Behind the Scenes of Alice James Books with Carey Salerno

In this interview with Executive Director of Alice James Books, publisher Carey Salerno explores the intersections of publishing and writing poetry in the world today and for the future ,

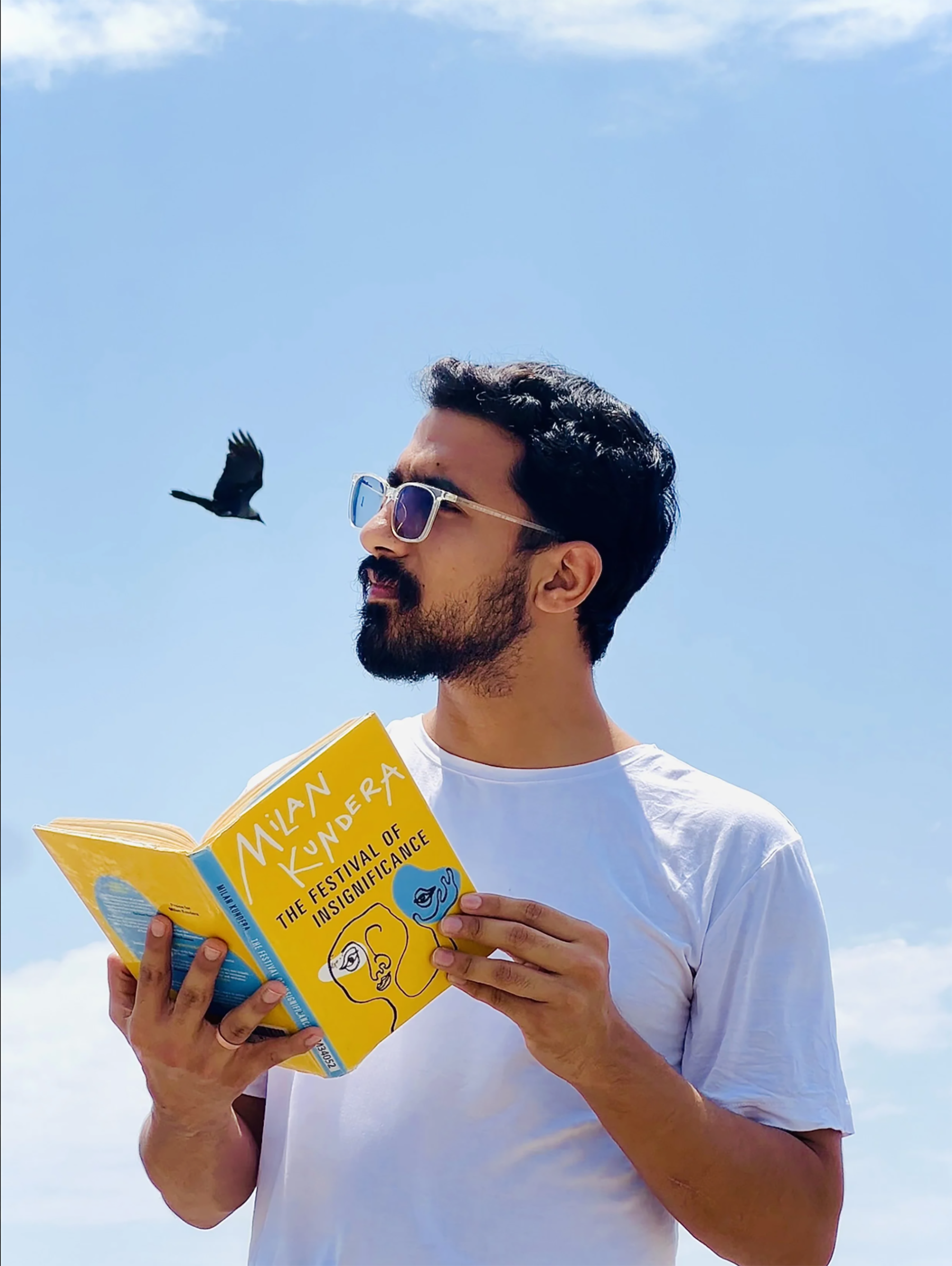

KARAN

What does a typical day in the life of an executive director at Alice James Books look like? Could you walk us through some of your key responsibilities and tasks?

CAREY

I really love this question! It makes me smile, because there really is no typical day for me at AJB even after having been at the press for over fifteen years. Every day is different and usually involves a mix of work in an array of areas. For instance, this morning I was working on answering some final questions an author had about their forthcoming book. We just finished the developmental edit together a few weeks ago, and they were wondering about potentially adding a couple of new poems, a new line edit, and our stance on acknowledging blurbers in the acknowledgments section. So, we were going back and forth on those items. After that, I wrote a grant application. Then, I had an interview with a student at a local university, and after that, it was budget meeting time as we just rounded out fiscal year 2024.

While it can seem unpredictable, I can say it’s never boring. The work keeps me flexible, and I feel most engaged and energized when I need to stay nimble.

As the ExDi & Publisher, I’m responsible for the creative and operational visions for the press. This means that I oversee the curation of AJB’s list, the acquisitions of new books (in a collaborative capacity when choosing books via the Alice James Award), and the developmental edits of all books.

I also sit on AJB’s Board of Directors, as is the case for some ExDi’s, and I’m responsible for ensuring that the press is running smoothly. I’m also responsible for executing the mission of the press, for ensuring that our mission-driven work upholds the press’s values, and for devising and carrying out strategies for the growth and stability of Alice James.

KARAN

Do you see yourself primarily as a writer who also happens to be a publisher, or do you find that the boundaries between these roles have blurred over time? If so, how do you navigate and reconcile these overlapping identities?

CAREY

If you asked any publisher, I think they would say that reconciling their identities as a writer and a publisher is a fairly complicated and imposing task. What I mean by that is that as publishers, we have a public life in literary art that is very different from the life of someone who identifies in the field solely as a writer. We are often seen as institutions, and oftentimes people will even say things like, “Carey is Alice James.” While, of course, this statement is true to some degree, we can see then how easy it is for our identities to become tangled up with our organizations.

As this happens, I think the entanglement makes it difficult to be a writer in the field, because you’re having to always be both things at once. How do you prioritize?

For me, as well, I find that my loyalty resides first with Alice James and its way of being in the world, so I am careful about my life as a writer; the individuality that I bring as a person to our field were I not the ExDi of AJB, I think would perhaps be different. As I am responsible for the well-being of the organization, though, I have to always consider it in relationship to my own writing and my presence as a poet. There’s not as much separation that can happen between the two identities as one might assume, and even when I’m asked to read my work at various places, I will usually also receive and respond to questions about Alice James.

How this affects my work, I think, is that it makes me extremely vigilant about the quality of the work I produce.

I know we are all very careful to put our best work forward, but for publishers and other writers who work in literary arts, there’s an added layer of consideration.

I read so much incredible poetry at Alice James and we have space to publish just a fraction of that incredible work.

It can be difficult not to have the fact that there’s so much great work out there clouding up my thoughts when I’m writing poems.

Like, sometimes I find myself wondering with all this great writing, how could I possibly have anything more original to say? And how could I get my writing to be “as good” as what I’m reading? In short, perhaps the role also perpetuates an added layer of self-critique or doubt.

It’s taken me some years to resist that, to relax about my poet self and the way that work shows up in the world, and to not worry so much about how that work might affect the way AJB is seen in the world as well.

So, I suppose as far as how I reconcile them, I’d say I reconcile them in that I’ve learned to accept that I’m constantly trying to reconcile them. It’s a process.

KARAN

How do you integrate your personal writing endeavors into your professional role as a publisher at Alice James Books? Are there specific strategies or approaches you employ to balance these dual aspects of your creative and professional life?

CAREY

The way I approach writing ebbs and flows, while my work at AJB remains constant. For years I felt concern over the disparity between the two, the lack of consistency, perhaps.

I wanted to feel as if I was writing “as much” as I was working as a publisher. Somehow that seemed to signify to me, a healthy relationship between the two, that I was always doing both, giving both equal time.

The issue with that way of thinking is that it’s based upon a false dichotomy. While my publishing work takes place between the hours of 9-4, M-F, my writing life (and most writing lives unless you’re extremely lucky) does not take this form.

In trying to achieve balance based on the factor of time alone, I was setting myself up for self-criticism and developing negative thought patterns about myself as a writer, simply because I wasn’t “able” to devote as much time or regularity to writing as I was to my publishing work. I’ve since grown to understand myself better, to be more gentle. Everyone approaches writing differently and there’s no “right way” to be an artist.

Reminding myself of this was helpful in releasing a lot of the pressure I’d placed on myself to produce work and it helped me understand that balance isn’t always 50/50, it’s whatever works for you.

KARAN

What are some of the most valuable insights or lessons you've learned from your extensive experience as a publishing professional?

CAREY

I’ve learned so much, wow, where do I start? What comes to mind first is the value of community. Small press publishing, small press poetry, poetry, these are fields within fields. Niches within niches.

We feel, sometimes, like a vast community. We talk about our expansion, the growth of venues and opportunities in the field, all of which are fantastic things. However, compared to other art forms, we are relatively small, so treating each other with trust, respect, and dignity is something I’ve come to find I value very highly in my work.

I think we are at our best when we’re supporting one another in our efforts, sharing our ideas and strategies, elevating each other.

I also think we’re at our best when we’re giving each other the benefit of the doubt and recognizing that we are, as we are poets and writers, human beings.

We all have our limitations, our passions, our sensitivities, and we use those qualities to draw each other closer, not as mechanisms for tearing us apart or tearing people down.

What I like about poets and writers is that we are, inherently, expansive and flexible in our thinking. We are hardwired to find commonality, and to trust the bridge between two, seemingly, disparate things — hence our obsession with metaphor, for instance. The best work we do is rooted in when we’re transparent and trusting with each other, not seeking ways to undermine or be suspicious of each other or our supporting organizations.

I also learned that while things may appear strong, every institution has their individual struggles and/or potential breaking points. Look at what recently happened with SPD, how they shut down with no warning. Here we had a storied institution that small presses leaned on heavily for support in order to achieve financial stability, sustain growth, and fulfill their missions. Overnight, that stability was ripped from beneath their feet. It was a shock, though moreover, I wonder about whether or not the demise was a surprise.

Or, perhaps, should it surprise us to learn that a prominent literary nonprofit could be this close to going under? It’s a question I think we need to grapple with more as a community.

Are we doing enough to support each other and our institutions, or are we taking for granted that the bedrock of literary arts in this country will always be there (firm ground beneath our feet), while at the same time, we ask more and more of them?

What I’m saying is there’s only so much we can do with as many resources as we’re given.

As individual artists and stewards of art, we must remain mindful and cognizant of the health of our literary ecosystem.

We have to caretake our institutions the same way we/they caretake our writers. Sure, no one will ever do it perfectly or exactly the way we, as individuals, might want them to, but that’s not the point. The point is longevity and preservation, the thriving of the art, the lasting of it after we’re long dead. We have to work together and cooperate, and that is a constant learning process, a day-to-day commitment.

KARAN

You've been a part of Alice James Books for nearly two decades, dedicated to “broadening the spectrum of the American poetic voice.” Can you elaborate on the significance of this mission and how it guides the publishing decisions and initiatives at AJB?

CAREY

Absolutely, and thank you so much for this question. I take the responsibility I’ve been assigned at Alice James very seriously. I know each editor approaches their curatorial work differently. We all have our lens with which we use to focus our vision on the art before us. We also all have our individual aesthetics and beliefs about what makes “good” art.

At Alice James, I see my role, primarily, as a facilitator. As much as possible, I try to refrain from making decisions that reflect me, Carey Salerno, which I think would ultimately be boring and egotistical, not to mention repetitive.

I’m just one person with a set of identities that could never begin to reflect American letters as a whole, so why put myself at the center of our curatorial process?

Instead, I try to remain flexible in my thinking and humble and collaborative in my approach to the landscape of poetry.

It’s true I’m considered an expert, but I’ll always only know what I know right now, and I want to always be comfortable with learning, changing, growing, and engaging in the act of discovery.

And I don’t mean the act of discovery in terms of “finding” “new” voices that have already existed but have been underrepresented, but discovering the resonance of these voices in myself and understanding what that might mean for poetry readers.

I’m most energized when I come upon work written like I’ve never read it or a subject matter treated like I’ve never encountered it. These are the things that ignite our passions, contribute to the broadening of our poetic landscape, and enrich our artistic field.

I’m out for that lifeblood, not just for myself but for everyone. As a public servant dedicated to serving AJB’s mission, it can never be just about me.

KARAN

I just saw that Alice James Books has a translation series, although it's currently not accepting submissions. Could you share the origins of this idea and explain why you believe it's important for poetry in translation to be read and reach a wider audience?

CAREY

Of course, I’ll be happy to. The inception of the translation series is rooted in AJB’s mission. When we considered the landscape of poetry and what gets read by American and/or primarily English-reading readers, we thought we could make a meaningful contribution to the existing landscape by publishing poetry in translation. As we’re well aware, translated work isn’t received in the same way here as it is in other parts of the world. There are some venues that support and celebrate it and there are awards for it, yes, but these opportunities are far fewer than those available for books written predominantly in English.

Reading work by US-based authors can broaden our understanding of poetry, and so, too can reading translated literature. It has its place in our community’s conversations, and its inclusion in our landscape increases the scope of poetry available to the public as well.

Translated literature opens doors to the lived experiences of individuals living in other countries, experiencing social, political, and artistic structures that have the potential to be far different from our own or to, perhaps, call us home.

Reading translated work, especially by our contemporaries, broadens our horizons and engages us to think on a different register. We consider the way in which poets of wider backgrounds utilize poetic devices, for instance. Or, we come to see what kinds of subject matters are prevalent or of interest to readers in other areas of the world. What are the concerns of these poets and their readerships, and how does knowing the answer to that question affect how we see poetry and its function as national and global communities?

There’s such deep care that translators take in bringing this work into another language, and that’s something to be celebrated as well.

The more poetry we have available to us, the better poets we are, and the better stewards of poetry we become.

KARAN

We think a lot about MFA programs and have asked almost everyone we interview for the Substack their opinion on them. Do you think MFAs adequately prepare students for roles in the publishing industry? What are some of the strengths and limitations you perceive in the current MFA landscape in relation to the publishing field?

CAREY

Many MFA programs are doing more and more to assist writers in this area. We need to be mindful that the evolution of educational curriculum and programming can be pretty slow.

I’m heartened by the advances MFA programs have made over the past few years in particular, but it concerns me how some programs still aren’t even teaching the basics about how to work with an editor or submit your work to a publisher, for instance.

Writers really need to understand the fundamentals of the publishing industry. They should be exposed to editors from across the field. They should be learning how to craft proposals, query letters, and how to read and understand basic book contracts.

There’s a lot that goes into a career as a writer beyond writing, and I think the time to be precious about “being a writer” is so over.

Once upon a time, writers could just dedicate themselves to their art, but think about who those people were, what their background was, what they represented. As the field has broadened and become more egalitarian, we have to leave, too, the old ways of thinking behind.

Not everyone comes to the page with the same privileges and advantages as others. So, writers need to be educated about how to advocate for themselves. They need to understand the industry they’re entering. They need to learn about the various ways one can be successful. Once they have the knowledge, they can, to some extent, decide for themselves how they want to show up in the literary world.

Without the knowledge of the choices, however, everything is cloaked in mystery. There’s uncertainty, fumbling, and that’s how people become vulnerable. They can be more easily taken advantage of.

Writers don’t know what they don’t know. They can be scared to ask their publishers questions, because they weren’t taught to ask or what to ask.

Yes, it’s important not to focus solely on getting published when you’re getting your degree. We don’t want people writing poems just to see them published, because where is the heart in that? But the schools of thought aren’t mutually exclusive, and for a long time they’ve been treated as such.

We have to dare to risk teaching writers about publishing without worrying the craft will somehow suffer.

MFA students are adults, and they need to be able to make choices, artistically, strategically, fiscally, etc.

KARAN

Building on that question, do you think an MFA ups your odds for getting your first book published? What factors do publishers consider when evaluating debut manuscripts?

CAREY

No. I don’t think it does, or maybe from my editorial perspective, it doesn’t. Perhaps others feel differently. You’re asking a question about the field, so I should try to answer it, but I also don’t know that I can speak for other editors and their preferences in such a specific way.

What I can say is that a good book of poems is a good book of poems no matter what kind of education the writer of that book may have had.

I mean, as the most basic example, consider the work of all the writers who composed beautiful books before the MFA even existed! Is every poetry book put together before 1940 garbage? No.

Having an MFA can assist you in understanding poetry, your own poems in particular. It can help you develop good reading, writing, and study habits that all contribute to being a successful writer. It also helps you develop your critical thinking skills toward your own and others' poems. These are all incredibly important, but at the end of the day when it’s just the poet and the page, it’s either coming together or it’s not. A degree can’t sway that.

At AJB, we don’t look at a writer’s credentials before deciding whether or not to publish their book. We even ask, for our Alice James Award, that authors strip all acknowledgments from the submitted manuscript.

We want the poems as pure as possible. That’s what the work is about.

Are the poems engaging us as readers? Are they transforming us? It isn’t looking at a manuscript and saying, well these folks went to Iowa and the poems in the book have been placed, so they must be onto something. That’s just following someone else’s lead. It’s actually kind of an unprofessional way to do the work the more I’m thinking about it, because when you make a decision based on those factors, you’re not actually contributing critically to that decision yourself. You’re not thinking about the work and what it’s doing, but you’re just seeing it for what everyone else has judged it for.

KARAN

The Alice James Award is now open for submissions. Could you outline the selection process for this award and explain why it was designed in this particular manner? Do you ever wonder about new or innovative ways to overhaul the first book award at large?

CAREY

Absolutely, yes, the Alice James Award is often considered by many to be a first book award, while it’s actually open to any US-based poet at any stage of their career. Because of the nature of contests and who they typically attract, however, we do end up publishing a large number of first books through this opportunity.

We’ve definitely overhauled it over the years as well. It was formerly the Beatrice Hawley Award, and we updated that to the Alice James Award when we consolidated the submission opportunities the press was offering to poets. At that same time, we were revising the structure of the press, separating the cooperative board into two boards: editorial and one of directors, which allowed each team to focus, more intently, on the work before them.

While we changed the structure of the editorial board, that meant we changed the way in which people came onto that board as well. It was no longer the case that folks joined the board as an obligatory service in exchange for AJB publishing their book, but a service opportunity open to the field at large.

This allowed us to better represent the poets who submit to AJB and the readers who read AJB books, while maintaining the unique mechanism that AJB is known for: its collaborative decision-making process.

The editorial board decides which books to publish from the AJA series together as a group. We come together as a group to discuss 25-30 books, many of which are named finalists, each year after screening all of the manuscripts together.

Of note, each book submitted to the AJA is read by at least one board member, which means it is read by someone who participates in making the final decision about what AJB will publish.

I don’t know if many other presses operate like this, but it’s one of the elements of the work we do that I find is incredibly important to our identity and AJB’s way of being in the world.

As far as overhauling contests on the whole, or the way of doing them, I think the answer to that is money.

The reading fees that presses request help to fund the administration of the programming, the reading work, and the publication of the book that ends up chosen. In order to alter the structure, there would need to be the financial freedom to do so.

It’s hard to see that happening when so many organizations are scrambling annually to make budget or sleeping with their pencils under their pillows at night in hopes of manifesting in that next big grant.

.png)

.png)

%201.png)

.png)