Sweet Elsewhere #5: And You, You Ridiculous People, You Expect Me to Help You

Matthew Vollmer's fifth essay in the series exploring the inevitability of failure in literary pursuits and the remaking of the creative self with every new draft

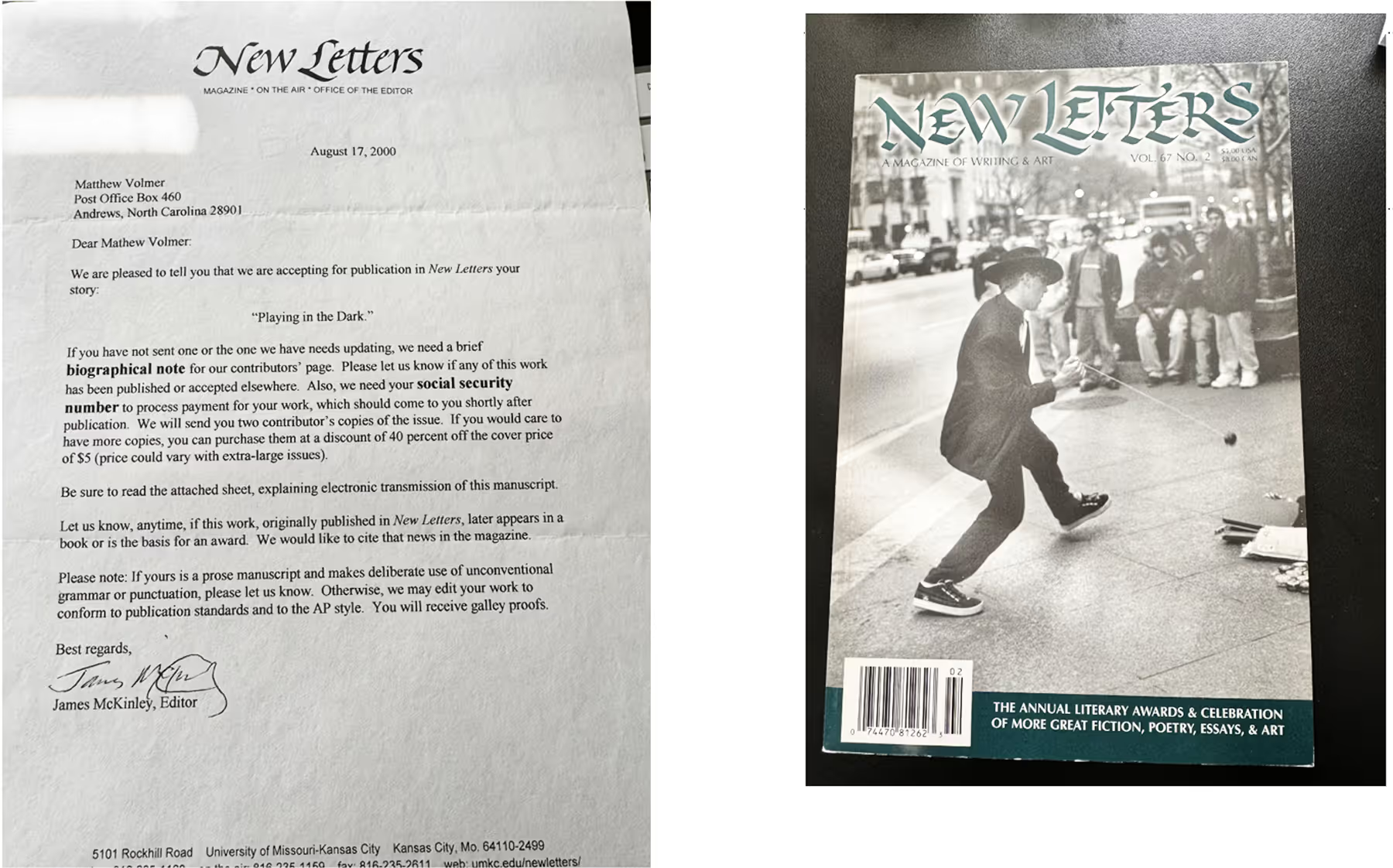

In August of 2000, years after regularly submitting work to literary magazines—and collecting enough rejection slips to wallpaper a small bathroom—I received my first acceptance. The letter was from James McKinley, editor of New Letters, a magazine produced by the University of Missouri at Kansas City. McKinley was pleased to inform me that the magazine was accepting my story, “Playing in the Dark,” and that they needed a brief biographical note and my social security number, to process payment. I would also receive two contributor’s copies of the magazine and the chance to purchase additional copies at 40 percent off the cover price.

I was ecstatic. The day I had been waiting for had finally arrived. All that work—the drafting and re-drafting and sanding and refining; those trips to the post office and stationery stores to purchase manilla envelopes; all those S.A.S.E.s I’d prepared with care, as vehicles to transport my future rejections—had finally paid off. The start of a prolific career was now no doubt in the process of unfurling.

My first response?

Panic.

I’d submitted the story months before and had since substantially revised it. What if James McKinley and his staff didn’t approve of the revisions? What if they insisted upon the original title, even though I had now changed it to “Watchman, Tell Us of the Night,” after encountering a hymn of the same name? These were, of course, the apprehensions of a newbie: as soon as I contacted McKinley—did I email him? call him on our landline?—and breathlessly relayed my concerns, he said something like, “Don’t worry. We want our writers to publish the material they want to, in the manner they want to see it.”

“Our” writers, I thought. Cool.

It was, then, official: I was a writer. Soon I would have proof: two contributor’s copies of the magazine, with a black and white photo on its cover of a young man in a black suit and hat, slinging a yo-yo. A copy would arrive at my father’s dental office and his staff, studying this image closely, would convince themselves—albeit inaccurately—that the man in the photograph was me.

One cold fall day in West Lafayette, Indiana—it was a day of the week I didn’t have to teach—I went to get a haircut and pay a visit to Von’s, a bookstore at the edge of Purdue’s campus. My wife Kelly was in the first year of her PhD program, and I was teaching four composition classes a semester, with 24 kids in each, which meant that on paper due dates I normally received upwards of ninety-some 3-4 page papers: that, in addition to teaching and reading in-class work and attempting to write my own stuff and keep up, to some extent, with what was happening in the literary world, visiting the library to check out journals, and volunteering to read submissions for the university’s own nationally distributed magazine, and having conversations with my office mate, who, in addition to teaching his own sections of composition and attempting to finish a dissertation on a lesser-known poet who had committed suicide, was an ROTC guy, who, on the weekends, served his country by guarding marijuana patches, an occupation he found ironic, in part because he enjoyed firing up a doobie himself now and again.

On the day in question, I’d been browsing the “Literary Theory” section of the bookstore, having recently become interested in the French theorist Maurice Blanchot, a writer with whom, at the time, I imagined I was on the verge of understanding. I heard someone call my name. I looked up. Kelly was standing beside me in the aisle, in slippers and pajamas and a jacket, without makeup. This alone was startling. Though she was neither vain nor attention-seeking, Kelly never left the house without “getting ready.”

She grabbed me by the shoulders.

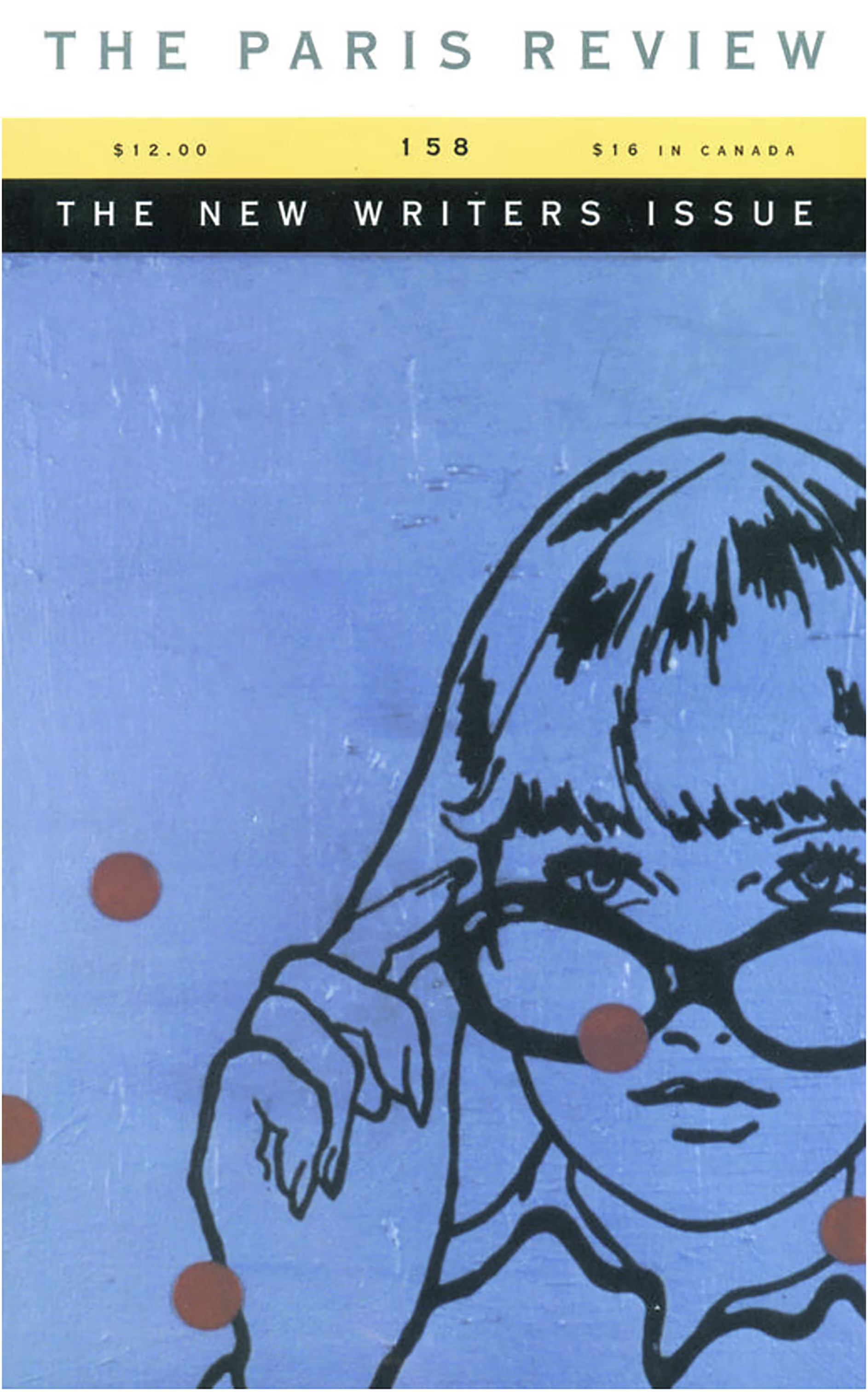

“Someone from The Paris Review just called! They want to publish your story!”

I froze. Brain short-circuited. The sense of elation was immediate and profound. I couldn’t have been more surprised than if she’d walloped me in the head with a two by four.

A short, meaty guy, wearing the kind of shirt worn by men who work at automotive repair shops, and which had a patch with his name—“Tom”—on it—pushed out his bottom lip and said, “Paris Review. Good magazine.”

Good magazine, indeed.

Kelly and I rushed home. I called the editor, my brain a broken record of worst-case scenarios: What if it wasn’t real? What if there’d been a mix-up? What if they meant to call someone else entirely and I’d just happened to catch a ricochet of luck? Because what else could explain the fact that The Paris Review—a venerated magazine that had rejected me before, a magazine that rejected everybody—wanted something I’d written?

My first thought was: I fucking did it.

What “it” meant, exactly, remained unclear, though it would be right to say that it felt as if I’d been drifting on an open sea and finally found land. I assumed that now I could include The Paris Review into the body of future cover letters and that doing so would, like a magic key, grant me access to other big time or at least average time lit mags, and that furthermore, I might be a regular contributor to the magazine; after all, they’d liked the story enough to feature me as one of handful of “New Writers”; perhaps this qualified me as an artist who was not only emerging, but whose success was now sure.

The Paris Review had not, as I’d feared, made a mistake. They intended to publish my story, “Oh Glorious Land of National Paradise, How Glorious Are Thy Bounties,” a tale about a young man named Harper, a waiter at the Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone National Park, whose BFF Wes got hit by an RV and who bled out in the road, a complication amplified by the fact that Harper happened to have been covertly sleeping with Wes’ girlfriend, Abby. The new issue would be launched at a gala—a revel—in New York City, inside the Brooklyn Bridge, at the Anchorage, a space that would later correctly be described by the writer Cassie Carter on Catholicboy.com as “a catacomb-like space underneath the bridge, on the Brooklyn side,” and which had originally been designed to hold a US mint or treasury.

And so, two months before terrorists flew planes into the Twin Towers, Kelly and I descended upon New York. We stayed in a friend's apartment—a time capsule that seemed untouched since the Kennedy administration, with no visible bedroom until my friend, with theatrical flair, unfolded the couch and announced "voilà!" to reveal our sleeping quarters. At the Brooklyn Bridge, we joined the line of literary pilgrims, eventually meeting Brigid Hughes, who introduced me to Paris Review staff. They floated through the room in their stylish glasses and dapper clothes, young and coolly distant, until George Plimpton appeared—the legendary publisher and Editor-in-Chief, tall and loose-limbed, greeting me with equal parts bemusement and enthusiasm. He swept me into a whirlwind of introductions: Helen Schulman, Rick Moody, Jim Carroll (who assured me he recognized exactly what I was feeling that night), and finally, Denis Johnson. Like every aspiring writer who'd encountered Jesus' Son in their twenties, I had pored over his work with monastic devotion. Later that night, after each writer had read—Johnson had read “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” a first-person story that, with its final swerve into direct address: “and you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you,” had the effect of blowing my mind out like a candle[1]—Plimpton introduced me to Johnson. Above us, lasers swung through the dark. Black lights flickered. Johnson gestured to this display and said something about needing to “get out of here” and that maybe he’d just snag a slice of pizza. Like the kind of the overly friendly moron I can be, I elbowed him and said, “What, having a flashback?” Johnson didn’t reply.

Despite the fact that I’d met and promptly insulted my literary hero, I now had a copy of the issue in which my story appeared. I’d even seen the issue out “in the wild,” where a young man had been reading on a stoop in Greenwich Village. I’d visited a professional recording studio where I read an excerpt of the story into a fancy microphone for Salon.com. And I’d had lunch at a Manhattan café with a young aspiring literary agent, who’d oh-so-cavalierly whipped out her agency’s credit card to pay for our meal, thus prompting me to indulge the notion that like maybe I could start looking forward to meetings like this in fancy New York City restaurants.

[1] Shout-out to Angela Carter, who uses this simile in “The Loves of Lady Purple”

Cover of The Paris Review, #158, The New Writers Issue, Summer 2001

The aspiring agent worked an administrative assistant for Darhansoff & Verrill, a coupling of names that struck me as enigmatically prestigious, but she was in the process of “building her list.” She was cool and confident, and when she offered to let her send out some of my stories, I thought, this is it. The part where the door stays open. This part where I become a literary person who has a literary person handling their literary affairs.

And Alexis—that was her name—did place a few stories in good magazines. Magazines with reputations, publications with readerships. And for that, I was genuinely grateful. She was a kind and gracious reader. Until, one summer day in 2002, I got a phone call that broke whatever spell I was still under.

She was leaving publishing.

Not for another agency.

Not for another coast.

I was flabbergasted. I wanted to know why. Alexis explained: it was time, she’d decided, to pursue her lifelong dream; she wanted—despite her parents’ wishes—to become a cosmetologist.

I did see George Plimpton one other time. In the days and weeks following the publishing of the New Writers Issue (#158), the news of my Paris Review acceptance had spread, and snagged on a few antennae of local media: I'd been interviewed by a guy named Chuck Culver on public radio and invited to a party in a suburb of Indianapolis, thrown by a man who'd made all his money in heating and cooling—a retiree who happened to be a benefactor of the local art scene, as well as an armchair Civil War historian.

I attended the party alone. A Black man in a tuxedo and white gloves—perhaps a butler, perhaps not—opened the door after I knocked. Another woman, also Black, ferried a sliver platter of hors d'oeuvres between guests, which included a man who edited a men’s magazine and a woman who did news graphics for a local station. No one I’d ever met before. No one I’d ever see again.

We had convened not for one another but for our guest of honor: George Plimpton. He was slated to deliver a keynote of some kind the next day. Plimpton arrived at the party with all the aplomb and brashness you would expect. His face like a caricature of itself. Towering, heavy-lidded, beaming like a benevolent ghost of literature’s high society. He seemed taller than 6'4: a spry, handsome beanpole of a man who shook hands enthusiastically and—after I'd reminded him of who I was—erupted with, "Oh yes! The young man with the geyser story! You must send me something else!" and then went on to lovingly insult the Confederate statues of Indianapolis.

Of course, by that time, I had sent Plimpton stories, each of which were kindly but summarily rejected. Why they wouldn't want "The Boogeyman's Twinlust," which featured a sad-sack of a character who discovers that his nose, when picked, has become capable of delivering miniature letters of the alphabet that spell out messages, Ouija-board style, I can't explain.

Caterers had assembled some kind of buffet, and I found myself standing in line. Now's your chance, I thought. Impress Plimpton with something. Make him laugh. Remember you.

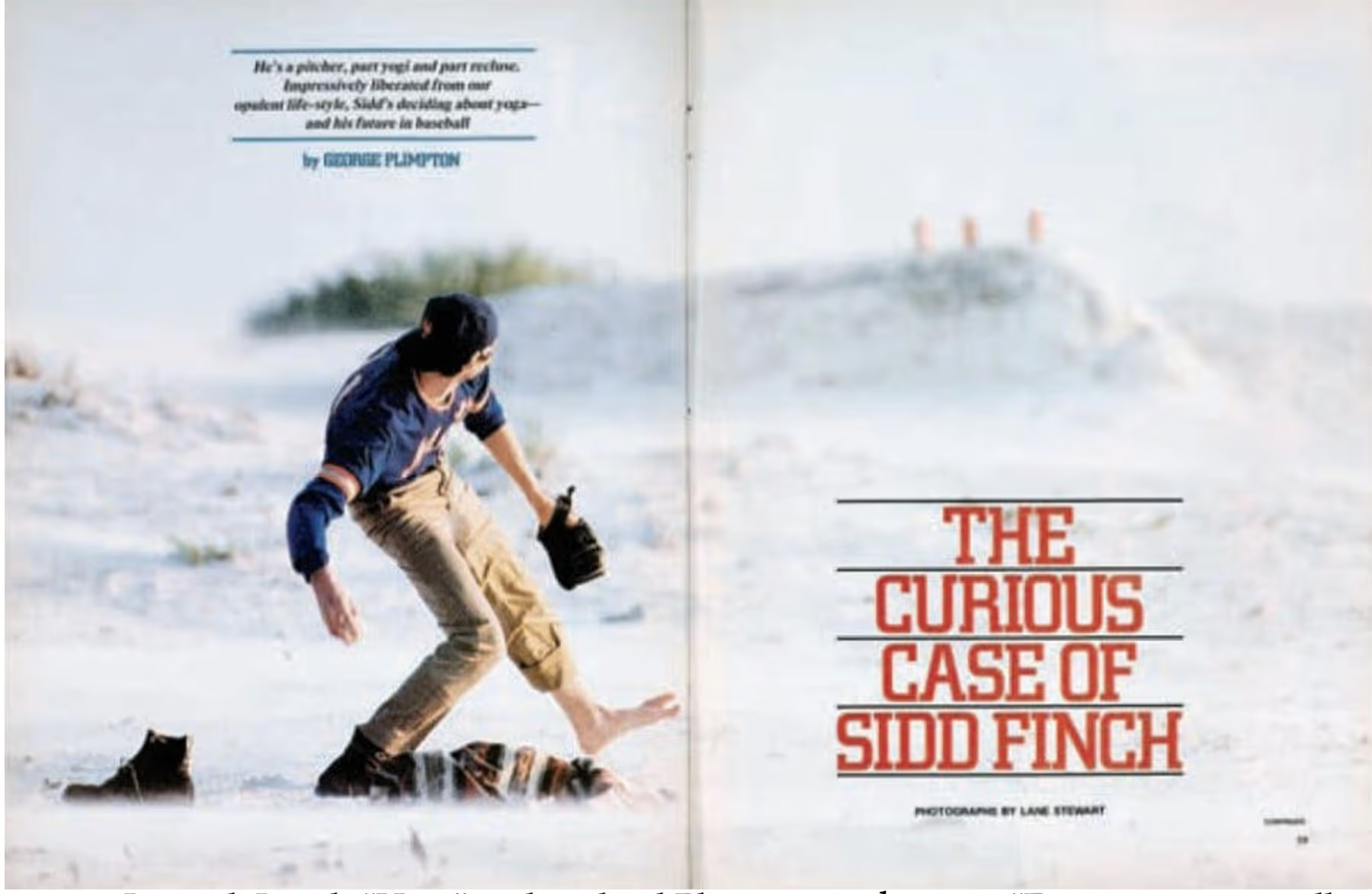

Thinking back on it now, I should have told him about the first time I met him: in the pages of Sports Illustrated, the week of April 1, 1985. I was eleven years old. Sitting on the floor of my bedroom inside a house at the bottom of a mountain, at the end of a dirt road, on a hill above two streams. It was there, among my Legos and G. I. Joe Men and MAD magazines and the photo album where I kept cut outs and newspaper clippings of the Dallas Cowboys, that I had read, with deepening interest, “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch,” an article by Plimpton about a Mets pitcher who’d been raised in an orphanage, lived in Tibet, and could throw a fastball 168 mph. I'd absolutely believed the article, and as a Mets fan—if only because I thought Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden were the two coolest dudes in baseball—I devoured. Also? I believed every word. I became even more delighted, however, once I realized—perhaps in a subsequent issue?—that the entire thing had been a hoax, and that the first sentence of the piece—“He's a pitcher, part yogi and part recluse. Impressively liberated from our opulent life-style, Sidd's deciding about yoga—and his future in baseball”—had served as an impudent clue, as each beginning letter of this first sentence's words spelled out “Happy April Fool's Day.”

Instead, I said, “Hey,” and nudged Plimpton in the arm. “Funny story, actually. Or rather coincidence. One of my former professors at North Carolina State University, guy who teaches literature there, Harvard grad, he said that he actually has your former masseuse in his Poetry class.”

Plimpton spun around, holding an empty plate to his chest. “Masseuse?!” he barked emphatically. “Why I've never had a massage in all my life—not even in a Thai bordello!”

And that was it.

The end of my Paris Review arc.

Except it wasn’t. I kept sending stories. Kept believing, even after each new “Not this one.” I had to. I believed, foolishly or faithfully, that something inside me was still worth transmitting. Even if the message came out in weird little letters. Even if nobody understood it but me.

I haven’t submitted to The Paris Review in a long time. The magazine hasn’t felt the same since Plimpton left. Since the staff moved out of his apartment with those views of the East River. I found a real estate listing online, got a glimpse of expansive sun-splashed rooms, the site of my most beloved acceptance. In the photos, the river looks close enough that you could sit on one of the couches and imagine the entire place might be a ship about to sail off into forever. But first, of course, you’d have to get inside. Which wouldn’t be easy. As of this writing, the apartment is for sale. For 5.25 million dollars.

I think of all the submissions that passed through that apartment—approximately three-quarters of a million between 1953 to 2005—and all those readers, digging through the slush, hoping to find gold. I still remember, with fondness, how long and hard I worked on the story that Plimpton and his staff said yes to: how I revised it by reading every sentence out loud, over and over, finding those just-right rhythms, and finally sending it off with an accompanying cover letter and S.A.S.E., dropping the packet into a mailbox. I like imagining the machines that sorted it, the vehicles that shipped it to the City of Dreams, the mail carrier who delivered to the red door of a building that had once been a tenement and was later renovated into a posh apartment, where a staff member ripped open the envelope, read the contents, passed it around somebody else, who passed it to somebody else, and how, after everyone had given the story a thumbs up, somebody delivered it upstairs, to George. Of course I have no idea what his response was, though I like to think he said, simply, “Fantastic!” Because it was fantastic. But also? Like every success, it was fleeting. I didn’t publish another story in Plimpton’s magazine. And two years later, he died in his sleep—in the fabled apartment.

I tell my students all the time: no matter what you do, the truth is: every time you complete a story or essay or poem, you're back to ground zero. And maybe that's the best and most ridiculous part of all. You keep remaking yourself, word by word, day by day, building a new addition onto the body of work that is yours even as you wonder if anyone will ever read it, care about it, or remember it. Out of those hundreds of thousands of submissions to any literary journal, only a fraction—probably no more than 5%—will ever see publication. The numbers are sobering, the odds absurd. And yet we keep writing, keep submitting, keep believing that the next submission might be the one that lands. Because it might. It’s all part of the unforgivingly grueling process—one that you realize, but only later, is its own sweet reward.

.avif)

.avif)