’d seen give readings, years ago, at Worcester and Cambridge, I missed the old days, when the department had thrived, when English classes were brimming with smart, inspired students, and when the administration touted the prestige of the department, rather than finding ways of trying to diminish its worth.

It was a lonely year. I was living a thousand miles from the woman I loved. Because the twins often came home late and left early in the morning, I frequently had the whole place to myself. I spent hours wandering, listening to the two-hundred-year-old floors squeak, leafing through piles of old New York Times, lounging on the dusty, shabbily elegant furniture. I read the Letters of Wallace Stevens, James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime, and the 700-page tome of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. I tried to avoid the cats, to whom I was allergic, and who tortured me by napping on my bed pillows or bringing me fresh, wet mouse heads.

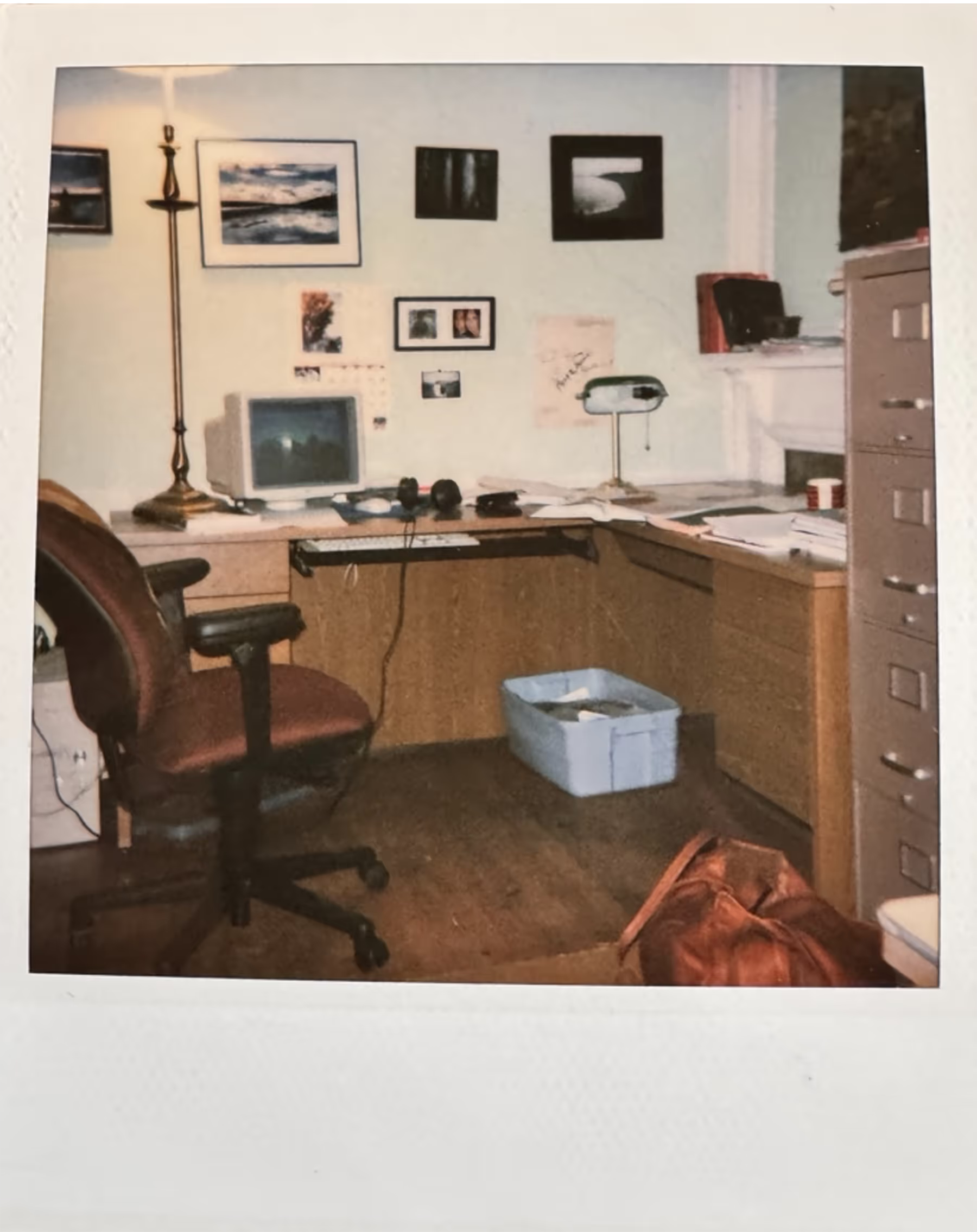

When I wasn’t at the House on Neck Road, or teaching class, or driving aimlessly around the New England countryside, I was in my office in the English department, writing and preparing manuscripts to submit. I spent entire days there, in a giant old building that had once belonged to the Thayer family and was now simply known, by students and faculty, as “the White House.”

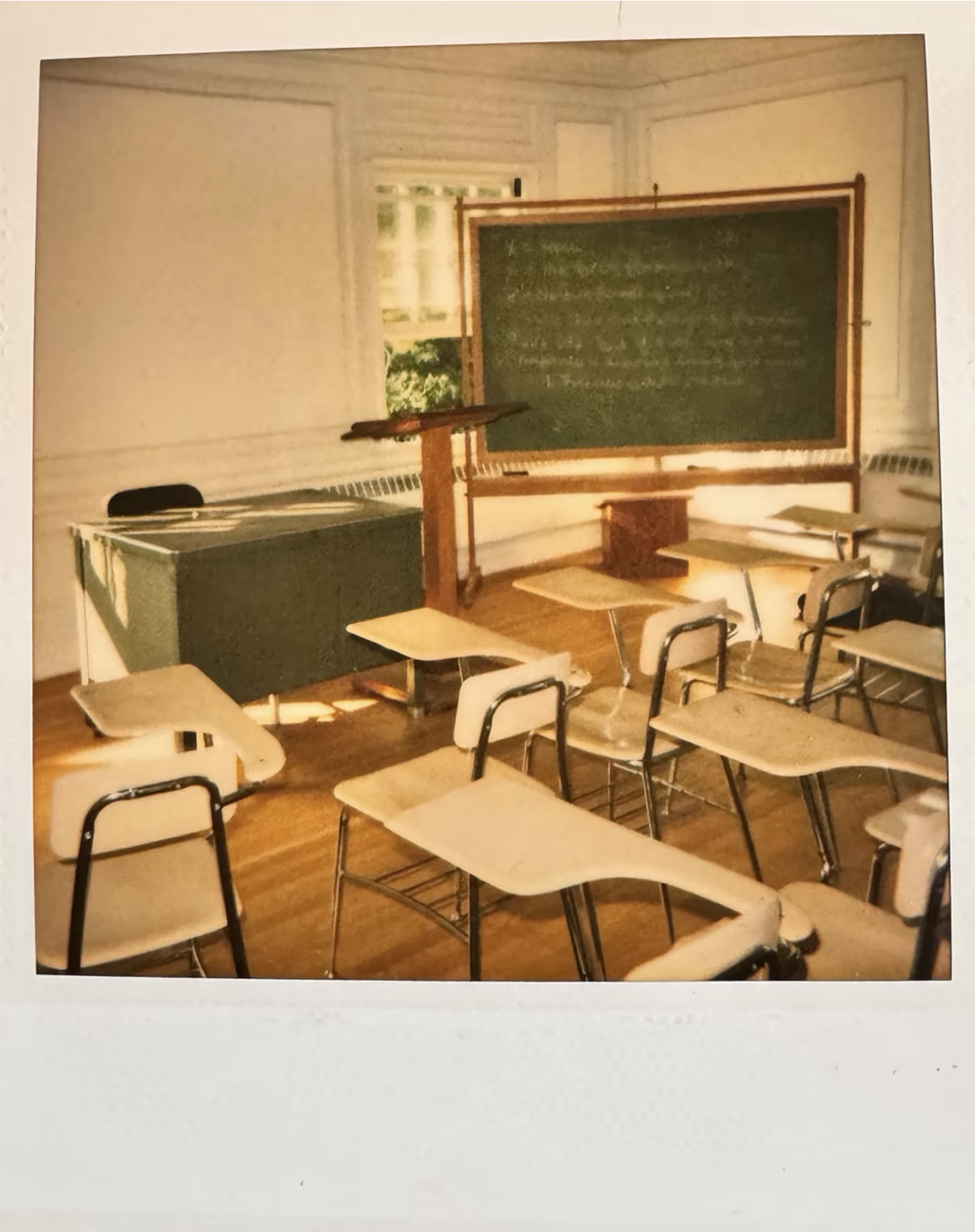

My office, in the White House, at Atlantic Union College, circa 2000.

During the week, I was often the first person to arrive and the last to leave. I haunted the building on weekends. My students dropped their mouths when they saw me on campus proper—they thought perhaps I’d been exiled to the White House and couldn’t escape. Granted, I didn’t have much else to do, but I also loved the idea of having an office. If I got bored, I wandered. I loved the austerity. The emptiness. The smell of old wood and dust and metal and carpet. The crazy wallpaper in the classrooms, the rickety old mobile chalkboards. The heavy door at the front of the building, whose fragile window pane rattled when you shut it too hard.

Classroom, White House, Atlantic Union College.

I wrote a lot in that office. Stories. Comments on papers. Messages to my friends, and to Kelly, who once offered this stunningly heartbreaking—but ultimately teachable—rebuke: Why can’t your stories be more like your email?

I also wrote cover letters. One of which I’d sent, with the aforementioned story, to The Paris Review.

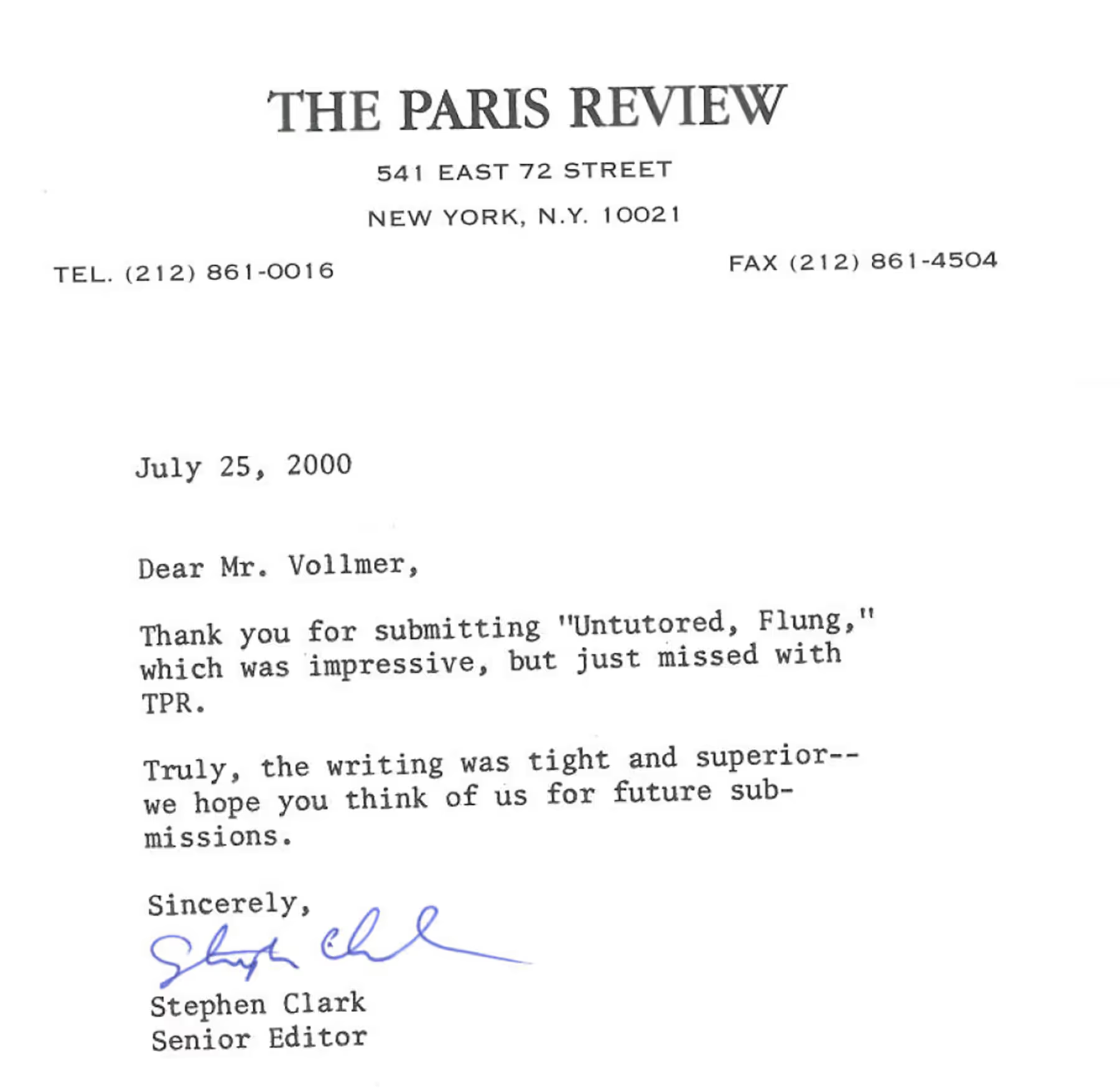

Months passed. The semester ended. I said goodbye to the twins and the cats and the one-eyed grandmother and moved back to North Carolina. Kelly and I married, traveled to Mexico for a honeymoon I spent mostly on the toilet, thanks to Montezuma’s Revenge, and then to Amsterdam and Utrecht, for a conference where she was presenting. We returned to the U.S., moved to Lafayette, Indiana, where Kelly began her PhD. in Rhetoric & Composition, and where I’d been given a position teaching first-year writing. Not long after our move, a letter arrived. I have to assume it bore my own handwriting: a sure sign, at the time, that a rejection for a story I’d submitted to a magazine had been nestled inside. And I was right: there was a rejection inside. But it wasn’t a form slip. It’d been typed on stationery that bore the familiar font of The Paris Review, the date neatly pressed across the top like a raised eyebrow: “July 25, 2000.” And then: “Dear Mr. Vollmer,” followed by “Thank you for submitting ‘Untutored, Flung,’ which was impressive, but just missed with TPR.” The letter had been signed in blue ink by someone named Stephen Clark, Senior Editor of Paris Review.

I re-read the words. “Impressive.” “Just missed.” “Tight and superior.” The note seemed like a prop from the movie of my life. Someone at The Paris Review had not only read my story and enjoyed it, he’d typed kind words onto real paper. And had signed his actual name. I pinned the letter above my desk. I thought of it as talisman. As symbol. And, with that invitation to think of them for “future submissions,” a promise.

Six books, 200 publications, and twenty-five years later, I found the note again and, for the first time since receiving it, wondered what had become of “Stephen Clark, Senior Editor.” His position, even now, seemed like a big deal, a stepping stone to a place I could only imagine as “extravagant” or “legendary.” After all, Brigid Hughes, who’d been Managing Editor at the time, now ran A Public Space. Phillip Gourevich, who’d also been a senior editor, had become a staff writer for The New Yorker. Designer Charlotte Strick had gone on to design covers of famous books—ever hear of 2666 by Roberto Bolaño? Freedom by Jonathan Franzen? Phillip Roth’s entire catalog, redesigned?—and opened her own firm. But Stephen Clark? He seemed to have vanished. A Google search summoned a story—“The King Will Ride”—that had appeared in the Spring 1999 issue of The Paris Review, along with hits for digital issues of the magazine during his time on the masthead. But I couldn’t find anything else. Had he, like Editor George Plimpton, Poetry Editor Charles Simic, and Advisory Editors Donald Hall, Peter Matthiessen, and William Styron shuffled off this mortal coil?

Eventually, I entered Clark’s name into ChatGPT. I typed in what little I knew. Within seconds, it gave me what I hadn’t yet been able to find: a link to his website. The trick, it turned out, was to search for Steve Clark—not Stephen.

I sent Clark—only now, while writing this essay, did it strike me that his last name matched the first name of the main character of the story he had kindly rejected long ago—an email with the subject line “I’m Writing an Essay on Rejections and Yours Was the One that Kept Me Going.” He replied. And soon we were talking on the phone.

Clark—generous and funny and warm—reminisced about The Paris Review in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when he played tennis and got drunk every Friday with George Plimpton, the magazine’s famously charismatic, patrician editor. Clark spoke fondly of how, not long after he’d been hired as an intern, Plimpton had whisked the staff off to Tortola, to the home of Remar Sutton—author, consumer advocate, and former advertising executive—sweeping them into the kind of literary fever dream that only a man who once took five snaps with the Detroit Lions could orchestrate. Clark had boarded a plane with a motley crew of writers, friends, and hangers-on, including Elizabeth Wurtzel, the sharp-tongued author of Prozac Nation, and filmmaker Todd Komarnicki. When they landed, a party bus picked them up. There were meetings with the mayor. Mushroom teas. Midnight swims in phosphorescent Caribbean waters. The whole thing, apparently, had been equal parts literary salon, beach bacchanal, and surrealist summer camp.

Back then, The Paris Review relied on unpaid readers—mostly MFA students and moonlighting poets—who volunteered once or twice a week in the first floor of Plimpton’s 4,700-square-foot duplex at 541 E. 72nd Street. Nearly every room had a view of the East River. It was there, amid bookshelves and dust motes and scattered manuscripts, that the staff sorted through the “slush pile”—the unsolicited submissions that made up the vast majority of the magazine’s 16,000 annual entries.

Readers placed each story in one of several piles. An “A slip” meant a flat rejection—thanks but no thanks. A “B slip” carried a slightly warmer farewell: a form note that said “please think of us for further submissions.” Occasionally, if a piece struck a particular nerve, a reader might write a personal note—encouragement, maybe even a request to see more. But the real honor, the holy grail, was to be placed “in the bin.” The bin was a curated stack of contenders. Every story in the bin got read by the rest of the staff: interns, editors, whoever was in the office that week. Only after it had made its way through that small, hand-to-hand gauntlet would a story land on George Plimpton’s desk. He made every final call.

“Someone spotted you in the slush,” Clark told me. “And put you in the bin. That must’ve been where I found you.”

Three years and two months after Clark mailed me his handwritten rejection, Plimpton died in his sleep. Clark left the Review not long after, pivoting away from the New York literary scene to become a filmmaker—a director who once made a movie about Jeremy Irons having a meltdown on a road trip with his son. He painted solo shows that looked like jazz sounds. And in 2024, he published a story collection, City Swimmers & Other Stories, that Kirkus called “entertaining” and “thoughtful.”

According to Clark, The Paris Review never made much money. But Plimpton—a natural raconteur who never told the same story twice—could light up at the smallest victories. Selling even a single ad page was cause for celebration. One time, he managed to throw a party on a tiny island off 52nd Street that had once housed an insane asylum. Somehow he made a little money off it. Then the rented piano was left outside in the rain. “That party,” someone joked, “caused the most divorces in New York.”

To think that something I had written—typed on a Dell desktop in a cold office in Massachusetts, in a year when I was lonely and newly married and homesick for something I couldn’t name—had managed to penetrate that world, that mythology, that duplex of ghosts and geniuses and eccentric, brilliant misfits… it stunned me. I had no idea whether George Plimpton had read “Untutored, Flung,” and didn’t ask Clark whether he thought he might have.

But I kept the letter. Kept re-reading it. Kept writing. Kept editing—relentlessly, furiously, inspired by that “just missed” and the invitation to think of them for “future submissions.” As much dreaming as that rejection slip inspired, however, I couldn’t have predicted that, in less than six months, my second published story would be accepted by The Paris Review. Or that, the following summer—not long before the planes hit the towers, and the world forever changed—I’d be at a revel in the catacombs beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, where George Plimpton himself would introduce me to one of my literary heroes. Back then, all I needed was Clark’s note: a crisp rectangle of stationery that had passed through the hands of an editor who’d liked what I’d written enough to type up a few kind lines: sentences I reread, over and over, like sheet music for a hit I had yet to write, but knew, someday, I would.

George Plimpton in The Paris Review office. (Via The Paris Review.)

.avif)

.avif)